© Indrė Šerpytytė "03" from the series 150mph (2015)

© Indrė Šerpytytė "03" from the series 150mph (2015)

Sanna Moore, curator for contemporary art at the Imperial War Museum in London, on the exhibition "Age of Terror: Art after 9/11", on strategies of representing war and terror through art, and on how contemporary art fits into the structures of a war museum.

Anna-Lena Werner: "Age of Terror: Art after 9/11" at the Imperial War Museum London shows 50 artistic responses to the attacks of 9/11, taking into account personal, political and social conflicts that were consequences from the initial attacks. Why does the show take place now?

Sanna Moore: The museum noticed a change in art after the attacks of 9/11 and had planned an exhibition for a long time. Last year I was invited particularly for the curation of this exhibition within the Team on Contemporary Conflicts. I looked at around 400 artists in that one-year research period. There is a huge wealth of material. I think also the way the Internet informs how artists respond to that we're so heavily informed these days with everything and that feeds into the artists' practice.

ALW: Is that why the exhibition puts such an emphasis on artistic reflections on how the media dealt with 9/11 and the London bombing?

SM: Yes, I think what is interesting about this section is that some artists have responded immediately, and then other artists come back years later, looking back at media images. I'm thinking particularly of Indrė Šerpytytė, who is taking the images of the Twin Tower jumpers and then translated that image into paintings. She was doing that 2014-2015, with a distance and quite reflective, but very much through the photography at that time. Also in the work "216 Westbound" (2014) of Shona Illingworth, whose work is a response to the 7/7 London Bombing. That work is telling the story of John Tulloch who survived that attack, but it's also putting it into the context of state control and how the use of his image in the media contributed to his distress. He was upset about his images being used to promote a government bill that he was not in favour of. That theme of media images goes through different aspects of the exhibition.

© Shona Illingworth "216 Westbound" (2014)

ALW: Did you have a starting point for your research or one particular work of art that you came from?

