Last April, I collaborated with Élise Lafontaine on her exhibition "Dornach Pillars", at Centre Clark in her hometown Montreal, Canada. I was willing to meet up again to take a reflective, perhaps already nostalgic look back at the exhibition. In the course of our discussion, Élise Lafontaine evoked her relationship to painting, from its technique, its history and the representatives that touch her personally, to the very object, in volume, of painting. She spoke about her investigations, proprioception and spatiality, the inner sound of organ pipes, about the architectures that confine her personal memories but also about her almost visceral need to disorientate and to disorientate herself. We took a stroll around the exhibition, through her paintings and current thoughts, and delve into her work, right to the back side of her canvas, or around.

Marie DuPasquier: Last spring, in May, your solo show at the Centre Clark in Montreal "Dornach Pillars" came to an end. I'd like to come back to this exhibition as an opening to our interview. Could you describe the exhibition in the form of a stroll ?

Élise Lafontaine: Two column-paintings almost two meters tall, installed on bases of different heights, tower over us at the entrance. They make us think of caryatids, liberated from their role as architectural support, resting after bearing the weight of their history for millennia. Thus unburdened, the column-paintings act as presences. Are they guardians of space? They invite us to move around them, lending flexibility to the space. These 360-degree paintings evoke weightless female forms dancing together; another column, at the far end of the room, brings us back to earth with a sensual touch. The color blue predominates, and the visual language suggests the idea that the figures make sense without making history. Four volumetric paintings are arranged on the walls; their pictorial spaces emphasize the presence of the body by a juxtaposition of forms that refer to pipe organs and silhouettes of buildings. A large canvas with a stitched insert and walnut frame echoes a small wooden sculpture hanging high up at the back of the room. It’s an ear-shaped handle. A keyhole indicates that it has another side – that something is hidden from us. All of these metaphoric objects express an interest in the notion of transition between interior and exterior. We're in the middle.

"Dornach Pillars," Exhibition View at Centre CLARK, 2023, © Élise Lafontaine, Photo © Alignements

"Dornach Pillars," Exhibition View at Centre CLARK, 2023, © Élise Lafontaine, Photo © Alignements

MDP: Your works are all meticulously crafted and although they are interlinked, each one carries its unique story. Could you describe one of the exhibited pieces in more detail?

EL: During my visit to the Goetheanum, I had a chance to explore within the pipe organ, a monumental furnishing and powerful musical instrument that was integrated into the building’s architecture. One can pass through it by slipping between the pipes. It reminded me of the first aesthetic experience of my childhood, when my sister and I were singing in church. Our brother was accompanying us on the organ. Perched on the rood screen, surrounded by sculptures, paintings, stained glass, and music, we formed a kind of monument to sensations. When I come into contact with a chosen place, a part of me seeks to reconnect with this type of sound and physical experience and of course with a certain distance with my childhood memories. In "Jeux de fond (The flutes)", I try to reinterpret, in an abstract language and through the energy of colors, the vibrations of the sound that runs through the body. The cylinders represent organ pipes, in tribute to my sister, my brother, and I as a trio.

The volume was created in wood with a CNC router and mounted in a stretcher with rounded sides, made by Frédéric Chabot. I then “maroufle” (glued) linen on all the surfaces and painted on it. This small minimalist piece is both structural and diaphanous, with its gradation of warm colors. In the exhibition, it is a symbol for a pause, a breath, as in a musical score.

Jeux de fond ( The flutes), 2023, 50,80 x 55 x 8,89 cm, oil on linen mounted on volumetric wood, © Élise Lafontaine, Photo © Document original

Jeux de fond ( The flutes), 2023, 50,80 x 55 x 8,89 cm, oil on linen mounted on volumetric wood, © Élise Lafontaine, Photo © Document original

MDP: What was your starting point for this exhibition? As you've been working in a very methodical way for some years now, could you tell me about the starting point of your painting, or as you sometimes call it the "pretext"?

EL: During a residency in Basel, Switzerland at Fondation Christoph Merian in 2022, I visited the Geotheanum, a work of expressionist architecture near the city, several times. A citadel-like structure, it was built in the 1920s and is still home to the Anthroposophical Society founded by the philosopher Rudolf Steiner. I was fascinated by this place, designed according to the principle of lived experience of space, with its metamorphosed plastic forms drawing on metaphysics. Steiner’s project symbolizes a period in art and design that stands outside the established chronologies of Modernism and was highly influential for early abstract painters, including a number of women, such as Hilma af Klint, Maria Strakosch-Giesler et Edith Maryon.

