all works © Willem Weismann

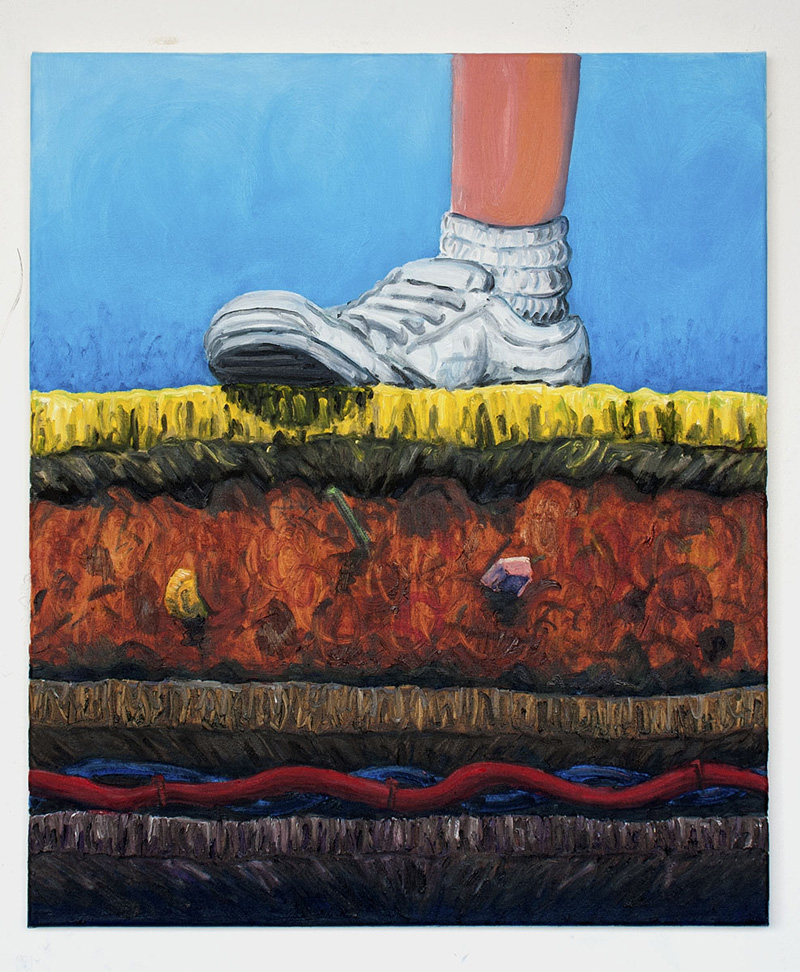

Willem Weismann paints chaos. The narrative scenes that the Dutch artist creates stem from his own imagination. Like stages, they present interiors and extras, revealing layers of flooring, stapled props and set design constructions. In this imperfect world, the perfect façade is always already crumbling. While his paintings often reflect aesthetics from films or even computer games, he returns to the painterly and analogue medium by embedding his entire palette of colours on top of the motif. These could be books, anonym reading figures or simply chaotic interiors, tempting one to get lost in details. Born in 1977, Willem studied at Goldsmiths College in London, where he currently lives and works. His upcoming exhibition "Basement Odyssey" at the ZABLUDOWICZ COLLECTION in London opens the 10th of November.

Anna-Lena Werner: The interior is a setting that you choose fairly often as the frame of your paintings. What kind of spaces are these?

Willem Weismann: I’m interested in manmade environments and my work itself is also a construction, so perhaps that’s why it seems to be a natural fit. It’s like an empty stage that I try to fill up in different ways. Usually I try to keep the proportions as close to life size. That’s why I usually don’t have wide views and landscapes, although they do pop up from time to time.

