Mariana Cánepa Luna & Max Andrews from Latitudes. Photo © Eunice Adorno (2012)

I met the curator Mariana Cánepa Luna during her talk with the Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui at her current exhibition “Agras Volcano. Mining Rights” at the IVAM in Valencia. Afterwards we had such a lively discussion on the discourse of the Anthropocene and environmentally-engaged art that I felt the need to deepen our conversation even further. Together with the curator Max Andrews, in 2005 Mariana founded the curatorial office Latitudes, based in Barcelona. As they write, their current research focuses on “material narratives, biographies of objects, and a world-ecological perspective on art histories”. An interview with two pioneers on their curatorial practice and writing about the urgency of a geological understanding of the world, how to “think with” and from a perspective of different objects and the challenges of curating…

Helene Romakin: Latitudes has realised over 50 projects including a wide variety of formats such screenings, exhibitions, editorial projects, and many more. How do you maintain the high quality of your work considering the high intensity of production?

Max Andrews: The intensity of work has varied considerably over the years and the seasons. Yet the obligatory answer is also the corniest one, the “chef’s secret”: using the best ingredients. We have been lucky to work with and learn from some amazing artists and fellow curators. Extending the food analogy, we have worked in more academic aspects of cultural theory (attested by the many workshops and lectures we have been involved in), yet have always relished the hands-on “farm-to-table” production of projects with a broad public appeal, such as the multi-venue “Compositions” projects that we devised for the Barcelona Gallery Weekends in 2015 and 2016.

Reenactment of a 1972 performance by Robert Llimós connecting all the participating venues, part of the commissioning series ‘Composiciones’, Barcelona Gallery Weekend 2016. Photo: Roberto Ruiz.

Some projects have spanned several years and have emerged from slow-burn concerns, obsessions, and fieldwork – such was the case with the “4.543 billion. The Matter of Matter” show at CAPC in Bordeaux. We joked with the staff that it only took us a decade to research! While others have come to us at (sometimes alarmingly) short notice, demanding an almost just-in-time or on-demand model of curating. We have quite deliberately worked under the identity of a curatorial office, in the sense of an architecture office or design office, in that some projects are more like a response to a brief, or the needs of a given “client”, whereas others have been self-generated and, some might say, came into the world in a way more akin to the work of an artist. Naturally many are a combination of both of these tendencies. What is not apparent from the Projects page of our website is the number of proposals that were unrealized or lie dormant for one reason or another. There is a lot of frantic paddling below the surface.

Several years ago we gave a lecture about curating as a form of detective work or courtroom drama, and I still believe that being able to solicit (in the sense of lobbying for, entreating, hustling even) and advocate (supporting, arguing on behalf of) while maintaining dignity is something both essential for survival and for supporting the work of the artists we admire. Over the years we have developed a great appreciation for the sweeping 'longue durée' approach of a world-systems perspective, yet at the same time we really value the meticulousness of micro-history. I suspect this has somehow lent our work a peculiar sense of attention to detail and continuity. More prosaically I think we were both the kind of children who always got their homework in on time.

Mariana Canépa Luna: The intensity part of your question has never been that conscious, more a result of needing to support ourselves financially. We very much learn through making, one thing leading to another in an organic way. Only when the financial crisis hit – slowing down the sector, arts programming and hence income – did we really realise the stress we had put ourselves through at certain periods of our lives.

HR: Speaking of 'longue durée', many of your projects involve long-term collaborations. For example, you have worked with Lara Almarcegui several times since 2005. Could you tell me how this collaboration developed over the years? What are the challenges and prospects of such a profound professional relationship?

MCL: Lara is probably the artist we’ve collaborated with most often, and it’s delightful, just like any long-term friendship. Much of our collaboration has been editorial, as we have written several essays and profiles centred on her work, culminating in 2011 when we edited her first monograph. We have many common interests and friends, so that has kept us connected since we met in person back in 2005.

MA: In the early years we also worked repeatedly with other artists such as Jordan Wolfson or Tue Greenfort, and we feel we have an on-going conversation in several capacities with Maria Thereza Alves, Amy Balkin, Mariana Castillo Deball, Christina Hemauer & Roman Keller, Antoni Hervàs, Sean Lynch, Nicholas Mangan, Jorge Satorre, and Haegue Yang, just to mention a few.

Hike to Stanley Glacier in the Kootenay National Park with participants of the residency-seminar ‘Geologic Time’ led by Latitudes. Banff International Curatorial Institute, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, Banff, Canada, 11 September–6 October 2017. Photo: Latitudes.

HR: Many of your projects deal with art surrounding the discourse of the Anthropocene. Have you always been interested in Environmental Art?

MCL: The long curatorial focus on so-called environmental issues came in part from our first project in 2005 in the context of the Arts & Ecology programme of The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (RSA) in London. With the RSA we curated two foundational projects for us: we worked with Danish-artist Tue Greenfort in a three-year-long public commission, and we edited the publication “LAND, ART: A Cultural Ecology Handbook” (2006). But going back in time, Max has been an avid birder since he was a child so art and the environment converged naturally, one could say.