Back at the studio, I needed to distance myself from the Goetheanum, whose dogmatic side I'd quickly come to know. On the other hand, what stayed with me throughout the process was the idea of pushing the limits of my medium even further and taking risks – that is, taking up the challenge of painting directly on a 3D object to suggest the close relationship between painter and architect. In this sense, the profusion of art forms found at the Goetheanum gave me the idea of making an installation of paintings. This is nothing new, but for me it was new to consider reality outside the frame.

Above: © Brian Buchard, Goetheanum, Basel, Switzerland / Below: South staircase Goetheanum building. The lasure technique and the gradual transition from warm to cool colors create an impression of transparency. The anthoposophist painters of the 80s, including Fritz Fuchs, chose this technique to give the illusion that the walls breathe. © Courtesy of Élise Lafontaine, 2022. Goetheanum, Basel, Switzerland

Above: © Brian Buchard, Goetheanum, Basel, Switzerland / Below: South staircase Goetheanum building. The lasure technique and the gradual transition from warm to cool colors create an impression of transparency. The anthoposophist painters of the 80s, including Fritz Fuchs, chose this technique to give the illusion that the walls breathe. © Courtesy of Élise Lafontaine, 2022. Goetheanum, Basel, Switzerland

MDP: When did you first become interested in these sites, and how did you develop your practice of interlacing in-depth investigation of singular places and their spatiality with that of painting?

EL: In 2015, when I was completing my master’s degree, I deliberately stopped painting. I was willing to abandon art to study psychology. So, I tried to design projects closer to communities, especially marginalized communities; imagination in detention situations interested me. On a volunteer basis, I offered art workshops in prisons for women, went to meet with nuns in cloisters, explored the caves in France, and participated in a residency in a psychiatric hospital in Switzerland. My method was simple: to experience these places in a spirit of total openness – without knowing what I was really looking for – and document my stays through photographs, sound recordings, and writings. Each situation guided me toward the next one very naturally. After two years of fieldwork, I began to paint again with a renewed interest in abstraction and a new sensitivity to my choice of materials and how to apply them to surfaces.

Ear handle, 2023, wood - hand carve (Reproduction of a bronze handle at the Goetheanum) © Élise Lafontaine, Photos © Paul Litherland

Ear handle, 2023, wood - hand carve (Reproduction of a bronze handle at the Goetheanum) © Élise Lafontaine, Photos © Paul Litherland

MDP: How do you approach the places you visit, and how have you developed an “experience of enclosed spaces”? What is your personal relationship with buildings, architecture features and human-made structures?

EL: As a child, I drew aerial plans of the houses of family members. For me, they were like portraits. I was also certain that I would be an architect. So, I was always interested in the dimension of perception, which I see as a structure, and that impels me to metamorphose sensations that can’t be articulated into architectural elements. In my view, the architectural object has unsuspected poetic qualities. I can decompose and recompose it in infinite combinations, and even distort it. It allows me to speak indirectly of the body, which I also perceive as a house. From my own experience, I can say that the body conveys something that is beyond thought, as I recognize this body when a tiny fragment of it is inscribed in my painting – perhaps something that resembles it, a woman’s body.

MDP: The elements you "capture" and "absorb" could be a specific hue, a wall texture, the infiltration of light through a staircase, or perhaps the memory of a sense that you lived back then in the space. How do you choose them and transfer them into the painting? And what is your intention? Is it guided by the desire to convey a sensation of the space, to reconstitute a different place, to recreate a site of your own?

EL: It’s impulsive. If I trace back how places are echoed in my painting, I can see that an element that has symbolic value for me opens new formal possibilities. The indefinite form of my paintings allows me greater poetry and freedom in the treatment of subjects that link feminine confinement and the bursting of the frame.

For example, during each workshop in the prison, we – I was accompanied by artist Karine Sauve - offered a variety of sessions during which we reflected together on the imaginary aspects of situations of imprisonment. Gradually, the participants began to talk about “hole” – the solitary confinement cell. One participant used the colour blue in her painting, and she told us that she had just come out of the “hole,” whose walls were painted blue. The women then observed that when they were alone with themselves, the solitary confinement cell freed them from others’ eyes and became a place for introspection. After that, I began cutting window-like shapes out of my painted canvases to insert painted blue spaces on various fabrics. It was very intuitive, and later I realized that the choice to use sewing was not an insignificant one, as the only paid work done by women incarcerated in Quebec's federal prisons is to sew the underwear of incarcerated men. It's very gendered and degrading.

The Great Tower, 2023 © Élise Lafontaine, Photo: © Paul Litherland

The Great Tower, 2023 © Élise Lafontaine, Photo: © Paul Litherland

MDP: Each of these investigations gives rise to technical or formal additions in your practice...