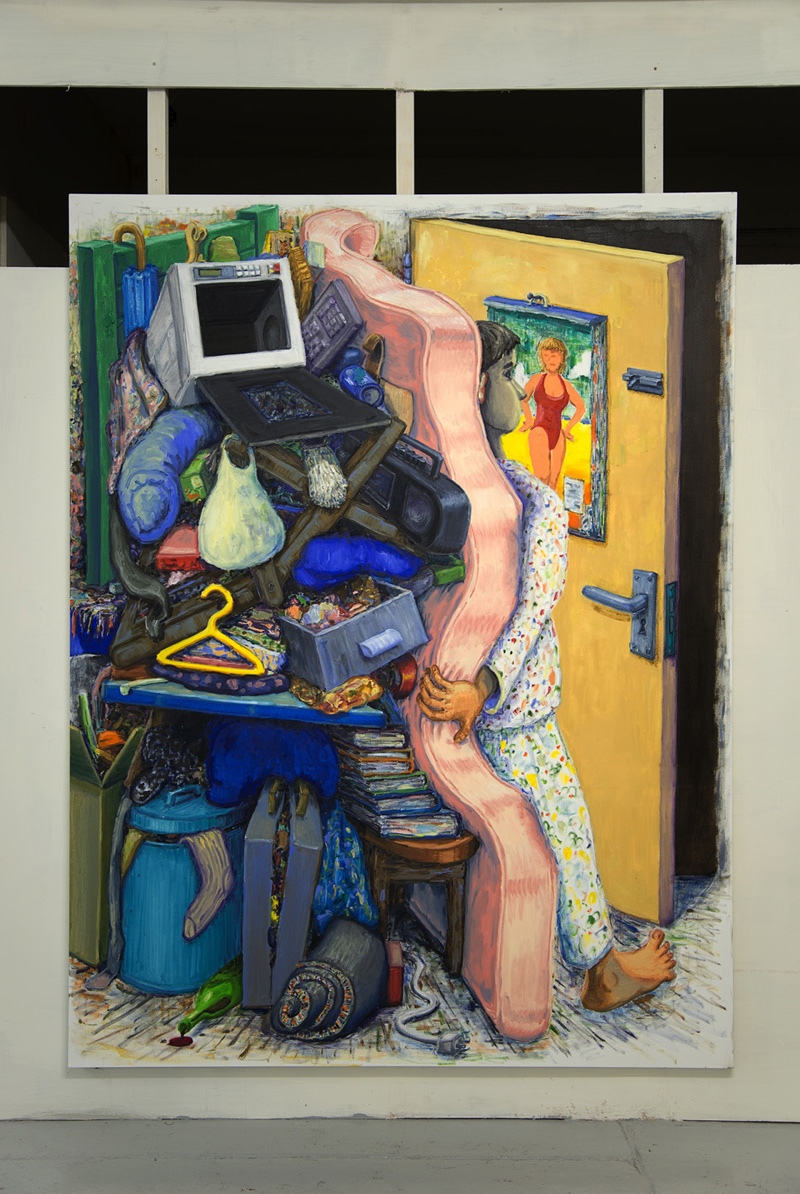

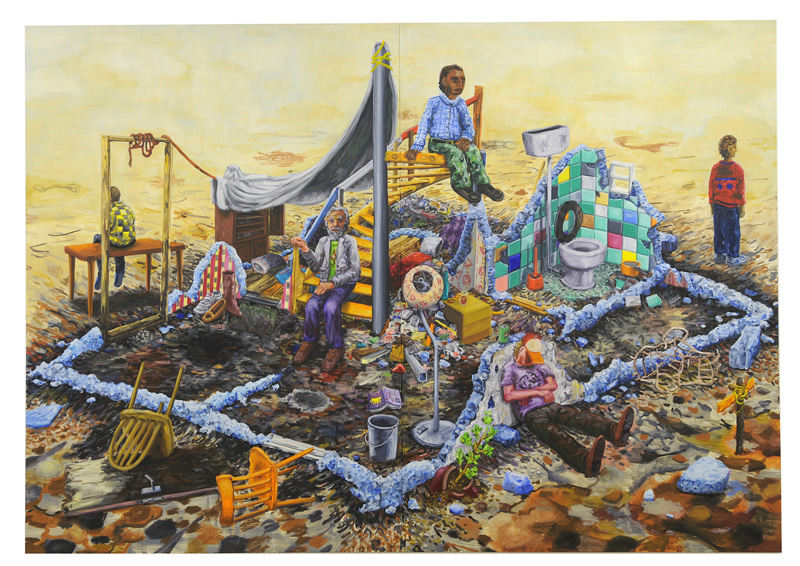

ALW: The interiors are typically filled with items and props, creating a messy assemblage of objects. One painting shows, for example, a man who cannot even move through his door, as he trapped himself in his own stuff that he squeezes behind a pink bed. Is this chaos a narrative?

