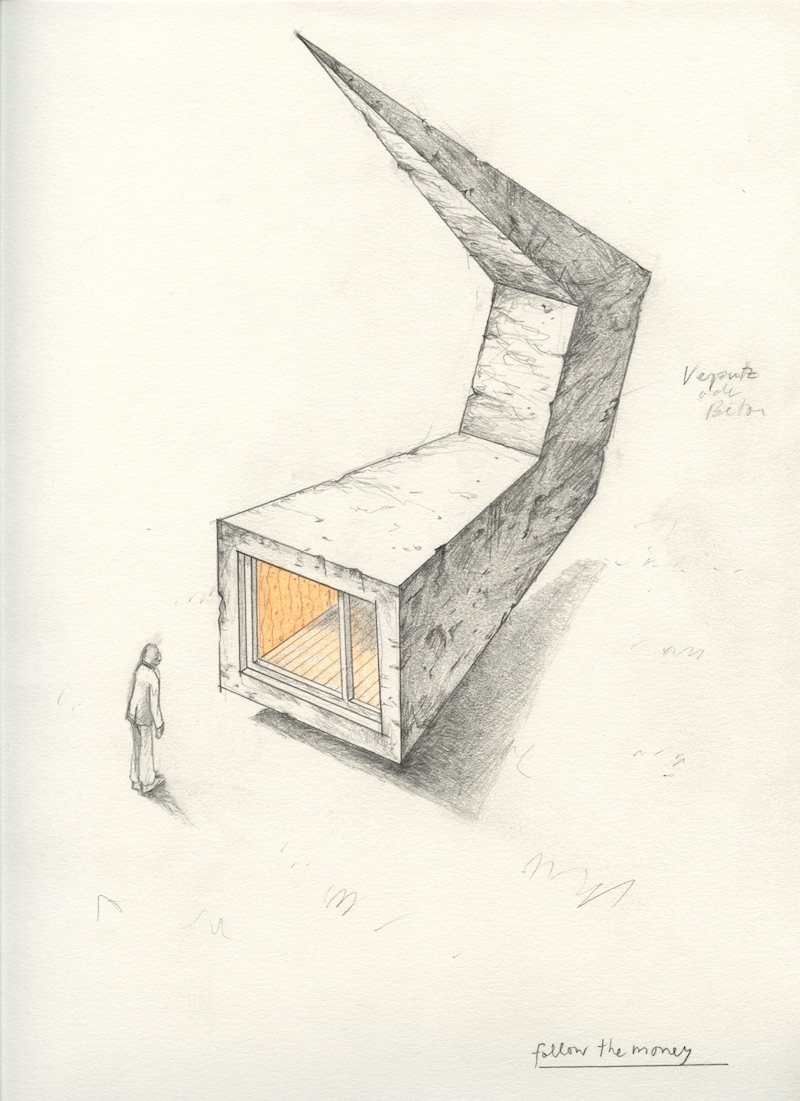

Florian Graf, Verputz oder Beton, Follow the Money, 2009

Florian Graf, Verputz oder Beton, Follow the Money, 2009

Single Page from Drawing Book 90, Courtesy the artist

In his sculptures, installations and works on paper, 1980-born Swiss artist Florian Graf explores the way we install ourselves in a changing and transient world. He creates architectural interventions (and solutions) as well as sculptural environments that allow interaction and dialogue. In this interview Florian Graf talks about his passion for drawing and the plan to show his large collection of Drawing Books.

Lea Schleiffenbaum: Florian, not long ago you told me about the idea of exhibiting your 'Drawing Books'. I believe by now there are more than 150 books in total, originating from your early youth up until today. The sheer amount of books turns an exhibition of this kind into a complex project. Do you see the individual sketchbooks and their contents as central, or do the books instead turn into raw material out of which something new is created?

Florian Graf: Exhibiting books is usually problematic because you can only show one double page of a book when it’s protected behind glass. Having a lot of books makes it easier though. If I open each book, I can already present 150 interesting drawings or collages. Each open page would be a snapshot, all books together would create a rich overview. The main challenge is the selection process, also with regards to a catalogue. The other question is of course the display format. I love to work with space and transformation, and I hope an exhibition and installation with my books will enable something new and unexpected.

