Portrait Sophie Erlund in her studio / photo: Anna-Lena Werner

Portrait Sophie Erlund in her studio / photo: Anna-Lena Werner

There is always something unrecognizable – a small moment of disturbance and hesitation – in the work of Sophie Erlund, a Danish born artist living and working in Berlin. Trained as a sculptor during her BA at London’s Central St. Martins College, as well as in Copenhagen and Rhode Island in the US, she dedicates her practice to creating sculptures, installations and soundscapes and to exploring questions about the more-than-human. Starting her career in Berlin with legendary self-organized group exhibitions in her apartment, titled “HOMEWORK”, she has since exhibited internationally in galleries and museums.

It’s early spring 2023 – Sophie and I are now sitting in her studio in Kreuzberg, located inside a large industrial backyard building where lots of artist friends and Sophie’s partner also have their workspaces. Her dog Ayla joins us, we drink strong coffee. We’re surrounded by singular works of hers that were once part of an exhibition she did or currently in preparation for upcoming projects. I am resting my eyes on a wood structure that is placed on a table just next to us and seems to be in progress of becoming something else. Again, I can’t figure it out, but it looks like one of Sophie’s pieces. Both organic and architectural, no recognizable shape and still familiar. I ask her about its history and she shows me a photo of a similar work, once integrated in an exhibition called “Lived synchronicity” at PSM Gallery in Berlin in 2018. That’s how our interview begins.

Above: "Human motion", 2018, Photo: Nick Ash. Below: "Human motion", 2018 (detail), Photo: Erik Tschernow. Both courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

Above: "Human motion", 2018, Photo: Nick Ash. Below: "Human motion", 2018 (detail), Photo: Erik Tschernow. Both courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

ALW: What was that exhibition “Lived synchronicity” about?

SE: ‘Lived synchronicity’ was a show about reverberation and about how images travel. Reverberation relates to sound traveling and coming back at you. This traveling can cause distortions and frictions. I think images can do the same. The installation included projections, moving images and animation projections, referring to objects you'd see in the different rooms in the exhibition. It was impossible to see the full installation from any one place in the space. I wanted to create layered information, and play on how it is digested, like an echo. A conveyor belt was moving and had drawn images on leather, while a narrator read a text about reverberation by Russian philosopher Eugene Minkowski, that I had cut up in a way that resembled distortions of sound. The narrator’s voice was the same androgynous voice that I've used in all my sound pieces – even in the VR piece.

"Lived Synchronicity", 2018, Photo: Nick Ash. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

"Lived Synchronicity", 2018, Photo: Nick Ash. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

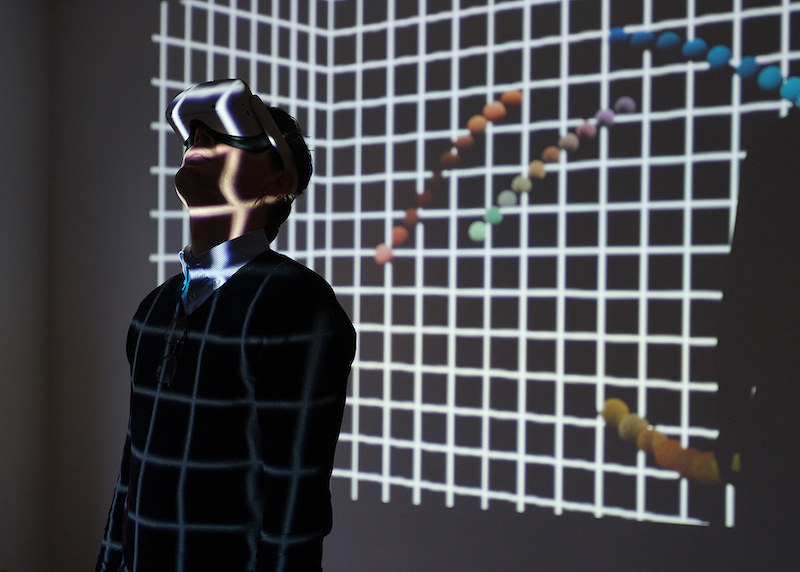

ALW: You are referring to the center piece of your last exhibition “Nature is an event that never stops”, at PSM Gallery in Berlin, where you exhibited a 20-minute VR film that guides visitors through different worlds. This work addresses how cultural transmission and conditioning affect perception and individual decision making, especially based on a range of colors that participants have to determine and match. I suppose the subjects of reverberation and distortion play strongly into it, too. Can you tell me about how this project evolved?