WW: Of course there is the literal narrative of the man being trapped by his own belongings in an over-the-top slapstick-manner. But it obviously also relates to ideas and critiques of materialism and capitalism. To me personally it also presents the overwhelming experience of browsing through YouTube, Wikipedia and Google and perhaps the impossibility of remembering all one’s own experiences in life. There’s just so much knowledge and material in the world, it seems increasingly difficult to separate facts from fiction and as painter I’m only adding to this pile.

ALW: Is chaos inspirational?

WW: To me chaos seems to be an accurate representation of how I experience the world, so yes in that sense it’s inspirational.

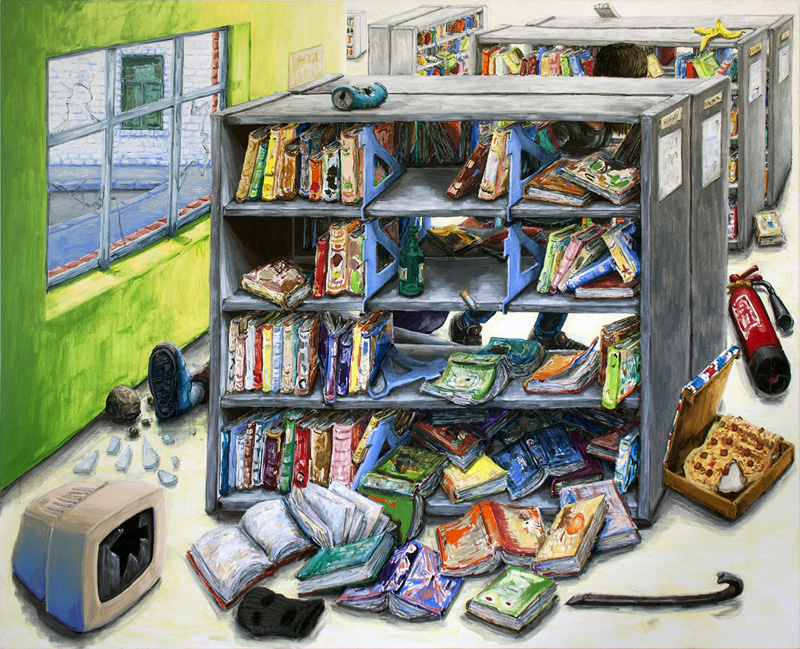

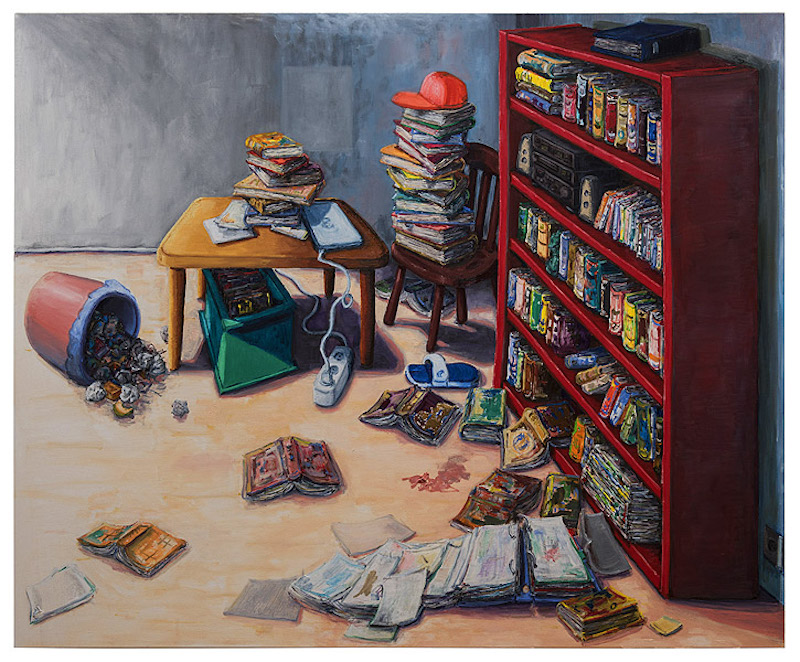

ALW: “Library Looting”, for example, shows a messy corner of a library, in which a bookshelf covers two people who just had a fight. Have you witnessed a situation such as this, saw a picture or do you usually come up with these scenarios by yourself?

