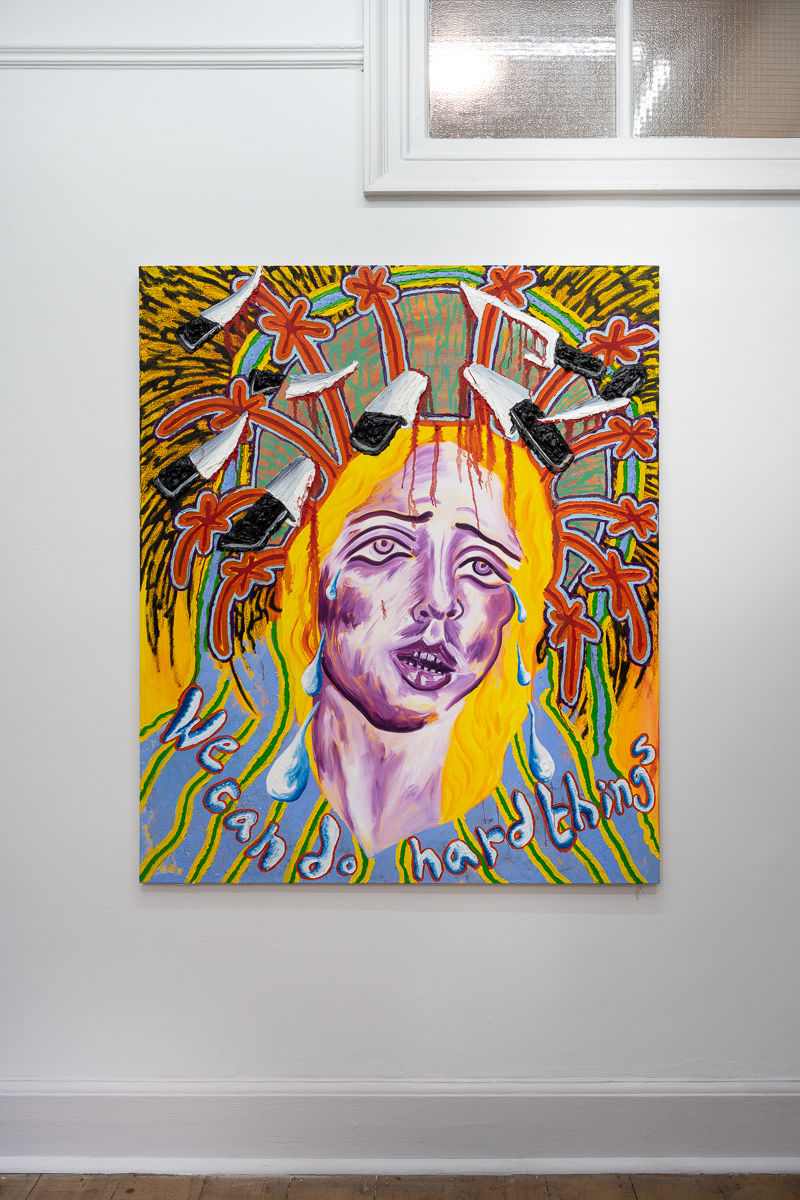

India Nielsen "guardie e ladri (cops and robbers)" - 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths

India Nielsen "guardie e ladri (cops and robbers)" - 2021 - photo © Damian GriffithsIn her paintings, London-based artist India Nielsen interweaves subjective experience with elements of the 1990s and 2000s pop culture. As a teenager, she identified with MTV (Music Television) stars, such as Britney Spears, Madonna and Eminem. At the same time, the visual, ritualistic world of her Catholic upbringing were formative: the saints with their supernatural abilities, seemed to her to reflect aspects of the human psyche split in pieces, the iconography of the Sacred Heart and the Weeping Virgin Mary and the spiritual dimension of Catholicism. India Nielsen sees her paintings as vessels in which her inner life, her memories, feelings and projections can be inscribed and unfold. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Art from 2012 to 2016 and graduated with an MA in Painting from the Royal College of Art in 2018. On the occasion of her London solo presentation “M is for Madonna, M is for Mariah, M is for Mother” at Darren Flook (which also marks the inauguration of his new gallery space, a former psychotherapist’s office on 106 Great Portland St.), we discuss the effects the COVID-19 pandemic had on Nielsen’s practice, her enduring love for pre-eminent pop divas, her fascination with the saints of the Roman Catholic Church and the distinct dichotomies that pervade the artist’s painting practice.

Jürgen Dehm: India, how have you experienced the last months between the lockdowns and taking individual steps back to normality?

India Nielsen: It sounds obvious, but I became very aware of the fact that I am completely out of control of many things in life. This was overwhelming at first, but once I surrendered to that reality, I really began to enjoy it. I went on forest runs, listened to a lot of music, read, made drawings… I also reached out to people more so than I had before the pandemic. I spent a lot of time talking to people on Skype and FaceTime that I previously probably wouldn’t have spoken to. I valued inner and outer connection a lot more and it really showed in my paintings as a result. I was also lucky to still be working, writing, and teaching (via Zoom). And doing shows.