View of Florian Graf’s Drawing books, photographed at the artist’s home in Basel

View of Florian Graf’s Drawing books, photographed at the artist’s home in Basel

LS: Building monumental sculptures, platforms for debates, waltzing walls and temples – your work often intervenes directly with our shared public space. A sketchbook on the other hand has a very private nature. The viewing conditions, but also the modes of production between these two practices differ fundamentally. What role do the Drawing Books take on within your oeuvre, and why is it important to you that we as viewers get to know this aspect of your practice?

FG: Drawing is something I do on a daily basis since my youth. It’s not just a passion, it is somehow existential to me. If I can’t draw for a couple of days, I don’t feel good. Drawing and painting also brought me into the visual arts. And the more I started to make sculptures, installations or large scale projects, the more drawing became important, not only as a tool that helped me develop my works but also in order to cultivate a light, playful and spontaneous momentum which can sometimes get lost in the process of big sculptural work. I always loved drawing for the magic threshold between idea and matter. And for some weird reason, the two-dimensional is a great place to think about the three-dimensional. From cave drawings to maps to the flat screen, from disegno to design, there seems to be a crucial interaction between imagination and the material world, even though the flat doesn’t seem to exist in nature.

I travelled a lot during the last ten years, from exhibition to project in public space, from residency to residency, mostly as a lonely cowboy, living a year in Chicago, Edinburgh, London or Rome, spending time in Athens, New York or Paris and making projects in Dar es Salaam, Belgrade or Krasnojarsk. During those periods, the drawing books became a home and often also my studio. Books in general have this homely dimension, you open them and enter. The open book can also be seen as a roof protecting an intimate space. And this intimacy and directness is a very lively thing, a realm where I do things without being controlled or watched, where I experiment, try and struggle. Out of that authentic process I create all my pieces. I always loved to see sketches and drawings by other artists. Often they were more precious to me than the final work.