WW: No, this is just from my imagination. In this case I was thinking about the library as a public space and how in a similar way to the book, it has lost so much of its importance in the last 10-15 years. It's much more satisfying to make a mess of something that is as carefully and methodically organised as a library. I don’t think it would be on anyone’s list for looting. That’s why I wanted to salute the library by making it worthy of a looting scene.

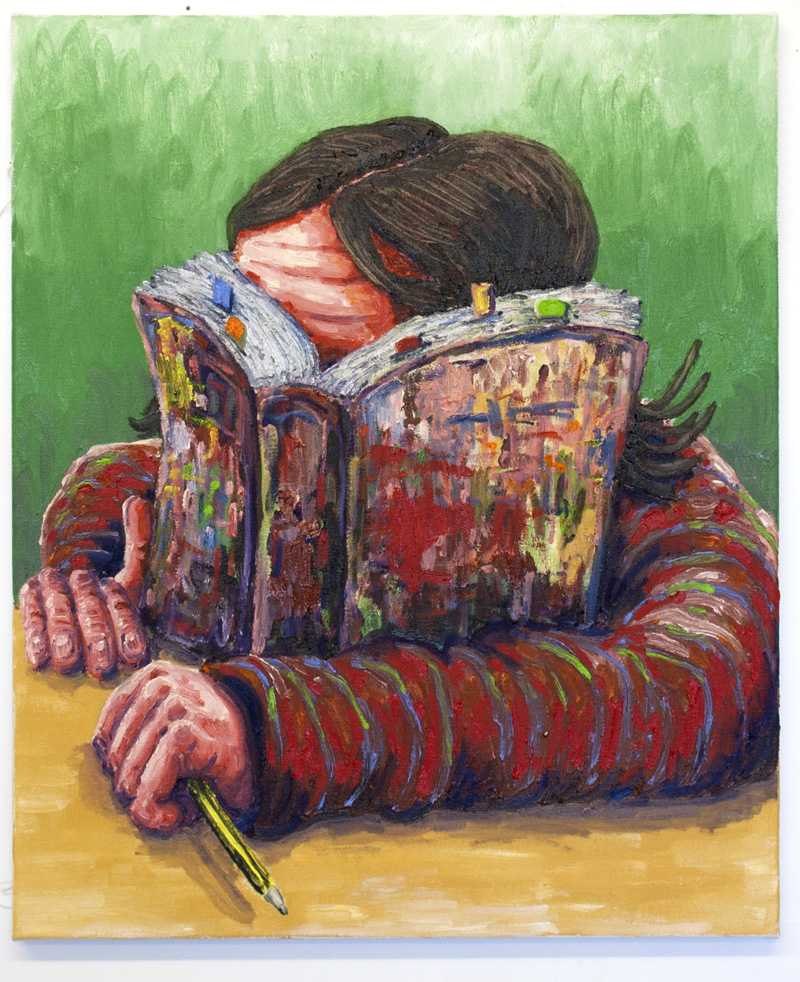

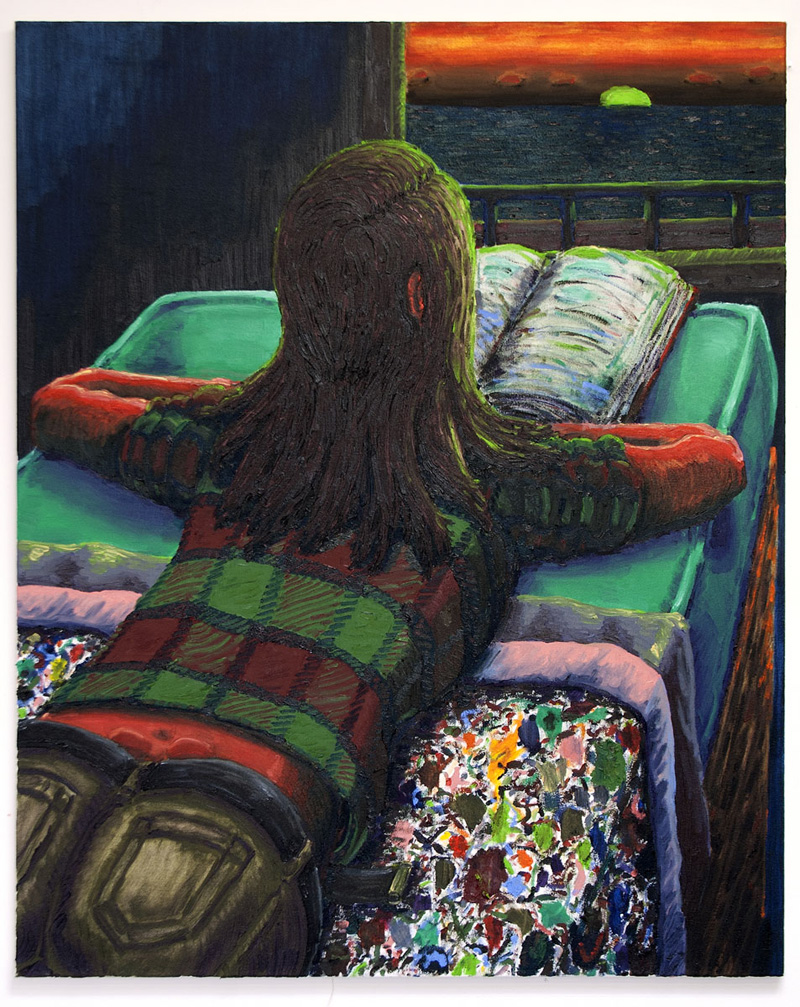

ALW: In many of your recent works you have painted books. They appear both singular, in a woman’s hand or on top of a copy machine and in dozens, crowding bookshelves or library hallways. What is it that interests you about them as a motif?

WW: The idea of the book in my painting went through several stages. First I painted burnt books, for me these were about trauma. The books were like people, and they were similar in size to my portraits. A book burning used to be one of the most shocking acts of destruction. But since so much has now been digitized, these days it's mostly a symbolic act to burn a book. I thought this loss of relevance only added to the sadness of seeing a burnt book. The book then started to take the form of a screen, blocking the person in the painting from being seen and playing with the viewer’s expectation of a normal portrait. They also portray my ideal audience, as they are totally absorbed by the book. This is sort of a wishful thinking on my part, of how I would like people to engage to my paintings.

Similarly, the photocopier also fits in along with the library and the book as an item that was once very useful, especially in a library environment, but now because of digital cameras, also has become relatively obsolete and fallen into disuse. It also refers to being a painter and making a ‘copy’ of the world, and the differences between perfect digital copies, where the copy is identical to the original and analogue copies, where there is always loss of quality or a change.

