Sara Cwynar, Rose Gold (filmstill), 2017

Sara Cwynar, Rose Gold (filmstill), 2017 All images © Sara Cwynar

The work of Vancouver-born artist Sara Cwynar emerges from her archives and her personal collections of visual materials. In her photographs, collages, installations and books she explores the circulation of images and their changes in meaning over time and in different cultures, as well as how this affects a collective worldview. For Sara, exploring the nature of photographic images is as important as the limitations of the medium itself. She received an MFA in Photography from Yale University, New Haven, and studied English Literature and Graphic Design in Canada before. Her solo exhibitions include presentations at the MMK Museum of Modern Art, Frankfurt/Main, at Foxy Production, New York, and at Cooper Cole, Toronto. Furthermore, Sara took part in numerous international group shows.

Jürgen Dehm: Hi Sara, in your book “Kitsch encyclopedia” (2013) you combine writings on Kitsch by the likes of Milan Kundera, Roland Barthes or Jean Baudrillard with your personal understanding of kitsch. How did this project evolve?

Sara Cwynar: I first made this project when I was a graphic design student in Canada. I was collecting all sorts of images of the type you could call 'public images' from advertising, encyclopedias, history books, photographic manuals - and I was trying to figure out what connected all this material. When I stumbled upon Kundera's definition of 'Kitsch' it seemed perfect. His idea is that 'Kitsch' is all the sort of idealised imagery we look at in order to ignore was is not aesthetically appealing about life - most fundamentally that it ends in death. This can mean a religious icon, a political movement, a lot of the products of advertising. It is about how we built an idealised image world on top of the real world and live in it. Barthes and Baudrillard talk about these ideas too in different ways.

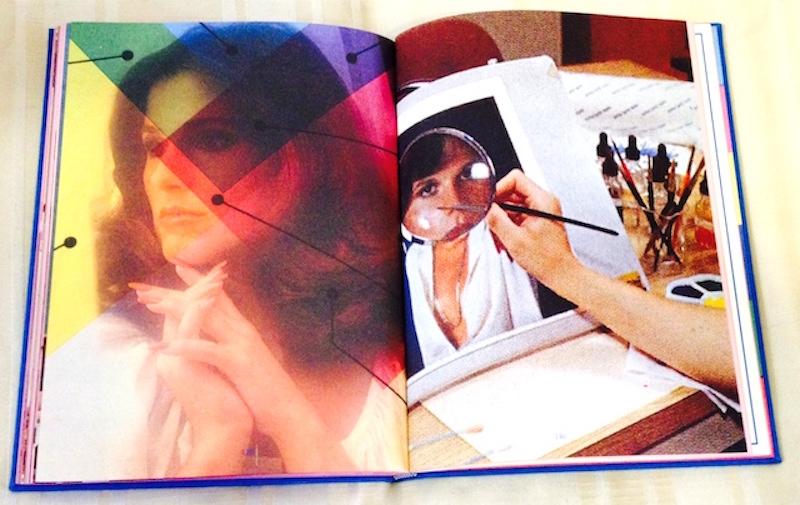

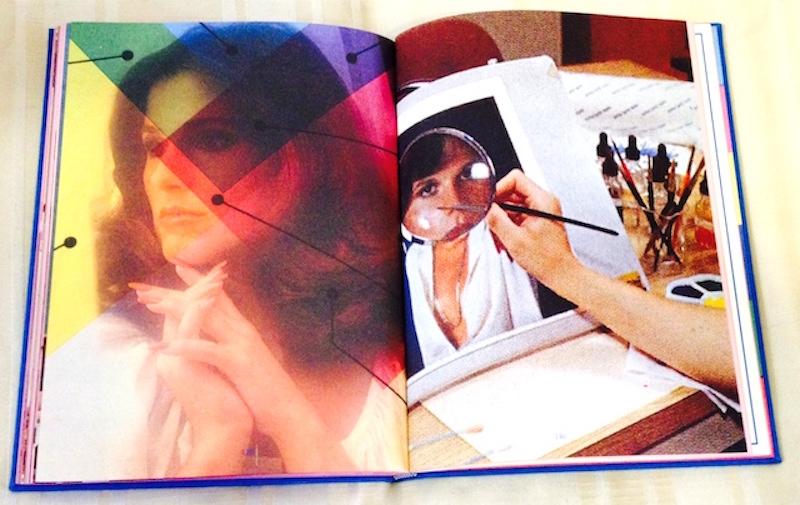

Sara Cwynar, The Kitsch Encyclopedia (2013)

Sara Cwynar, The Kitsch Encyclopedia (2013)

JD: But “Kitsch Encyclopedia” was not your first book. Already in 2010 you published “Ornamental Cookery”. What fascinates you about books?