MA: We’ve never been interested in the woven twigs and recycled-bottle sculptures of “environmental art”. More generally, it is not a concept we find particularly helpful. On the one hand it is too narrow, too susceptible to romanticism and the fiction that natural systems are separate from human activities, a vision that is profoundly Eurocentric and colonial. Yet on the other, it is too general. Perhaps any work of art could be interpreted as environmental art in the sense that it has a particular energy footprint, economy, material composition, and place in the web of life. As Giovanni Levi has written, “it becomes immediately obvious that even the apparently minutest action of, say somebody going to buy a loaf of bread, actually encompasses the far wider system of the whole world’s grain markets”.

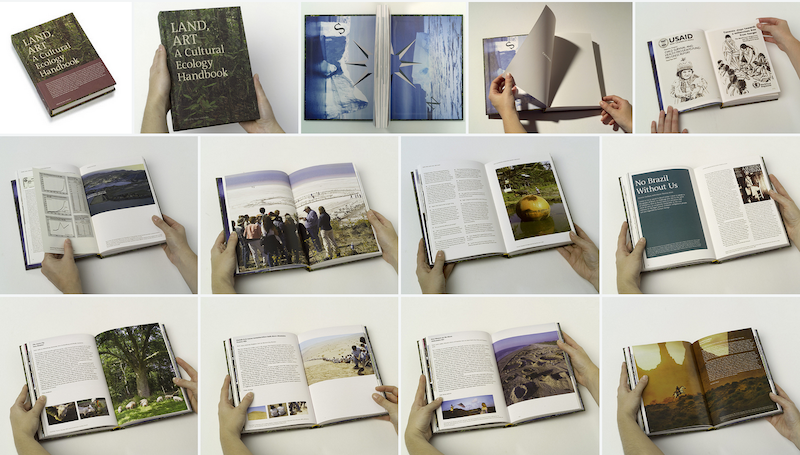

Page spreads from the publication ‘LAND, ART: A Cultural Ecology Handbook’ (2006) ed. Max Andrews. Published by The Royal Society of Arts’ Arts & Ecology programme, in partnership with Arts Council England. Photos: Robert Justamante. Courtesy: Latitudes.

HR: Could you speak more about the publication “LAND, ART: A Cultural Ecology Handbook”?

MCL: The project was commissioned by the RSA, in partnership with Arts Council England. Through the inspirational contributions of people as varied as Lucy Lippard, Stephanie Smith, Winona LaDuke, or the late Wangari Maathai – to mention just a few – the compendium charted the twin legacies of Land Art and the environmental movement while proposing how the critical acuity of art might remain relevant in the face of the dramatic ecological consequences of human activity. The research and reflection involved set Latitudes on a course that led to several further projects engaging with ecology, explicitly or otherwise.

The publication is now more than ten years old. At the time “LAND, ART...” was launched at an event at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), Tony Blair was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, George W. Bush was President of the United States, and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero was Prime Minister of Spain. The landmark Stern Review on the economics of climate change had just been published two months earlier; the notion of the Anthropocene had yet to become widely discussed, having been first proposed in print in 2002.

MA: The “cultural ecology” part of the book’s title drew on Félix Guattari’s “The Three Ecologies” (1989) and its three-pronged characterization of ecological thought and action – environmental ecology, social ecology, and mental ecology. Why not cultural ecology? Or indeed curatorial ecology, ecological art history, etc.? Guattari realised that new humanities were required to venture beyond the great divide wrought between nature and society.

Under the government of U.S. President Donald Trump regulations deemed too burdensome to the fossil fuel industry and other big businesses are being targeted. For example, oil and gas companies no longer have to declare methane emissions; the prohibition of hydrofluorocarbons, powerful greenhouse gases, is no longer enforced; offshore drilling safety regulations have been loosened; a ban on the hunting of predators in Alaskan wildlife refuges has been overturned; a rule that prevented coal companies from dumping mining debris into streams has been revoked; payments to the Green Climate Fund, a United Nations program, have been cancelled. In the same “The Three Ecologies”, Guattari presciently wrote:

“Just as monstrous and mutant algae invade the lagoon of Venice, so our television screens are populated, saturated, by ‘degenerate’ images and statements. In the field of social ecology, men like Donald Trump are permitted to proliferate freely, like another species of algae, taking over entire districts of New York and Atlantic City; he ‘redevelops’ by raising rents, thereby driving out tens of thousands of poor families, most of whom are condemned to homelessness, becoming the equivalent of the dead fish of environmental ecology.”

Views of the exhibition ‘4.543 billion. The Matter of Matter’ at the CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, France, 29 June 2017–7 January 2018. Photo: Latitudes / RK.

HR: One of your latest curated projects “4.543 billion. The matter of matter” at the CAPC musée d’art contemporain Bordeaux in 2017-18 involved over 30 artists who engage with topics such as geological time in correlation to cultural histories, ecological processes and the continuum of materials and temporal landscapes. Could you talk more about the concept and the realisation of the exhibition?