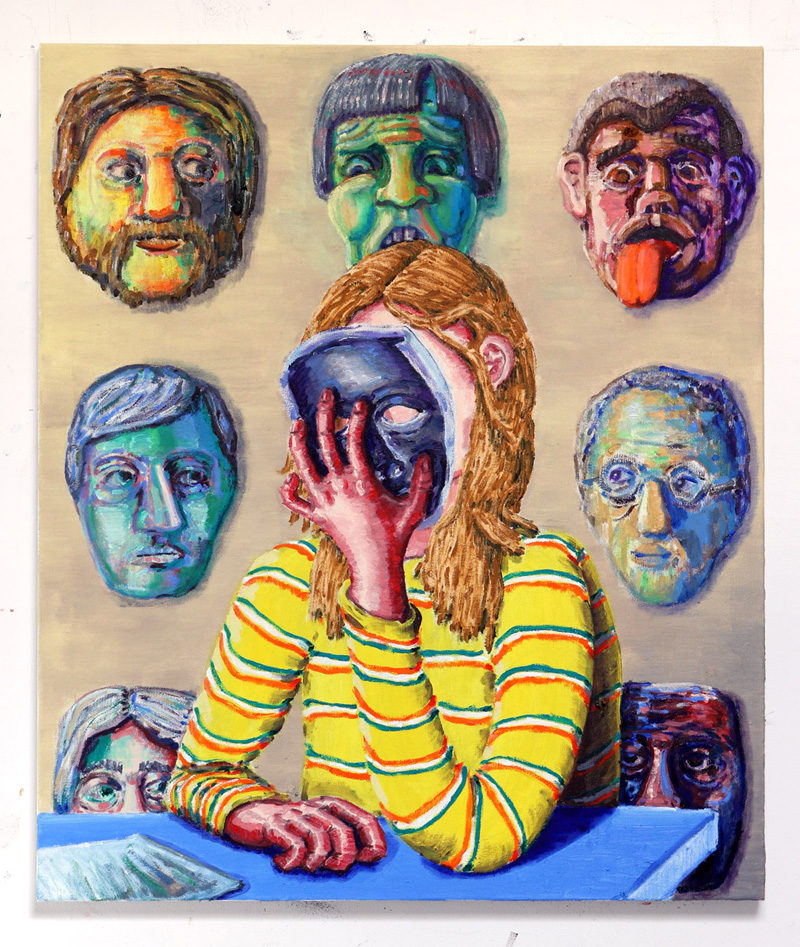

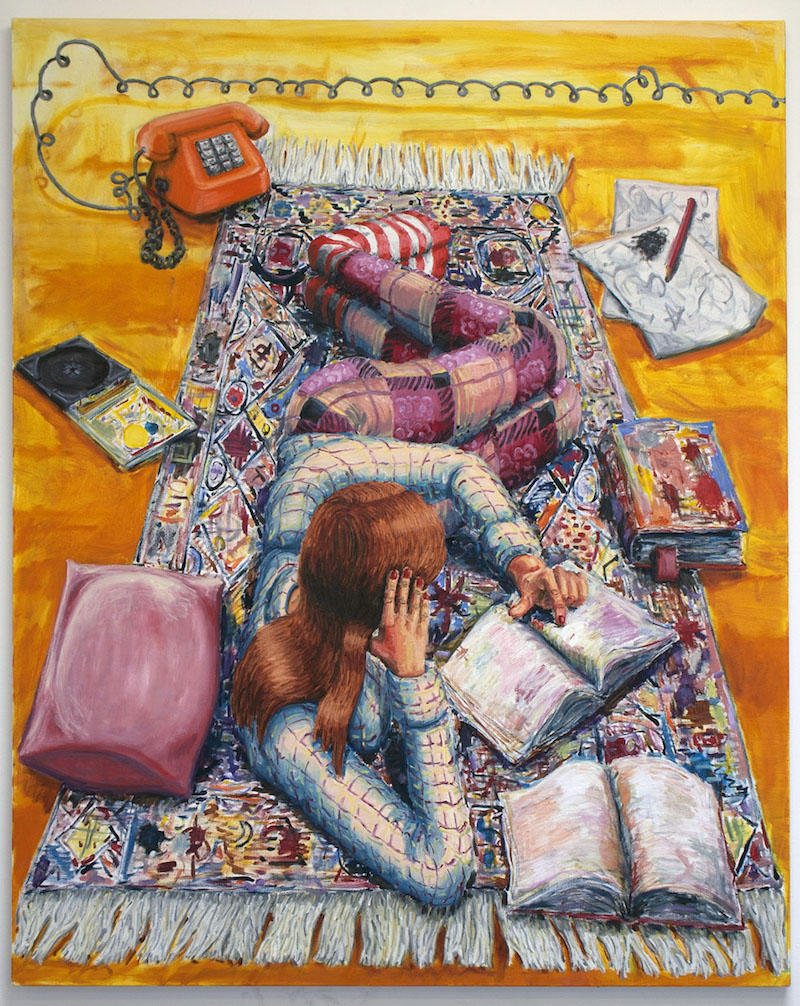

ALW: Humans appear regularly in your works, but they often turn their face away or seem to be occupied, for example by reading. Why are they always half absent?

WW: I used to put a lot of figures in my paintings, and people would always come up to me to ask who they were, as if there were celebrities in a movie. For me the person itself is usually not so important, they are more like extras, it’s more about the scene as a whole. Therefore I started to obscure them, and sometimes literally objectify them by turning them into objects or statues. It’s my way of trying to put them on the same level as the other objects in the painting and not create a distraction.