SC: I think that books are a more democratic way to share ideas and images, if you do an art show the project is up for a few weeks and a few people get to see it, not everyone is even comfortable entering the space of the gallery. With a book, it can move around for years, fall into different hands, it is much more accessible. I also have a background as a graphic designer so I love to design books.

JD: Would you rather call yourself a photographer or a conceptual artist?

SC: I think of myself as more of a conceptual artist who uses and mines photography as a tool. My work is increasingly taking the form of essay-style videos that meander through different ideas about how images and designed objects work in our culture, how these things infiltrate our minds and shape how we see the world, ourselves and our shared history.

JD: What fields are you interested in when you research and why?

SC: Increasingly I am thinking about standards, and how color printing, or the cosmetics industry for example, try to standardise intangible things like skin tone or natural colors. I am thinking about the political meanings contained in even our most banal seeming objects and images.

JD: How do you start a new work?

SC: Sometimes I start with an object and sometimes with a piece of writing or an image, it can really come from anywhere. Often I will have things kicking around the studio for months or even years and then one day I just suddenly know what to do with them.

JD: What is it that intrigues you about the objects from your “Soft Film” (2016)?

SC: In “Soft Film”, I was really drawn to these velveteen boxes that I was collecting from eBay. I liked how they were not the intended object, like they were just the holder for the actual product - the jewelry, and because of that they had sort of faded and been discarded and lost. Many of them have warped quite beautifully with time and use. And because they are essentially packaging, they are very heavily designed, often in ways that feel anachronistic now. There is a lot of optimism in the way they were made, and they have been emptied of that. I think the objects say a lot about how value works, how things circulate in economies other than the ones they were intended for, and how we kind of use things up.

JD: Old velveteen jewelry boxes play a central role in “Soft Film“. How does their soft surface relate to other objects and images in the film?

SC: In the film, I wanted to talk about this term, soft sexism, that had been in the news a lot. It originated in Silicon Valley and it describes subtle forms of discrimination leveled against women - for example, how women might be asked easier questions than men or left out of social gatherings, and it keeps them from reaching their full potential, but it’s also hard to put your finger on. I was using the soft boxes as a kind of vessel or visual accompaniment to talk about soft sexism. Then the film meanders into a larger voice over about how we value objects and what this could tell us about how we value humans too.

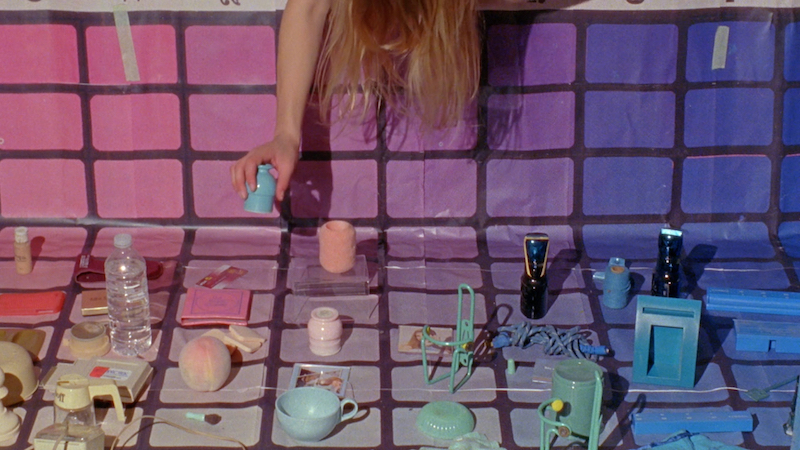

Above: Sara Cwynar, Soft Film (filmstill), 2016 and below: Rose Gold (filmstill), 2017

Above: Sara Cwynar, Soft Film (filmstill), 2016 and below: Rose Gold (filmstill), 2017

JD: Why did you decide to shoot on 16mm and then transfer it to Video?