SE: The VR piece came about as an art-science-collaboration, because it addresses one of the research questions from the EER Group – Experimenting, Experiencing, Reflecting, a collaborative project about science and art led by Olafur Eliasson and scientist Andreas Roepstorff. In the beginning I assisted Olafur Elliasson’s position in the group, for whose studio I work, but later I joined the group as an artist myself and brought in my own artistic ideas, next to managing and directing the group’s various projects. The project has three major research questions: the first has to do with identity and who we are in the world when we do things together. The second research question has to do with participation under conditions of uncertainty. And the third regards cultural transmission and learning from what we do in the world. Within this group of artists and scientist, we had started talking about color perception, planning an artwork, investigating perceptive mechanics through color matching experiments and incorporating a more than human perspective. We created a rough and plain setup for the experiments inside the VR space, and I was very keen to develop an interactive work studying the perceptive mechanics and transmission chains in their purest form. I began planning the VR work into a setup that would resemble a computer game with a succession of different worlds, where you would encounter interactive color perception experiments and a narrator would be talking you through some of the philosophical questions underpinning this project. I told the programmer, Daniel, about the possible difficulties realizing the VR work, but he literally said: “Anything is possible in VR.”

"Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, Photo: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

"Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, Photo: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

ALW: What do participants experience once they are inside the work?

SE: You begin in a world that is set in the city, in human scale, then continue into a grass world, where you're a tiny insect. You go into the crust of the earth, where you become a particle – a part of this mycelial web. From there, you get shot out into outer space, you're defying gravity, you're a piece of space junk floating around. From there you are moved into the meta space – a philosophical space where the narrator poses questions: Who are we? Are your agencies educated? Are they working to your benefit? How aware are you of the things that you're doing in the world? In each space participants are asked to do color matches, thus exploring cultural layers, for example when matching a blue sky. This a very individual match, based only on your understanding of blue. In the end of the VR work you move into the control center, where you see all the color chains, and the narrator tells you “look, you're part of this, you've changed this world, your contribution is in here, and it has an effect”. By that I mean a direct effect on the next person coming.

Above: "Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, universe scene still / Middle: "Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, earth’s crust scene still / Below: "Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, meta space scene still, all courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

Above: "Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, universe scene still / Middle: "Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, earth’s crust scene still / Below: "Nature is an event that never stops", 2023, meta space scene still, all courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

ALW: As a trained sculptor, I wonder how you incorporated your object-based perspective into the VR work?

SE: Two years prior to that show, I had done a piece with ceramic objects and a video. It was an installation called “Parliament of Entities”, addressing the ecological crisis, considering non-human friends – a parliament of non-human entities. Ceramic objects are the actors in the video. My assistant Marie, who is an artist herself, suggested animating the objects for the video. I hired her to do the animations. This is how the language you see in the VR work started.

"Parliament of entities", 2021, Photo: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

"Parliament of entities", 2021, Photo: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

ALW: Your practice always involves tactile and sculptural artistic techniques, as well as digital, auditive or lens-based work. Do they always relate to reach other? How do they reverberate, to stick to the terminology?

SE: They might come across as being quite different, because materials have very strong visual indicators. As an artist, you can't really escape your own language. And it's also something that you spent quite some time on building up. When I start something new, I can always ‘feel’ the piece – the core is clear from the beginning. When I'm unsure how to realize an idea, I just start making sculpture – that's what I studied, it's maybe my strongest language. When I make sound or even the VR work, I think around the same parameters as when I'm building a sculptural structure – it's the same kind of thinking, a space of thickness, of texture, the same language.

ALW: The title of the VR-work and the exhibition “Nature is an event that never stops”, also poses the question of what we define as nature and us inside of it. Is nature an ecological system? Are we nature? Do we count AI models as nature, because we made them? People are on the verge of making decisions, whether they are in skeptical opposition to artificial intelligence, or whether they see it naturally becoming part of our language and life and bodies. Where do you position yourself in this discourse?