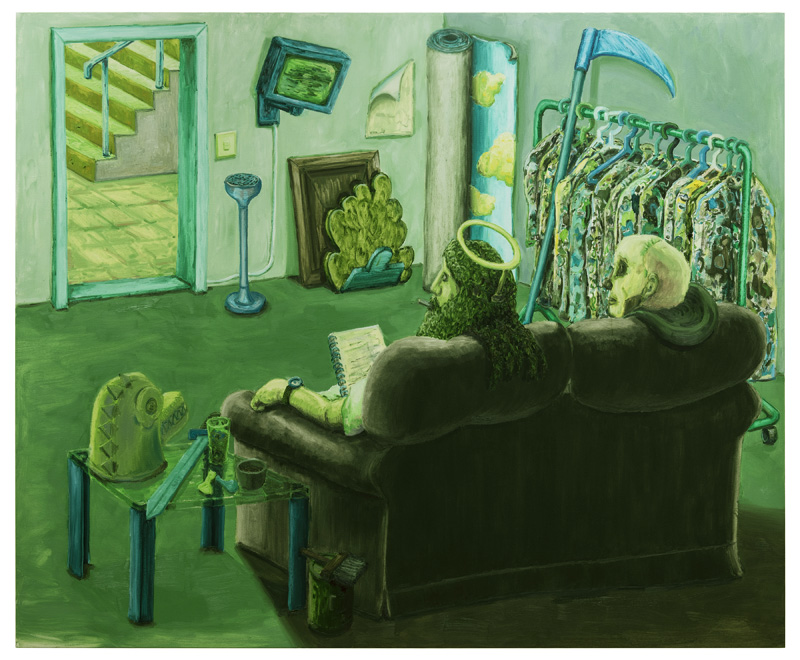

ALW: There is a nightmarish and uncomfortable feel to some of your paintings, I think. "The Green Room" shows Jesus and the death watching TV together, while ”Blueprint” depicts a completely destructed house. Is this an end-of-world notion?

WW: Well, they have quite different ideas behind them. The Green Room is normally the room where actors hang out before they go on stage, or on a talk show. In this painting everything is literally green, a sort of opposite to Matisse’s Red Room. I imagine it to be a look behind the scenes, behind one of my paintings, and in a way my paintings are like a stage set with different items put together in a similar manner. I wanted to make the stage-like construction of my work transparent. God and Death waiting to go on stage – that was also a way to play around with a sense of importance. "Blueprint" is similar in a way that it’s also about waiting. Indeed, there has been a disaster and the people are still waiting to be rescued, the house looks like a raft. For me it’s about people not being able to leave behind the past and letting go of their possessions. Or perhaps at the same time coming together to form a new society.

ALW: There is a resemblance to both, older paintings but also to a certain comic style apparent in your works. Is there a certain type of work that has inspired you throughout your practice?

WW: I think it’s more what naturally filters through from my subconsciousness and is influenced by all what I have seen, liked and aspired to over the years. There isn’t a certain thing I am inspired by, for instance I don’t keep much reference material in my studio, it’s more that I keep trying to tack on ideas from a wide range of sources.

ALW: Do you usually paint as you go, or do you have a sketch in mind beforehand?

WW: I make a very basic sketch of the idea, to figure out the rough composition. The bigger the painting, the more I plan it and I tend to make a drawing with charcoal on the canvas before I start painting. This is usually to outline the composition, everything else I work out during the painting process.

ALW: Strong colours take a prominent position in your work, especially since you typically use one part of a paintings as the palette, while other works are toned entirely in a certain colour, such as green or red. Can you explain what role colours play in your practice?

WW: To me painting is primarily about colours, I always found it fascinating that colour and paint are the same word in German, and how words change how you see the world. I try to make paintings have a physical impact on people, not in an expressive way – that red means anger – but that people can experience paintings on a sensory level before interpreting it. Colour is something that just happens instinctively when I paint. I usually don’t paint in layers, but I prefer to react to other parts that have been painted already, so instead of the image being homogenous there are lots of colours playing off each other, which makes the colours jump out more perhaps. For me it’s another way to express the complexity or chaos of life, that it has not been simplified.

willemweismann.com

Upcoming exhibitions:

Zabludowicz Collection Invites:

Willem Weismann

"Basement Odyssey"

10 November–18 December 2016

The Zabludowicz Collection

176 Prince of Wales Road

London, NW5 3PT

Opening Hours: Thursday–Sunday, 12–6pm

willemweismann.com

Upcoming exhibitions:

Zabludowicz Collection Invites:

Willem Weismann

"Basement Odyssey"

10 November–18 December 2016

The Zabludowicz Collection

176 Prince of Wales Road

London, NW5 3PT

Opening Hours: Thursday–Sunday, 12–6pm

all works © Willem Weismann

all works © Willem Weismann