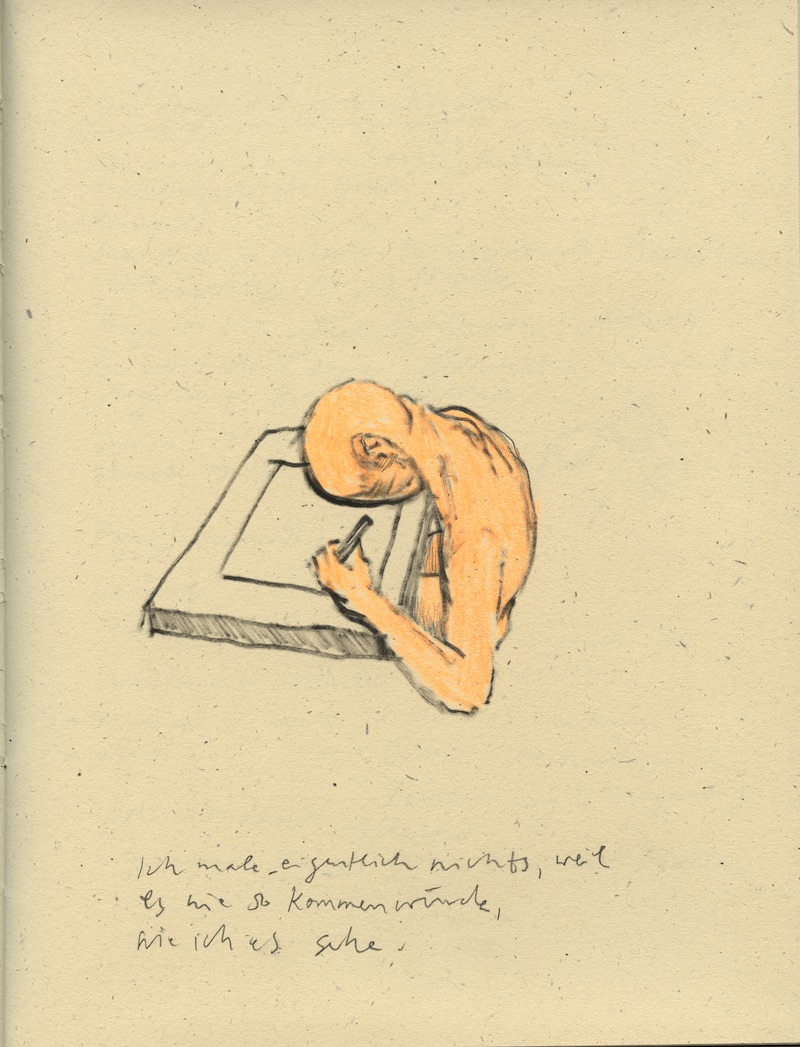

Florian Graf, Ich male eigentlich nichts, 2007

Florian Graf, Ich male eigentlich nichts, 2007

Single Page from Drawing Book 55, Courtesy the artist

LS: When did you decide to assort your drawings into books and what intention did you have in the beginning?

FG: The first serious drawings I made – the ones I consciously had the feeling that I am doing something meaningful while creating them – was during summer time when I was 8 years old. My father is a musician and our family travelled with him to Salzburg where he played and taught during the festival. I started to draw all the churches in town. And not long after that, I started to draw into books. It became a way to connect with the world, with my own world and feelings and at the same time it helped me to feel part of a bigger picture. Drawing and books became a link to different worlds. Therefore, you can always find drawings from observation and imagination in my books. When I started my drawing books I had no intention, it just felt natural, something I like to do. Later on, I realised that the books are valuable to me, a storage of my ideas and impressions, and I can now go back to older books. An initial idea for a piece sometimes goes back many years.