SC: I chose to shoot on 16mm because I wanted the film to have the sensibility of a kind of outmoded heyday of advertising, which is when a lot of the materials discussed in the film are from. Since the film is about time and value, how we value things differently over time, I wanted the film to combine anachronistic images with images that could only have been made right now (like the Nikes), so that the form reflects the content in a way. I also think the color palette is very important to tie everything together, and film allows you to have very specific, saturated colors.

JD: What does nostalgia mean to you?

SC: I think nostalgia is dangerous! I am trying to look back at the past and think about what objects and images from a recent history can tell us about the current moment, and what subtle power dynamics might be contained in these things that have led us to where we are now. Even though the color palette and objects I use are often from earlier eras, I don’t think the work is necessarily nostalgic, it is actually quite critical of the past.

Sara Cwynar, Self Portrait, 2015

Sara Cwynar, Self Portrait, 2015

JD: Do you have a favorite pair of sneakers?

SC: Nike bright pink Comme des Garçons sneakers right now!

JD: What is your next project going to be about?

SC: A new film about color standards and cosmetics.

Jürgen Dehm: Hi Sara, in your book “Kitsch encyclopedia” (2013) you combine writings on Kitsch by the likes of Milan Kundera, Roland Barthes or Jean Baudrillard with your personal understanding of kitsch. How did this project evolve?

Sara Cwynar: I first made this project when I was a graphic design student in Canada. I was collecting all sorts of images of the type you could call 'public images' from advertising, encyclopedias, history books, photographic manuals - and I was trying to figure out what connected all this material. When I stumbled upon Kundera's definition of 'Kitsch' it seemed perfect. His idea is that 'Kitsch' is all the sort of idealised imagery we look at in order to ignore was is not aesthetically appealing about life - most fundamentally that it ends in death. This can mean a religious icon, a political movement, a lot of the products of advertising. It is about how we built an idealised image world on top of the real world and live in it. Barthes and Baudrillard talk about these ideas too in different ways.

Sara Cwynar, The Kitsch Encyclopedia (2013)

Sara Cwynar, The Kitsch Encyclopedia (2013) JD: But “Kitsch Encyclopedia” was not your first book. Already in 2010 you published “Ornamental Cookery”. What fascinates you about books?

SC: I think that books are a more democratic way to share ideas and images, if you do an art show the project is up for a few weeks and a few people get to see it, not everyone is even comfortable entering the space of the gallery. With a book, it can move around for years, fall into different hands, it is much more accessible. I also have a background as a graphic designer so I love to design books.

JD: Would you rather call yourself a photographer or a conceptual artist?

SC: I think of myself as more of a conceptual artist who uses and mines photography as a tool. My work is increasingly taking the form of essay-style videos that meander through different ideas about how images and designed objects work in our culture, how these things infiltrate our minds and shape how we see the world, ourselves and our shared history.

JD: What fields are you interested in when you research and why?