MCL: The starting point for the exhibition was thinking from the ecological and the geological, and a perspective where art works could be conceived as dynamic organic and inorganic matter through time, raw materials with a particular mineral, energetic, and chemical legacy, rather than primarily as unchanging authored objects that seemingly only make sense within the human construction of art history. Throughout the process we wanted to undo the notion of the autonomous artwork and instead present art as part of a material continuum of various qualities: whether of raw materials, archives, documentation, evidence of, or commentary on.

Another element was linking this with the notion of “petrolism” and extractive modernities. Quite a bit of work has already been done in terms of exhibition making around fossils fuels and the capitalist system but we wanted to take on a broader (or rather, deeper and longer) geological or mineral perspective in which the agency or exploitation of the entire lithosphere came into play. Coal is comprised of ancient forests, limestone (including the particularly coarse limestone that the CAPC building is made of) is made of compressed sea creatures, and this also brought into focus the notion of strata as archives, and the poetic possibilities of the visual similarities between, for example, a stack of paper documenting the construction of the museum building (a former colonial commodities warehouse) and layers of sedimentary rock.

MA: Art’s links with the capitalist system based on resource extraction are much more apparent and palpable that you might think. Many of the great collections of modern art, from the Guggenheim to the Rockerfeller-founded MoMA – one could argue the very idea of modern art itself – was literally funded and fuelled by money from drilling or mining. The wealth of the earth was transacted into paintings and sculptures. One of the key works in the show by Terence Gower (“Public Spirit / Wilderness Utopia”, 2008) told the story of Joseph Hirshhorn (whose collection formed the basis of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington) and his fortune made mining uranium. This refrain about the geological underpinnings of culture was also drawn out through the juxtaposition of a piece by Martin Llavaneras (“Touchpad”, 2016) comprising worn lithographic stones, with a lithograph from a colonial-era botanical guide to the plants of the Antilles (Étienne Denisse, “Le Cacaoyer”, 1835). The cheap mass reproduction of images was made possible thanks to the technique of lithography and the qualities of a particularly fine-grained limestone from Bavaria.

The lithograph also was also one of several reminders of where the prosperity of Bordeaux came from: at its height the museum building would have been full of cacao and coffee from the Caribbean, as well as pepper, sugar, rice, rubber, and so on. We wanted to draw out the notion of the reciprocal landscapes, in that the stone of the walls and the wood of the beams of the museum building would be not only reflected in an absence in quarry or a forest, but that the wealth of the city was a direct result of off-shoring labour and agriculture to the colonies. This notion of the “free” labour of both human and non-human nature in the production of value for capital was a really important one, as was a critical perspective on the Anthropocene thesis: ecological ruination is not the generic, unwitting fault of all mankind, but the result of specific and identifiable practices.

HR: If you had to predict how art production will develop in the next 10 years, what would you anticipate?

MCL: On the institutional front, museums are no longer getting away with accepting certain dubious funding from donors or having problematic trustees on their boards. The National Portrait Gallery in London, the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum in New York have recently rejected financial support from the Sackler family, owners of the American pharmaceutical company that makes the addictive prescription painkillers OxyContin, while others like the V&A have controversially defended the support. The CEO of the Serpentine Gallery recently resigned over her husband’s investment in an Israeli spyware firm, and so has the vice chairman of the Whitney Museum of American Art amid criticism towards his law enforcement and military supplies company Safariland. Such movements toward a more just and civil society could now be considered meaningful climate actions.

MA: Like Mariana I wonder more how institutions themselves will ecologise. What we know today as contemporary art really came of age in the 1990s and it is deeply integrated with the notion of globalisation. Last summer we saw “Museum of Obsessions” at Kunsthalle Bern, a fascinating exhibition dedicated to the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann. Among the ephemera, correspondence, artworks, and photographs that documented exhibitions was a mass of luggage tags accumulated from more than fifty years of flights in and out of ZRH, GVA and BRN. Bar-code strips, gate-check dockets, and business-class labels, were peppered with the words ‘Priority’, ‘Rush’, and ‘Short Connection’. Credited as an artwork by Szeemann (“Travel Sculpture”, late 1960s–2004, mixed media) this bag-tag totem hung for many years in the Fabbrica Rosa, his archive and library in Maggia, Switzerland, before it was purchased by the Getty Research Institute and transported to Los Angeles. “Travel Sculpture” is today an irrefutably uncomfortable object, a testament to frequent-flyer Szeemann’s curiosity, celebrity, and privileged right to roam, yet evidence of the relentless growth of air travel during his lifetime, and the climate peril of normalizing hypermobility. I am not suggesting a kind of km0 curating, but you do have to wonder what new models and values will prevail in a future where Szeemann’s luggage tags might look as unacceptable as colonial loot.

Interview by Helene Romakin

Latitudes Website:

https://www.lttds.org