SE: I think I'm definitely on the skeptical side. And the more I deal with it and speak with people who work actively in the field of it, I'm realizing that even if you are a skeptic, taking distance is really difficult, because artificial intelligence is already everywhere. We've already set up systems affecting us as humans. AI is becoming more integrated in all frameworks of our society’s structure. We are obsessed with progress – we think that we more intelligent than nature. And we keep designing systems that come from our logic. All this is infiltrated by capitalistic structures, even if one wants to be anti-capitalistic, we participate in capitalistic structures via the algorithms. The way that we design, value and decide things, is always encouraging productivity. A previous exhibition of mine was called “Destined to protect the productive”. I'm not sure we know how to find ways of being and thinking against it. AI systems are offering us higher productivity on various levels. And we submit to them all the time. It's a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the AI world, they talk a lot about the next billion users – the ones that will lift the force of AI to be integrated in all structures. And these next one billion users are in the Global South, giving people access to a world that they never had access to. I think this will be quite impossible to turn around. That means, some of the class and power structures that have been controlled by the Global North could be breaking down. I’m curious to see what it's going to mean for the future.

ALW: “Nature is an event that never stops” involved a weekend of discursive events at PSM Gallery with scientist from the EER research group. In one of the panels, you jointly addressed the question “What is the memory of the future?” Can you relate to that question from your artistic practice?

SE: This question is one of the main subjects from Helene Nymann, another artist within our research group. I talk a lot with her about it. A memory of the future might hold the opportunity for you to think differently, if you can be compassionate towards it. To me, this thought is interesting when I think historically. When I moved from Denmark to Berlin, I used to be quite fascinated with communism and the GDR, and with the people’s nostalgia towards the feeling of believing in the ideal society of the future. That ideal was on the horizon, because it wasn't there yet. They were still building on that ideal. A memory of the future is something that you're anchoring in hope, something that may contain empathy as well. That's why I'm interested in the human in the digital age. I think it's a really strange moment that we're in right now – amidst an ecological and a humanitarian crisis. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing wrote a book called “The mushroom at the end of the world”, in which she drafts a kind of philosophy of how the neural networks of a specific mushroom, called the ‘matsutake’, could be a model for a future society. This is interesting, humans suddenly went from not just tool makers, to getting an automation built in which might move things at triple speed – it might change who we are, our societies, maybe even the dynamics of power.

Studio view Sophie Erlund, 2023 / Photo: Anna-Lena Werner

Studio view Sophie Erlund, 2023 / Photo: Anna-Lena Werner

ALW: What about your sculptural series “Core Sample from the Technosphere” (2021)? The objects reference the shape of samples taken from ground drillings for geological research, a method to visualize and thoroughly analyze the geological layers from the last thousands of years, identifying past natural and social occurrences, such as storms, floods or even wars. As your objects were imaginative and made of concrete, pigment and many small objects that you placed inside of them, I wonder if they are future memories to you?

SE: I should have thought of that, but I didn't actually intend for them to be like that. Once they were finished, I could see them as a memory of the future. A core sample from now, a projection of something that will be. A meter-long core sample would show us layers from as long as a million years ago, rendering my ‘Core samples from the Technosphere’ would be a memory of our time, the technological age, in the far future! These sculptures do not project anything negative – they are not grey, but they do promise an uncanny uncertainty, as you encounter them and not knowing what they are. To me they are layers of time and our livelihood together. They are cast in a rubber mould, in which I poured and layered mixes of concrete and different colored pigments as well as objects. It was both, really fun and really hard to make. It takes a whole day to build one object, and then you can't see it until the next day when the concrete is set, and you take the mould apart – a completely magical way of working. I have a failed one standing here in the corner of my studio. It’s heavier than the other ones and at the very top, it has this thin glass object. When you lift it, the glass is right by your neck. It's so scary. I can't even touch it. It's just sitting there. But I don't want to throw it out either. It's nice to have it around.