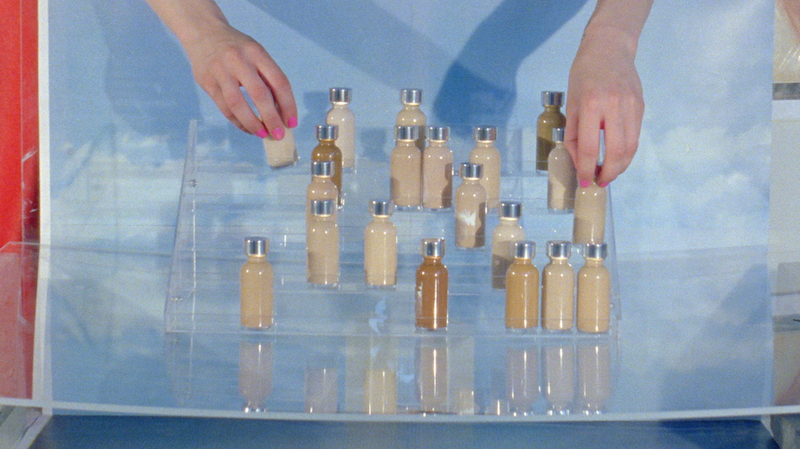

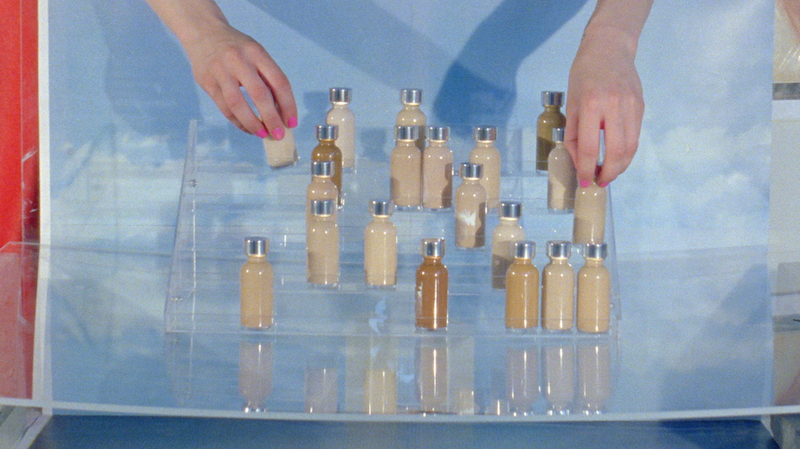

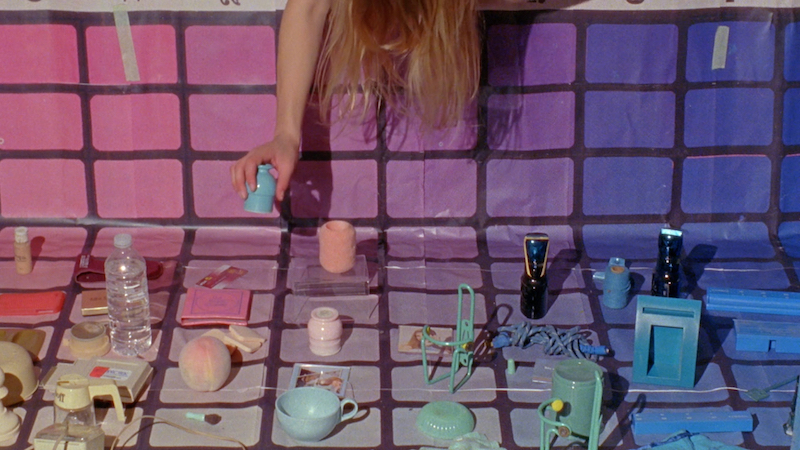

SC: Increasingly I am thinking about standards, and how color printing, or the cosmetics industry for example, try to standardise intangible things like skin tone or natural colors. I am thinking about the political meanings contained in even our most banal seeming objects and images.

