Marianna Simnett, The Bird Game (film still), 2019. Courtesy: the artist, FVU, the Rothschild Foundation and the Frans Hals Museum

Marianna Simnett, The Bird Game (film still), 2019. Courtesy: the artist, FVU, the Rothschild Foundation and the Frans Hals Museum

In 2018, just after the New Museum in New York, the Museum für Moderne Kunst / MMK Zollamt, in Frankfurt hosted an exhibition that presented Marianna Simnett's immersive five-channel video installation Blood in My Milk (2018). I visited this work more than five times with different friends and colleagues. Rewriting narratives grotesquely, this work of Marianna Simnett stayed with me for months, causing flashbacks to multiple references in the 73-minute film, such as its sensual and often shocking images, sounds and dialogues. In her practice, she plays with barely-visible borders between reality, fiction and politics, while Simnett places herself into the scripts not only as the storyteller, but also the sorcerer, the observer and, eventually, the artist. Simnett’s current solo exhibition My Broken Animal continues at the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem until 23rd of February. We had a conversation about how fables and tales, processes of excess and Surrealism play into her practice, and about how she became to be an artist in the first place.

Mine Kaplangı: Marianna, how did you begin making art?

Marianna Simnett: As a child I would draw all my presents and return them to the giver as a drawing. I meticulously rendered fivers, Twix wrappers, Pez dispensers, puppets, candles, dolls. There was a story I enjoyed reading, about a boy who could turn any drawing into reality, but the village got greedy and wanted him to keep drawing gold. So he had to leave a tiny bit incomplete. I read stories and loved magic. I looked in the mirror aged seven and drew a black line down my middle, splitting my body in two. I stared at my divided self and knew something strange was happening. It was a ‘do or die’ calling, a promise to myself which I have kept ever since.

MK: One can find these magical references to certain types of mythical creatures, animals from fables and monsters or witches from folk or fairy tales in your work. Did you grow up listening to folktales as well and were you always fascinated or affected by these stories?

MS: I grew up on Aesop’s fables and Yugoslavian folktales. I was gripped by the Children’s bible. It’s absurdism mixed with moralism. I invented stories with my father and there would always be fairies, orange flamingos and mythical creatures. There was the ‘dunno’ –– a shaggy, shape-shifting creature, with red eyes, big fluffy paws with claws underneath if he needed them. I read and played music from the age of five.

Marianna Simnett, Above: Plucker, 2019 Below: Hyena and Swan in the Midst of Sexual Congress, 2019

Marianna Simnett, Above: Plucker, 2019 Below: Hyena and Swan in the Midst of Sexual Congress, 2019

Installation view "My Broken Animal" a Frans Hals Museum, Courtesy: The artist. Photos: Charlott Markus

Marianna Simnett, Above: Plucker, 2019 Below: Hyena and Swan in the Midst of Sexual Congress, 2019

Marianna Simnett, Above: Plucker, 2019 Below: Hyena and Swan in the Midst of Sexual Congress, 2019Installation view "My Broken Animal" a Frans Hals Museum, Courtesy: The artist. Photos: Charlott Markus

MK: Currently you have a solo exhibition at the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem titled My Broken Animal. Could you tell me more about the exhibition and what kind of works it presents?

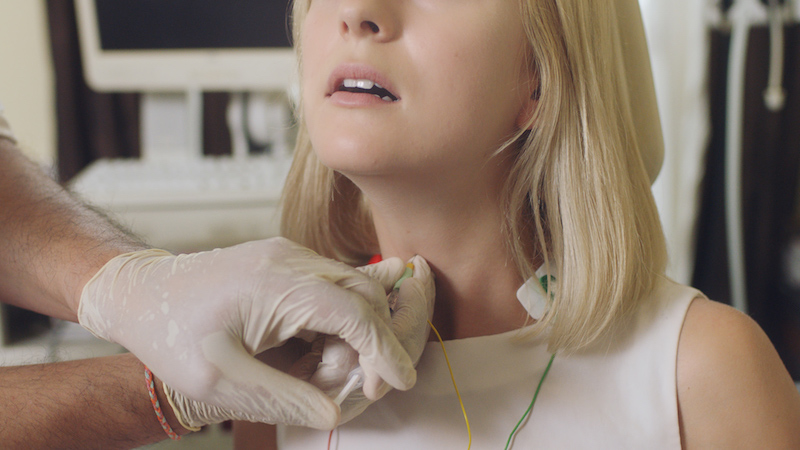

MS: It brings together six works which all relate to mutating creatures and warped bodies. The first room is conceived as a deranged child’s playroom. Oversized squishy animal toys - a swan, a hyena, a rabbit and a bird - are misbehaving. The hyena and swan are having sex in an orgiastic tableaux, the pink rabbit is hung upside-down, going round and round on a carousel, the bird’s feathers have all been plucked out. There is implicit violence but the room is delightfully colourful and tactile. In the rest of the show there are two films and an installation. The Needle and the Larynx (2016) portrays a girl having her larynx injected with Botox to lower the pitch of her voice; Faint with Light (2016) documents the sound of my body fainting set to blinding LED lights, The Bird Game (2019) is a wicked fairy tale about a crow who lures a group of children into playing a game so that they may never need to sleep again.