EL: …In 2019, after visiting the caves in France, I decided to make my own frames. My thought was that viewers have to move in front of the painting, they have to develop the work in their imagination. I also liked the idea that a protuberance or bulge would distort the painted image and add shadows and light effects. The painting would thus change constantly depending on its environment. I did some contour drawings, and they couldn’t be abstract but they also couldn’t be sketches of highly defined objects. I wanted something between the two. At that time, my work benefited from technical advice from collaborations with my studio neighbours, seamstresses (Flyss rembourrage) and a cabinetmaker (Richard Caron).

I remember my first request to the seamstresses was to build a confessional-painting. I wanted to create colorful empty spaces in the painting into which we could project ourselves. The confessional model interested me because it's a dramatized objects, a piece of furniture on the scale of the body, which can become a fictitious place in which to invent a sinful double life. There's also the little grid that lets you see through to the other side, which adds to the disturbing and curious experience. So I started cutting patterns in my painted fabrics to recreate this type of space. As the project was monumental, the seamstresses suggested starting with small prototypes. That's how my first volumes for the Peau(x) de pièces exhibition at the gallery Pangée in Montreal came about.

Around that time, I also discovered the works of Zelia Sánchez, Lygia Clark, and Franz Erhard Walther, and I reconnected with my father’s love of antique furniture. I realized that I had grown up in a house full of richly ornamented wooden objects. Even my bed looked like an oversized casket-boat. So, I transitioned from sewn volumes to volumes in wood.

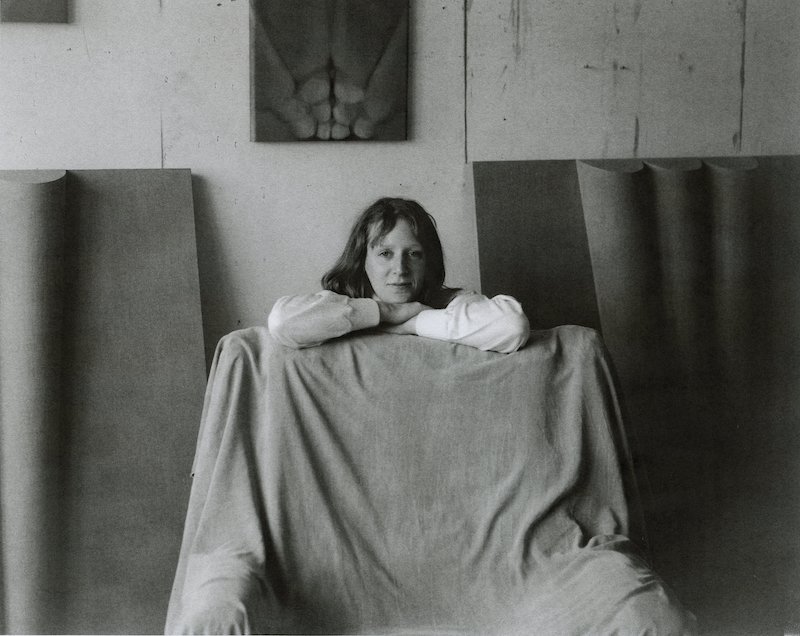

Position II, 2023 © Élise Lafontaine, Photo © Paul Litherland

Position II, 2023 © Élise Lafontaine, Photo © Paul Litherland

MDP: In the process of “transfer”, other elements or other references are added, whether they come from your research, other places, writings, your past or your current situation. What room do you give them and how do they incorporate into your paintings and exhibitions, all the while preserving the idea of place?

EL: The column-paintings pay tribute to pillar-women in my life – to those I’ve known personally, especially my mother, and to pioneering abstract painters, including Hilma af Klint (1862–1944). I was fascinated to learn that Klint and many other women painters had visited or participated in construction of the Goetheanum. Ultimately, each project starts through contact with a place, but in the transfer, I note the importance of paying tribute to the lives of a group of women in my work. That may be why the writings of the mystic Teresa of Ávila have inspired me so much: she uses the metaphor of architecture to speak of elevation of the female body. Many women artists build their thought in terms of a place to live. I’m thinking here of the “woman house,” a recurrent theme in Louise Bourgeois’s work or the “ soft sculpture” of Heidi Bucher

MDP: How did you develop your color palette and the way you work with transparency?

EL: When a figurative image appeared, I tended to rub it out using a cloth soaked in solvent. One day, I didn’t have any clothes, so I decided to sand the surface. I immediately liked the vibrant effect as under-layers of colours were revealed in little shimmers and the contours of shapes were softened. I started to apply fine layers of oil paint on very thick Polish linen and to sand between the layers. The colours vibrate together and sometimes there’s a backlighting effect, as if the painting were illuminated from behind. Also, my palette changes a lot as I go, so working by transparency is practical, because the oil dries quickly. Many people mention bioluminescence to me when they see my palette. I think that speaks to my desire to portray the threshold between the visible and the invisible.