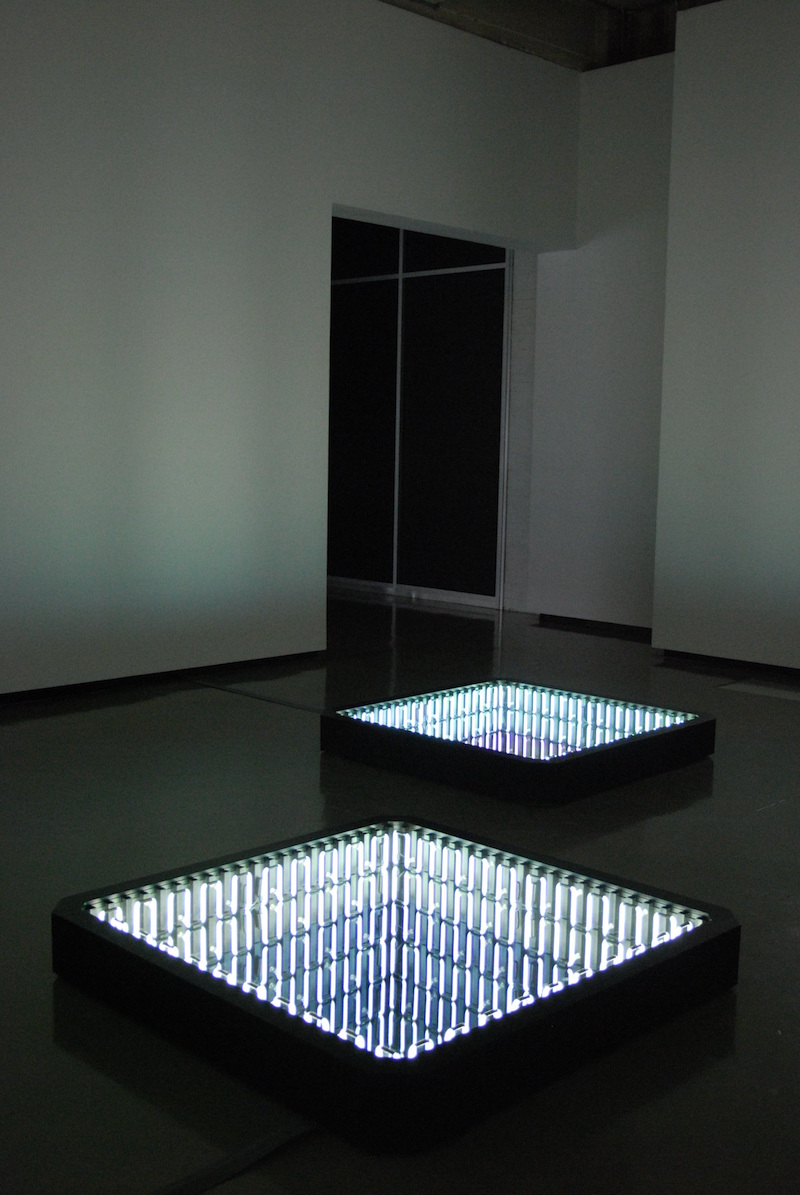

SM: Probably the key work in my head was the 9/11 painting "September" by Gerhard Richter. That was the visual starting point and the first work we approached to loan. We didn't get the loan so we have a print in the exhibition. It was the starting point in terms of an artist who had some history in representing conflict through his practice, but also had a personal experience of 9/11, but didn't respond immediately but a few years later. Grayson Perry's vase that he made on 9/12 came very soon after. And Ivan Navarro's "The Twin Towers" I found in my first week in the role of the curator here, because I had worked with Ivan previously, so I knew he had a history of making political work.

ALW: Navarro's very immersive work is the third work of the show, following an emotional video of Tony Oursler's personal experience of 9/11 and a conceptual piece of Hans-Peter Feldmann, who collected dozens of Newspaper Front Pages on 9/12. Spectators are not guided through the exhibition in soft transitions, but the intensity of the works is constantly changing.

SM: Yes, the visitor really has to work. That has annoyed some people. But with this subject matter I think you should feel that when you come out. I tell people you need to take time, you cannot rush through, and it is exhausting.

ALW: Well, the theme is exhausting.

SM: There are a couple of lighter moments in there, but really only a couple, because, you know, we are in a War Museum after all.

Above: © Grayson Perry “Dolls at Dungeness September 11th 2001” (2001)

Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London / Photo Stephen Brayne

Above: © Grayson Perry “Dolls at Dungeness September 11th 2001” (2001)

Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London / Photo Stephen Brayne Below: © Hans Peter Feldmann "9/12 Front Page" (2001)

ALW: A particular problem for War Museums is the balance of avoiding to trivialise art works in order make them accessible for all spectators, including school classes, and in contrast, of displaying exhibitions filled with aestheticised horror and misery. What is your take on this?

SM: It think it is difficult with this subject matter. You are putting in works in there that have huge depths. And you are juxtaposing these works to others, such as Grayson Perry's vase "Dolls at Dungeness September 11th 2001," which is an immediate response. The day after he just does is. To some people this meant that he was trivialising the event, but to me it doesn't mean that at all. It's just an instant response – this is just as important as the one that took months and months to develop. That is also a reflection on contemporary artistic practices: Some will work quickly and some will spend, maybe two years making a film. That is what we are doing with the show, showing different artistic practices, and everyone has a different way of working through.

ALW: Has the subject of trauma been important for you while preparing the show?

SM: I have not thought about it as a separate thing. But what was important to me was to show those kind of human responses and impacts – I was very keen on having something in this show that would cover the 7/7 London bombings. To acquire and show this film, which is the personal story of a survivor, and how it has affected him, really was important to me. Another perspective I wanted to include in the show were artists who had personally experienced conflict and had to leave their country – Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria – because of it, showing that side of the impact of those war as well. Such as the work "Homesick" (see it here) from Hrair Sarkissian, whose family are still in Syria. It's a daily consideration for him, how that affects his parents and that kind of anxiety that he has. And for us it was really crucial to show a perspective such as from the artist David Cotterrell, who has gone to those war zones, spending time in the medical field hospitals where he recorded the trauma. So I haven't thought of trauma as separate from human consequences, which have always been in my head.

© Jake & Dinos Chapman "Nein! Eleven?" (2012-2013)

© Jake & Dinos Chapman "Nein! Eleven?" (2012-2013)

© Jake & Dinos Chapman "Nein! Eleven?" (2012-2013)

© Jake & Dinos Chapman "Nein! Eleven?" (2012-2013)

Courtesy the artists and Blain|Southern / Photo Vincent Tang

ALW: You mentioned that you started the planning of the exhibition with Gerhard Richter's "September" painting, which itself entails his struggle to represent 9/11, leading him to scrape the figuratively applied paint and to abstract the work. Choosing this abstract work and the extreme opposite, a work by the Chapman brothers that suggests the Twin Towers as two hills of dead Nazis and naked bodies, has the conflicted discourse around 9/11's aesthetic representation been relevant to you when curating the exhibition?