MK: You employ aspects of symbolism and surrealism from the past to address current political and sociological frustrations, creating grotesque universes. How would you describe your practice’s relation to symbolism and surrealism?

MS: The image or the razor blade slicing through the eye in Un Chien Andalou (1929) has never left me. I love Luis Buñuel’s films. I think Surrealism at its worst gets mistaken for privileged wandering or dreaming, but I like it for its ability to awaken fears and to describe unfiltered thoughts. There is a lot of censorship around us, which Surrealism, with its images of insects, defecation, desecration has showed us to ignore. Fantasy and reality are not oppositional genres to me. I think what I’m doing is very real. I’m just tuning in. Ursula le Guin says: “Fantasy is not antirational, but pararational; not realistic but surrealistic, a heightening of reality. In Freud’s terminology, it employs primary not secondary process thinking. It employs archetypes which, as Jung warned us, are dangerous things. Fantasy is nearer to poetry, to mysticism, and to insanity than naturalistic fiction is. It is a wilderness, and those who go there should not feel too safe.”

Marianna Simnett, The Bird Game, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photo: Charlott Markus

Marianna Simnett, The Bird Game, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photo: Charlott Markus

Marianna Simnett, The Bird Game, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photo: Charlott Markus

Marianna Simnett, The Bird Game, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photo: Charlott Markus

MK: Your work The Bird Game (2019) was recently presented at the London Contemporary Music Festival. The performative and possessive element of your video was inescapable. It was a truly physical experience, almost like a session or an intensely vivid dream. I remember the spontaneous silence right after the ending before the audience started clapping. I looked around, and everyone was trapped in their own minds dealing with the reality of those dark, yet whimsical elements of your video for minutes. How did you develop The Bird Game and how was the making for you?

SM: The film was a commission to commemorate the anniversary of the Evelina Children’s Hospital. I was thinking about the state of children’s mental health and anxiety, about gamification and addiction. I was also fascinated by birds’ ability to stay awake for extensively long periods, undermining the common thought that sleep is necessary for survival. Woven into the film are mangled versions of Sleeping Beauty and extracts from Ovid’s Metamorphosis. The film has no breathing space. It’s as if a rocket goes off the moment Crow flies down from her branch. Forward, forward, forward, up, up, up, and finally out of the window. There’s a lot of pressure, hence perhaps why it feels so anxious.

MK: Many of your films’ leading actors are children, which makes these seductively captivating journeys even more challenging to experience. Is there a specific reason why you prefer to work with children, especially for your video works?

MS: Because they are like play-dough! Ha. No, children are smart. And they can also be very cruel. We project a lot of innocence onto children. It’s just what grown ups like to think, maybe it gives them a purpose to try to save them. Also, their bodies are growing and spurting out of control. Those subtle body behaviours I find fascinating. Like you’re wearing your body like a costume, it doesn’t quite feel your own.

Marianna Simnett, Fainth with light, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photos: Charlott Markus

Marianna Simnett, Fainth with light, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photos: Charlott Markus

Marianna Simnett, Fainth with light, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photos: Charlott Markus

Marianna Simnett, Fainth with light, 2019, Installation view "My Broken Animal" at Frans Hals Museum. Courtesy: The artist. Photos: Charlott Markus

MK: The installation Faint with Light (2016) from the exhibition is one of the most abstract works of yours. It consists of sound recordings of inducing your own body to faint, by hyperventilating. How did this work come about?

MS: The piece was inspired by my late Croatian grandfather, who fainted when he was supposed to be shot in a firing line during the Holocaust. I decided to make myself faint until I couldn’t anymore, that ended up being four times until I had a seizure and couldn’t continue. The sound of my breath triggers blinding rows of light in a pitch-black room. It can be unbearable to experience.

MK: Through storytelling, you tend to keep the audience in-between reality and fiction, which is a very slippery state. Considering the imagery of your work, it is much more than a duality, but rather a choice. It is more of a journey that sticks with you after experiencing the work. The works are reminders of how we face stories, how we access history and of the privileges belonging to the ones who are telling and distributing them. Do you think the art of storytelling should be political?

MS: Storytelling is highly political. Look at Marina Warner’s project Stories in Transit, which explicitly focuses on storytelling as a form of shelter in situations of exile and dispossession. The least political work is the one that doesn’t also embrace poetics.

Marianna Simnett, The Needle and the Larynx (video still), 2016. Courtesy the artist and Serpentine Galleries, London

Marianna Simnett, The Needle and the Larynx (video still), 2016. Courtesy the artist and Serpentine Galleries, London

MK: All of your works are profoundly layered, addressing many topics at the same time. What are you working on at the moment?

MS: I am becoming very interested in cannibalism. Meanwhile I am writing a feature film and working on upcoming shows at IMA Brisbane, Castello di Rivoli, and devising a live performance about bird screams for voice and flute.

Marianna Simnett

My Broken Animal

Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Netherlands

until 23rd of February

www.franshalsmuseum.nl

Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Netherlands

until 23rd of February

www.franshalsmuseum.nl