Dornach Pillars, 2023, oil on linen on volumetric wood © Élise Lafontaine / Photo © Paul Litherland

Dornach Pillars, 2023, oil on linen on volumetric wood © Élise Lafontaine / Photo © Paul Litherland

MDP: Can you tell me about the pillars in particular?

EL: On the canvases, abstract figures that evoke caryatids are fluid and in motion. They echo the figures found in the volumetric paintings on the wall: Dornach pillars. Their heads are at the bottom or the top, as if they were dancing with no reference points, no horizon line. The first step in the process was to cover the columns with cotton. I had to move the columns around on a cart, place them on a table, climb a ladder, and turn them upside down to paint their entire surface. I liked to paint by moving around in this way, and especially to paint an infinite image, without limitations or frame. It was a hell of a challenge, but when I think back, my work has always brought me back to the origins of pictorial art, when painting and architecture were closely linked: cave paintings, Etruscan tombs, the vaults of religious monuments.

The funny thing is that some visitors saw shapes that call for sorority, immaterial bodies, inhabited by ghosts and spirits, while others thought they were phallic forms, done with humor, with the aim of criticizing the “male gaze” in abstract painting. I gladly accept all definitions...

MDP: In fact, these paintings in volume, arranged at the center of the space, also create a different apprehension of the exhibition space for visitors. What was the underlying idea behind the arrangement of the works?

EL: During our discussions, you brought up the notion of disorientation, which I felt summed up my research into places, i.e., they made me feel time shifted, suspended. So I sought to recreate this feeling of disorientation for visitors by proposing pictorial works that don't present themselves head-on, and that make us move around in a different way. I've seen visitors put their heads against the wall to see if the painting continued to the back, and others turn around the columns in different directions. The proportions of the works were perfect for the space, and this is thanks to the fact that my studio is similar in size to the small room at the Clark Centre.

A photo from Élise Lafontaine's last visit to the Goetheanum, which I visited several times during my residency at Atelier Mondial in Basel. Here, a huge stained glass window, cut and colored red, overlooks me and tells the story of man's individual and cosmic development. Courtesy of Élise Lafontaine, 2022. Goetheanum, Basel, Switzerland

A photo from Élise Lafontaine's last visit to the Goetheanum, which I visited several times during my residency at Atelier Mondial in Basel. Here, a huge stained glass window, cut and colored red, overlooks me and tells the story of man's individual and cosmic development. Courtesy of Élise Lafontaine, 2022. Goetheanum, Basel, Switzerland

MDP: Once you're in your studio, you paint your canvases upside down – or you paint them right-side up, but turn them upside down to exhibit them. There's a kind of desire to disorientate yourself, a disorientation that is perhaps not perceived but experienced by visitors... Is this something you're looking for?

EL: As far back as I can remember, I've always turned my canvases in all directions, as many painters do, so as to reconsider the balance of forms and gain a certain distance, but for me it's all about escaping the known. It's my strategy to disorientate myself and remain open to other spaces, those I wouldn't have been able to paint on purpose. I also reverse the photographs of the places I'm documenting. For example, when I flipped the images of the vaults of the cathedrals I visited, the lines suddenly drew silhouettes of women with open arms. In this way, the architectures take on a more anthropomorphic direction when turned upside down. The idea came to me thanks to the image of the hanging man card in the ancient tarot, which signifies being on hold while seeing things in reverse. A man hanged by one foot and his hands tied cannot act. This sense of floating allows us to take a fresh look at our environment through the involvement of the body. I hope visitors feel this ambiguity, this multiplicity. These spaces offer us a kind of upside-down figuration, which leads our gaze to prevent us from seeing something precisely, but rather to feel it.

MDP: What are your next exhibitions ? Do you already know what direction will take your work?

EL: I'm taking part in group shows, one in London organized by curator Thom Oosterhof in partnership with Candid House Projects, at Livart (Montreal), curated by Anaïs Castro and Alice Ricciardi and ArtToronto fair with Pangée. For these projects, I'm concentrating more on the dialogue between relief and painting. At the same time, I'm doing research for my solo show at Pangée (Montreal) in spring 2024.

MDP: What's the next step in your research?

EL: At the moment, I feel the need to exaggerate shapes. My shapes are always constrained or cramped in the painting. I'd like "corporeal" forms to be able to go to the end of their gesture, of what they have to say or carry. At the moment I'm making sketches and collages from my archives, which allows me to break away from an overly systemic approach to research.