SM: There was a lot of questions around taste – what should and what should not go in, how close we could go with it. I looked at those other works, by Marc Quinn for example, but we decided that these were a little bit too close. Whereas Rachel Howard's painting addresses the same subject in a much more subtle way. Also John Keane did a painting of the tars, showing that image of people hanging out of the windows waving white flags of desperation. But again, I found this too close, so I made the decision not to put that in the show. I also thought very long about the Jake and Dinos Chapman work, and as artists who worked a lot with this subject I thought they needed to be represented. But of course, it cost a bit of controversy. People have somehow tiptoed around this subject, and when MoMA PS1 did their 10-year anniversary exhibition in 2011 they went for a very conceptual approach, and I understand why you would do that in New York. But 16 years on, in London, in the context of a war museum, that has enabled us to be a bit bolder with it, to include those works that are a bit more confrontational. Representing war and conflict is what we do here. People aren't coming here expecting something else.

© Mona Hatoum, Natura morta (bow-fronted cabinet), 2012

Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

© Mona Hatoum, Natura morta (bow-fronted cabinet), 2012

Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

© Mona Hatoum, Natura morta (bow-fronted cabinet), 2012

Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

© Mona Hatoum, Natura morta (bow-fronted cabinet), 2012

Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

ALW: The last chapter of the exhibition, dedicated to the subject of "Home" and personal consequences of war, includes many not so established positions from war affected countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria. Do you think an exhibition has to take a position?

SM: We are an a-political museum, so we are literally reflecting a collection of artists' responses. It was important that there was diversity. For me as a curator there was a wealth of artistic practices from those countries that I felt needed to be reflected in the show. People have been saying though that the exhibition has a very Western perspective, but I think as a museum in the West this is of course where we come from.

ALW: As a war museum you have a different spectatorship than a contemporary art museum. How does that affect your decisions on how you curate a show?

SM: You always think about audiences. About 80% of the audience is not informed about contemporary art, there are many school groups, so it’s about the interpretation of the works and how it is being written. We worked very much across teams in writing that interpretation – it's really not contemporary art language at all. It's very accessible and very clear, making sure that the factual and the political aspects are correct. Working with historians, the text is very accurate, and that's not my expertise. Lots of effort went into the panels; they are all quite short and concise, with a consideration of how the museum visitors would make their way through.

© Omer Fast "5000 Feet is the Best" (2011)

© Omer Fast "5000 Feet is the Best" (2011)

© Omer Fast "5000 Feet is the Best" (2011)

© Omer Fast "5000 Feet is the Best" (2011)

ALW: The four large themes that structure the show are not specified in any aesthetic terms, but rather they bring together themes of reactions...

SM: ...Yes, we had to be quite clear and simplify that language, although if you dig deeper, they are actually quite complex.

ALW: How did those four themes – structured in artistic reactions to 9/11, to state and security, to firearms and bombs, and to the notion of home and personal conflict – come up?

SM: We started with about 12 themes; they were kind of refined over a period of 6 months, selecting pieces was what we were working through the refinement of the themes. In some sense, work that was available takes you in different directions. Because if you can't have a theme but no work to show within that theme.

© Ivan Navarro "Untitled (Twin Towers)" (2011)

© Ivan Navarro "Untitled (Twin Towers)" (2011)

Photo Thelma Garcia / Courtesy Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris-Brussels

ALW: Is the idea of the Contemporary Conflict Team at the IWM to continue organising larger shows with contemporary positions or is it a temporary focus?

SM: The Contemporary Conflict Team is a new team that came out of the restructuring of the museum in 2016 and I joined the museum just after that. I'm the contemporary art curator within a mixes team of historians with different specialisms, we have for example a senior curator who an expert on Afghanistan, a curator of photography, a curator of film, and we currently have an open position for a curator of exhibitions, responsible for larger objects, medals and so on, who will also be expected to become an expert on Iraq. We look more widely on post 2001 conflicts, which had other involvement with the UK, military or things that were direct a consequence of 9/11.

ALW: Will the museum from now on have a larger focus on bringing contemporary art and artefacts together?

SM: It's hard to know that at the moment. Before there was an art team that covered all areas, whereas now we have a WW1 Team, a WW2 Team, a Cold War Team and the Contemporary Conflict Team. Rather than being a separate department, art curators sit in each of those teams, so that the art collecting is being developed within that time team. The IWM has a strong history of contemporary art, we've been commissioning contemporary art since 1917; there is 20.000 art works in the collection. Working with contemporary artists is something the museum has always done, although it's maybe not as known. That was one of the points of the large scale of this show, to push that knowledge out there and make people much more aware of how rich the collection is here and that actually is has been going for a 100 years. In the Contemporary Conflict Team we've been developing our collection strategy for the last year and that includes art not as a separate thing anymore, it's a much more joined up way of approaching collecting.

"Age of Terror: Art after 9/11"

Imperial War Museum London

until 28th of May 2018