JD: Could you elaborate a little bit more on how your experience of the pandemic showed up in your paintings, in your opinion?

IN: Well, that thing I mentioned before of realising you’re not in control and deciding to surrender to it completely: it freed me up. That’s more of a general mindset – so it makes sense that it would affect my paintings. I have a lot of ideas for work that generate from the process of painting, and many appear to come out of left field. Before the pandemic, I would sometimes do this dance of “God, that’s so cheesy, there’s no way that could work” – so I would do something else instead that did make sense. That would, inevitably not work out and I’d end up going back to that hazy idea I had in the first place. I don’t do that dance anymore. I just do the original thing. I’ve learned to trust my instincts.

India Nielsen "M is for Mmmmmmmm (safe to take a step out)" - 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths and detail photo © India Nielsen

India Nielsen "M is for Mmmmmmmm (safe to take a step out)" - 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths and detail photo © India NielsenJD: The title of your current exhibition at the Darren Flook Gallery is “M is for Madonna, M is for Mariah, M is for Mother.” Why did you choose this title?

IN: It grew naturally out of “Crybaby”, my solo presentation at im labor gallery in Japan in March of this year. I showed a painting in the window space with the same title: “M is for Madonna, M is for Mariah, M is for Mother.” I often make playlists for new cycles of paintings and listen to them as I paint. The repetition of the letter “M” and those names kept bouncing around in my mind until they formed that sentence. They refer specifically to famous icons who featured heavily on the studio playlist, as well as having both universal and archetypal meanings. I like the rhythm of it and the way these names kept bouncing off this very neutral letter “M”.

JD: The names mentioned in the title of the exhibition – all of them female – are ambiguous. They are the names of well-known stars from pop culture: Madonna and Mariah Carey. But they also refer to figures of saints in a Christian context.

IN: You can read them as a direct reference to these female pop stars, but there’s also the virgin mother of Christ who’s often depicted in a state of constant grief. The product of said grief, her tears, has healing powers. Then there is the imperfect but at least real relationship you have with your own mother. That's a sub-reference. There is also the idea that these role models that you adopt as you grow up become a kind of surrogate mother while you develop throughout your life.

India Nielsen "Hey Britney (you say you wanna lose control)" 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths

India Nielsen "Hey Britney (you say you wanna lose control)" 2021 - photo © Damian GriffithsIN: I spent the first six years of my life in my nonna’s (grandmother’s) house, which was full of Roman Catholic saints. Each saint has a very specific meaning or role like St. Dymphna, who is the patron saint of anxiety. And when someone in the family lost something, my mum would always pray to St. Anthony, for example. I remember relating these saints to people like Eminem, the Wu-Tang Clan, the Spice Girls, Britney Spears or Destiny's Child as I got older. This was in the early 2000s, during the MTV generation, when music and music artists were being marketed to kids. For example, Eminem and Dr Dre were going down the comic book route and presenting themselves as superhero characters, dressing up as Batman and Robin in their “Without Me” music video and incorporating slapstick sounds in their beats. Groups like the Spice Girls were also reduced to really basic characteristics – there’s “Baby”, “Sporty”, “Scary”, and so on. Although back then I didn’t think of it in such explicit terms. I had an understanding of these figures as being fragments of one “whole” person who has been split apart. All of those saints I referred to earlier, and there are over 10,000 of them, they all represent different states of being or circumstance but they are all aspects of one person. All of these states exist inside us. That’s how I understood it.

JD: The Sacred Heart is a recurring motif in your works.

IN: The Sacred Heart is iconic – something that I saw all the time as a kid. My nonna would always give me little presents, small plastic-coated prayers that you carry around in your pocket with a miraculous medal inside and sometimes with an image of the Sacred Heart. I remember she gave me one when I started primary school and told me that it was magic and had protective powers. It’s a type of role-play. Having this object that you believe has magic powers and then somehow by being in proximity to it, it gives this power to you.

JD: One male person appears in a painting in the Darren Flook exhibition: Eminem.

IN: Eminem was one of my first role models, when I was just starting secondary school. I’d never experienced anyone to be so many things at once. He had this aggressive energy filtered through an incredible intelligence and sharpness, but at the same time he was a complete fool. He used his command of language to completely degrade himself – which I loved.

Do you remember the rap battle scene in “8 Mile” where he spends his half of the battle just ripping himself apart? That’s how he completely disarmed his opponent. I loved that so much. That felt like the ultimate kind of power. You embrace your vulnerabilities and failures and you own them – that turns them into something powerful. He was probably my first transgressive symbol as a kid, I actually thought he was a real-life version of Dennis the Menace (who I was also obsessed with). I had to put him in the show.

India Nielsen "The Real Slim Shady" - 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths

India Nielsen "The Real Slim Shady" - 2021 - photo © Damian GriffithsJD: Your latest paintings often feature animals: spiders, snakes, butterflies, but also ants. What do you associate with them?