Above: "Core sample from the technosphere I-VII", 2021, Photo: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza / Below: "Core sample from the technosphere III", 2021, Photo: Erik Tschernow / both Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

Above: "Core sample from the technosphere I-VII", 2021, Photo: Marjorie Brunet-Plaza / Below: "Core sample from the technosphere III", 2021, Photo: Erik Tschernow / both Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

ALW: A subject that reoccurs within your practice is the notion of an ‘irrational mind’. Can you elaborate on that a bit?

SE: At one point, most artists question the function of art, producing things to be in the world that don't really serve a specific purpose, or what is that rational purpose is then the question. If I am in that crisis, I think of art as related to philosophy, encouraging abstract thinking. Abstract thinking is related to the irrational mind. We use and train our rational mind all the time, through schooling and conditioning. But I would like to encourage that we have a certain compassion for our irrational knowledge. I think that art language is anchored in that. We have been unconditioned to nurture the irrational, but it's connected to creativity. The uncertainty is necessary to allow unique moments to happen. There are many nuances in abstract thinking, which is what also mathematicians and scientists use to find original new material. I like a world where not all things are about convergence and probability.

ALW: Since when have the subjects of psychology and the conditions of the human mind affected your practice?

SE: It wasn't until I was pregnant in 2006. I had a real artistic crisis. I was young and didn't really know how to deal with the situation. I stopped making art. And my studio just turned into a dusty landscape of nothingness. I was suddenly introduced as the “pregnant wife”, and felt a total crisis around me as an artist. Right before I had stopped making art, I found this table, which was really only a set of table legs, very ornamented and quite ugly actually. Back then I worked a lot with found objects. I kept this table in my studio and then at the very end of my pregnancy, after months on end of not being able to make art, I woke up one morning and wrote a letter to my unborn daughter – beginning with “dear baby girl”. In the letter I explained that whole feeling of being unsure about whether I could make art again, and that I was excited to see her. In that moment I had my first new idea in a long time. I drew my idea of those table legs and kind of a glass cube on top of the legs.

After a while I met Sabine Schmidt – she had a project space back then and wanted to visit me in the studio. I didn’t know what I was going to show her, I just dusted everything off and then put out this drawing, because it was the only newer thing I had. I had the table legs, the drawing and then this letter. Based on that work she said: “I want to represent you. I'm opening a gallery.” She helped me conceptualize my work and was, actually until today, very encouraging. For my first exhibition at Sabine’s gallery, PSM, I turned “Dear Baby Girl” into a sound work, and the table legs became my first ‘house sculpture’. I called it “Domestic brainscape” (2009). The house was a symbol of the body and of emotional states. I made a lot of objects that I called ‘houses’, although they were body size. They are more of a shell, the human as architecture.

"Domestic Brainscape", 2009, Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

"Domestic Brainscape", 2009, Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul. Courtesy of the artist and PSM, Berlin.

ALW: Now that you are referring to the idea of the body as a house, and when I think again about the work “Lived Synchronicity”, I realize that I often thought of your work connected to architecture…

SE: …When I went to art school, I invested a lot of energy into researching about the difference between sculpture and installation. I moved to Berlin after my graduation, beginning to work with the city’s histories and telling these stories through fictive characters. I would make these installations that were like someone's room. All the things in the space were saying something about the person's history, as if that imagined person was still there. My first solo show in Berlin was called “Newa”, and it took place at Program on Invalidenstraße – Carson Chan and Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga had founded it as a space for art and architectural collaborations. I worked with the history of the building which housed Program, and created installations made of found and built objects. There was a sound piece in the show, for which I had recorded a woman called Renate Bronnen, a former well-known actress, who was once an honorary citizen of the GDR. Her husband, Arnolt Bronnen, was a playwright, a friend of Berthold Brecht, and they would frequent the restaurant in this building. Back then it was a hotel called “Newa”, a place where people with special privilege in the GDR would go – people from the communist party, but also artists, actors and playwrights who followed the system. They had access to things like champagne, caviar, nylon stockings and bananas that others didn’t. I had a long interview with her and cut up her story into a kind of staccato poem. That was my strategy for making these installations: setting it around someone's stories or fictive stories.

Studio view Sophie Erlund, 2023 / Photo: Anna-Lena Werner

Studio view Sophie Erlund, 2023 / Photo: Anna-Lena Werner