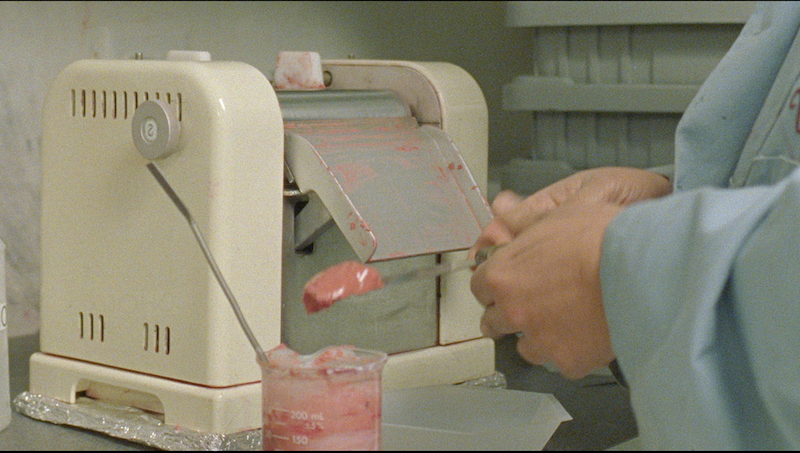

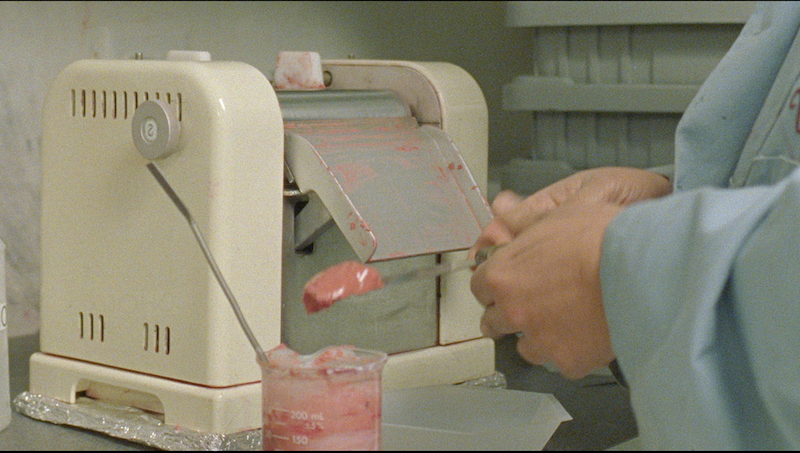

Sara Cwynar, Cover Girl (3 filmstills), 2018

JD: How do you start a new work?

SC: Sometimes I start with an object and sometimes with a piece of writing or an image, it can really come from anywhere. Often I will have things kicking around the studio for months or even years and then one day I just suddenly know what to do with them.

JD: What is it that intrigues you about the objects from your “Soft Film” (2016)?

SC: In “Soft Film”, I was really drawn to these velveteen boxes that I was collecting from eBay. I liked how they were not the intended object, like they were just the holder for the actual product - the jewelry, and because of that they had sort of faded and been discarded and lost. Many of them have warped quite beautifully with time and use. And because they are essentially packaging, they are very heavily designed, often in ways that feel anachronistic now. There is a lot of optimism in the way they were made, and they have been emptied of that. I think the objects say a lot about how value works, how things circulate in economies other than the ones they were intended for, and how we kind of use things up.

JD: Old velveteen jewelry boxes play a central role in “Soft Film“. How does their soft surface relate to other objects and images in the film?

SC: In the film, I wanted to talk about this term, soft sexism, that had been in the news a lot. It originated in Silicon Valley and it describes subtle forms of discrimination leveled against women - for example, how women might be asked easier questions than men or left out of social gatherings, and it keeps them from reaching their full potential, but it’s also hard to put your finger on. I was using the soft boxes as a kind of vessel or visual accompaniment to talk about soft sexism. Then the film meanders into a larger voice over about how we value objects and what this could tell us about how we value humans too.

Above: Sara Cwynar, Soft Film (filmstill), 2016 and below: Rose Gold (filmstill), 2017

Above: Sara Cwynar, Soft Film (filmstill), 2016 and below: Rose Gold (filmstill), 2017JD: Why did you decide to shoot on 16mm and then transfer it to Video?

SC: I chose to shoot on 16mm because I wanted the film to have the sensibility of a kind of outmoded heyday of advertising, which is when a lot of the materials discussed in the film are from. Since the film is about time and value, how we value things differently over time, I wanted the film to combine anachronistic images with images that could only have been made right now (like the Nikes), so that the form reflects the content in a way. I also think the color palette is very important to tie everything together, and film allows you to have very specific, saturated colors.

JD: What does nostalgia mean to you?

SC: I think nostalgia is dangerous! I am trying to look back at the past and think about what objects and images from a recent history can tell us about the current moment, and what subtle power dynamics might be contained in these things that have led us to where we are now. Even though the color palette and objects I use are often from earlier eras, I don’t think the work is necessarily nostalgic, it is actually quite critical of the past.

Sara Cwynar, Self Portrait, 2015

Sara Cwynar, Self Portrait, 2015 JD: Do you have a favorite pair of sneakers?

SC: Nike bright pink Comme des Garçons sneakers right now!

JD: What is your next project going to be about?

SC: A new film about color standards and cosmetics.