IN: I like that the silhouettes of animal forms have no connection to any specific time period or history. They’re constant. It makes them feel open for me to use these forms as vessels to hold other meanings, like other images or lyrics or text. The ants up until now have always been shown in a specific context: being burned with a magnifying glass, using the sun’s rays. That’s something my dad taught me to do when I was really young and that he himself learned when he was growing up in Australia. Though it was a horrible thing to do, I think I was about 5 years old, it was also an exciting thing to discover that I could have some sort of tangible relationship with the sun – an enormous, mythical, distant being in my mind. On a smaller scale, it was also a bonding experience with my dad… I don’t think I’ll do that with my kids though.

Above "Sacred Heart II (Intimas)" and below "Burning Ants (FEEL IT ALL)", both by India Nielsen - 2021 - photos © Damian Griffiths

Above "Sacred Heart II (Intimas)" and below "Burning Ants (FEEL IT ALL)", both by India Nielsen - 2021 - photos © Damian GriffithsJD: Something that belongs together and is forcibly separated is another motif that appears. Then there is the painting of the capybaras in love, under a rainbow. Is it the tension between attraction and violent separation you are interested in?

IN: This is another thing that carries over from childhood. In other generations, particularly before the Internet, the things that you were into, the music you listened to and the books that you read, etc., would probably be a good indication of the specific, local culture you grew up in. You might have been able to tell where someone was from based on the bands they liked. Growing up with MTV and the Internet, I felt that I had a very intimate, personal relationship with the music and cultural figures I idolised. But I also had a very distinct awareness that we had no actual common ground linking us, you know, it’s all virtual. So, there was this feeling of extreme intimacy, but also of distance. That’s a tension that runs through many of my paintings.

India Nielsen "M is for Mother" - 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths

India Nielsen "M is for Mother" - 2021 - photo © Damian GriffithsJD: In the past, you often used blackletter typeface in your paintings. It evokes a certain aggression and masculinity. For your recent paintings, you made a different decision. What motivated you to do so?

IN: It was a natural decision driven by how I wanted the text to move through these works. In many of my blackletter paintings, the words float in front of or behind elements of the painting. In many of the works at Darren Flook I wanted a kind of type that would allow me to weave it in and out of the different forms and material of the painting. Calligraphic typeface really lends itself to that. For example, in “M is for Mmmmmmmm (safe to take a step out)”, the painting of the two capybaras under a rainbow, the imagery and text are intertwined. Every element of that painting is very tightly weaved together. I don’t think that would have worked with blackletter.

Above "…and words are futile devices (HSEMINIAATI)" and below "The End, The End", both by India Nielsen, 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths

Above "…and words are futile devices (HSEMINIAATI)" and below "The End, The End", both by India Nielsen, 2021 - photo © Damian GriffithsJD: How do the text elements, some of which are reminiscent of a secret code, relate to the other pictorial elements?

IN: I see text and imagery as the same, like brushstrokes. They're just another way to close down meaning and open up others. If I see myself going too far down a certain path while painting, I’ll change course, because I don’t want to sink too far in one direction. I want to feel constantly present. Sometimes, the textual elements are very blunt and a matter of fact, a statement. Other times they are codes or a sigil that I’ve used. They have a personal function and meaning, but it doesn’t matter if you know it, I just want people to feel it.

JD: In the exhibition at Darren Flook, there are large-format pictures in close proximity to very small ones. Why did you decide on these contrasting formats?

IN: Well, for the show I only made those two sizes: small paintings, which are about the size of a tablet or scroll, and then the larger paintings which are about the size of myself – I could almost step into them. I like the feeling you can both step back from and step into the paintings.

Above: Installation view “M is for Madonna, M is for Mariah, M is for Mother” at Darren Flook, and below India Nielsen "In-side / Out-side" - 2021 - photo © Damian Griffiths

Above: Installation view “M is for Madonna, M is for Mariah, M is for Mother” at Darren Flook, and below India Nielsen "In-side / Out-side" - 2021 - photo © Damian GriffithsJD: You also added sculptural components, the so-called modules, to your painting in the past quite often. Why didn’t you use them for the exhibition?

IN: The gallery space at im labor in Japan lent itself to the modular work – there were lots of long, narrow spaces above and between the walls I wanted to make use of. I made the modules specifically for that space. When I first started making the modules a few years ago, they sat on the corners or along the edges of the paintings. For my solo “Crybaby” at im labor I wanted to create more distance between the modules and the paintings. This meant they were still read together, but formed more expanded combinations within the space, like stretched-out Tetris pieces. The space at Darren Flook is totally different and, considering the recent paintings I’ve been making, it made sense to show them alone. In this exhibition I’ve shown mainly small-scale paintings that are very dense, both in terms of the imagery and the material. I decided to install them in the main gallery so there was enough space around them for them to maintain a sense of lightness. They run along the edges of the room like words in a sentence, bouncing off of and punctuating each other without being monotonous. When it comes to my work I don’t want to feel as if I must do something just because I’ve done it before.

Portrait India Nielsen, Photo © Acacia Mei

Portrait India Nielsen, Photo © Acacia Mei

India Nielsen

"M is for Madonna, M is for Mariah, M is for Mother"

until the 20th of Nov 2021 at

Darren Flook Gallery, London

www.indianielsen.com