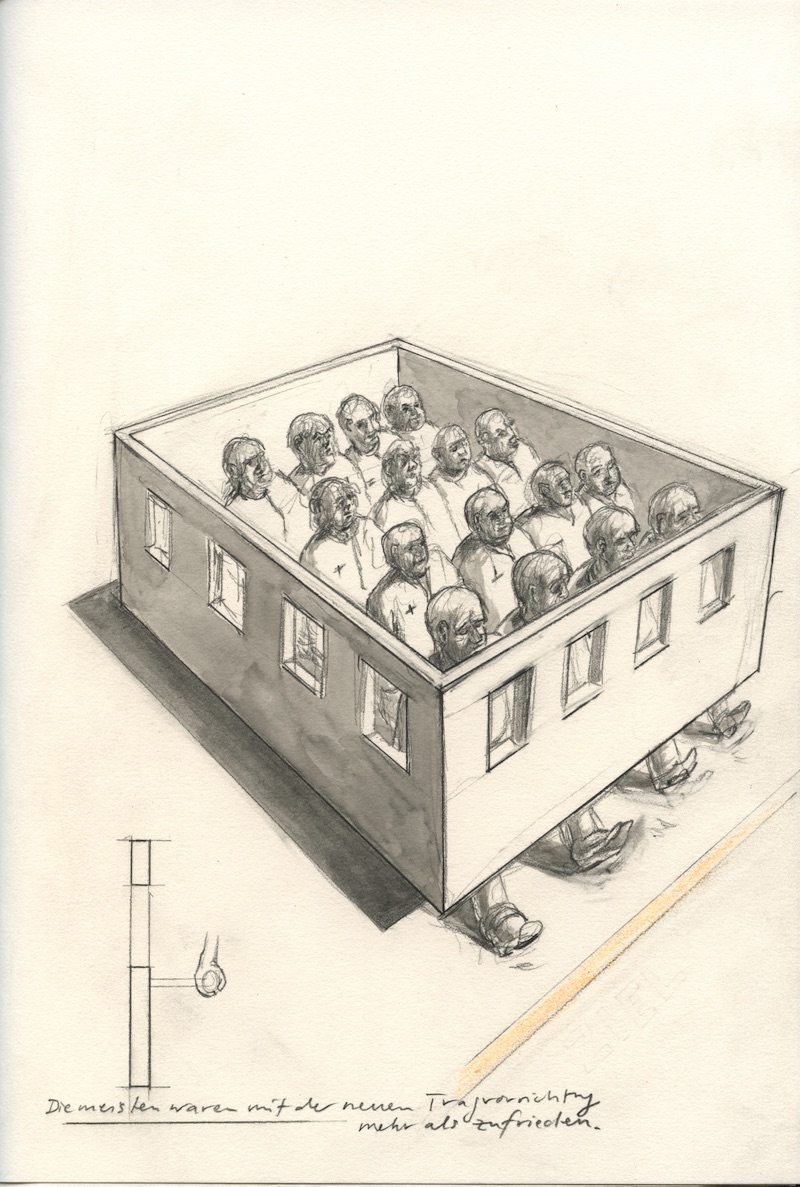

Florian Graf, Die meisten waren mit der neuen Tragevorrichtung mehr als zufrieden, 2008

Florian Graf, Die meisten waren mit der neuen Tragevorrichtung mehr als zufrieden, 2008

Single Page from Drawing Book 71, Courtesy the artist

LS: Did the systematic collecting of sketches and thoughts change the way you draw and write?

FG: I think so. If I make a drawing on a separate sheet of paper, I feel exposed, somehow separated – I am about to produce something to be shown and presented. It feels very different from making a drawing in a book where it becomes sequential. It is more about development and process. It’s about collecting and catching. The single page becomes part of a larger system. When I enter the space of the book I am not afraid of the empty white sheet anymore and I just do what comes to my mind or hand. It is not the making of a presentable work, it is for the sheer pleasure and the urgency of it. The intimate format facilitates authenticity. Thus, the drawing and writing are not about perfection but about continuation and growth, with shifts, breaks, systems and chance, something nature- or life-like.

Florian Graf, Kippenberg (A kind of Fool cano), 2009

Florian Graf, Kippenberg (A kind of Fool cano), 2009

Single Page from Drawing Book 74, Courtesy the artist

LS: The books do not only contain drawings but also your personal reflections on the states of the art, and your role within it. How important is writing for your practice?

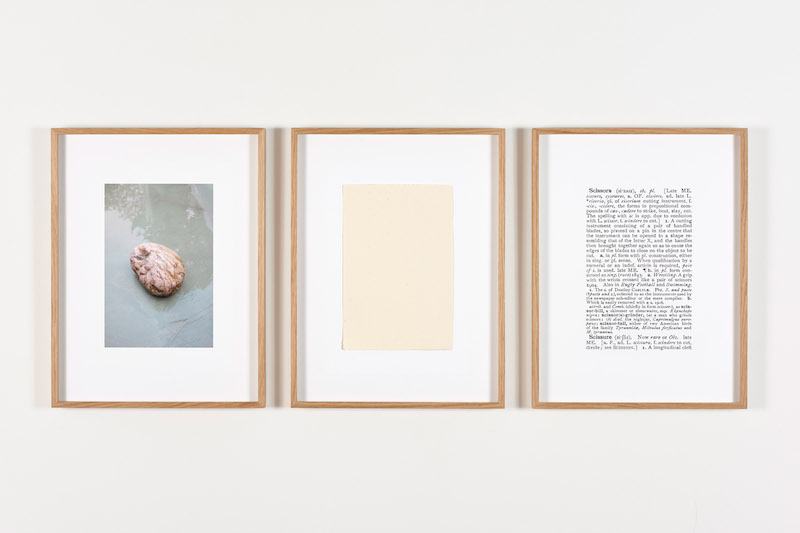

FG: Words were difficult for me in the beginning. As a child, my brain and feelings did not really work verbally. I felt more at ease with drawing and music as ways of communication. Reading was something I slowly discovered. I learned that texts, too, animate imagination, create images and feelings. These atmospheric aspects of words became important to me; they opened up new worlds. I am not a writer though – my writings are mostly thoughts spontaneously put on paper, very similar to drawings and marks. I often play with single words; they become like pictures and sometimes lead to text pieces. Etymology, the history of words fascinates me, and at some point I felt very close to concrete poetry. Something you might find in many of my works is a narrative quality that has the potential to open up to a dialogue. They reflect the relationship between image, matter and narration. Also my titles refer to that. "Rock Paper Scissors" from 2016, for example, directly points out this dependency.

Florian Graf, Rock, Paper, Scissors (Schere, Stein, Papier), 2016

Florian Graf, Rock, Paper, Scissors (Schere, Stein, Papier), 2016

Courtesy the artist and Grieder Contemporary, photo: Gion Pfander

LS: Some of the drawings are sketches for works that you later realised, others seem to be architectural mind-games of sorts. And then there are those drawings that seem to reflect the feeling or the thought of a certain moment. They are often humorous and have a wonderful lightness and directness to them. Can you talk a bit more about the way these drawings come to be? What makes you sit down and sketch?

FG: I draw when I need to find out something that cannot be done by only thinking, or when I want to remember a sensation or a thought. Drawing also works for me as a bait to attract ideas. But the most important thing is that when I draw I feel free. Everything seems open, light and possible. It is a spiritual and sensual meditation that links me to a certain energy and it connects me to a long tradition practiced by artists such as Holbein, Menzel, Morandi, Bonnard, Giacometti or even Kippenberger. I often like art best as a form of thought, feeling, interaction or sensation, and drawing incorporates this very well. In the best moments I can watch myself draw.

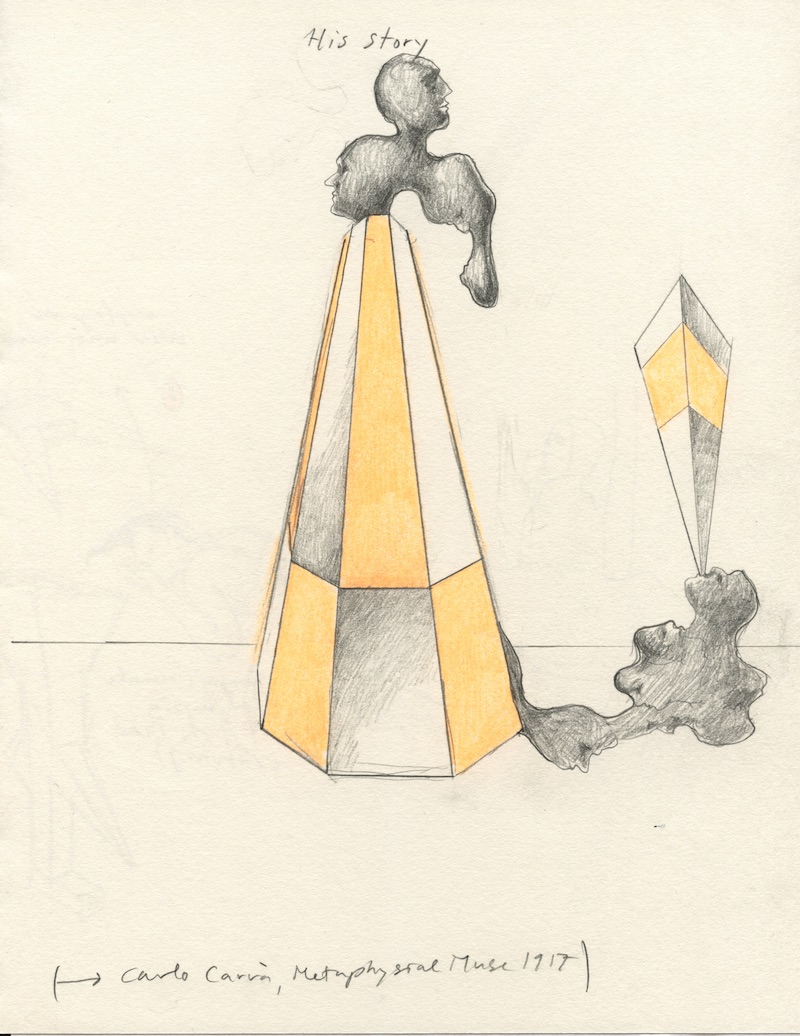

Florian Graf, His Story, 2010

Florian Graf, His Story, 2010

Single Page from Drawing Book 91, Courtesy the artist