Visting the Neukölln-studio of 1988-born US artist Billy Rennekamp reveals his intense passion for sports, rules and any kind of game, which he integrates and manipulates in every work that he produces. Balls, sticks, boards and countless props are spread all over the place. The space smells of rubber and leather. I talked to him about material fetishism, the shift from digital to physical art and, obviously, why he is playing games.

Anna-Lena Werner: You grew up in Kentucky. How was life there?

Billy Rennekamp: I grew up on a horse farm, so I love this, like, horse whisperer vibe. My dad is a real cowboy: tall, with red and curly hair, pale and freckly. He always wears a cowboy hat. My dad met my mom in Louisiana – they had this Hippie-Farmer-Lifestyle for a while in Texas. We were four kids. They got divorced when I was two. My mom moved to the suburbs, so I lived between there and the farm.

ALW: When did you leave Kentucky?

BR: I left after High school and moved to New York, to study Film and Electronic Art at Bard College. It was a well-rounded education.

ALW: What made you choose this path?

BR: I think you respond to things that you are good at. From when I was really young I was responsible to fix the camera or the VCR. When I was seven I joined the technology leaders club at school. At College I had this professor – Ed Halter – media theorist, programmer and curator, who showed us the progression of how early avant-garde cinema moved into technology-based practice and internet-art. A website was considered a moving image, the same way film was. There was an interest in surf-clubs, collaborative blogs, and publishing as an artistic form. I was following all these video artists working with the Internet. In 2009 I received a grant from my school to assist Oliver Laric in Berlin. After that I commuted between New York and Berlin. And since 2013 I have been here permanently.

ALW: Was the move also related to your shift of making digital to physical art?

BR: I guess it was a little bit. At that point I was still based in electronic arts. Also for the convenience, in terms of carrying around a studio, making work as a practice is much easier if it’s based on your computer. I also lost some of my actual possessions in that period, because I was moving a lot at the time. It was somehow around the time that I moved here, that I wasn't making many physical things. With the electronic stuff you are able to produce things without having to pay for anything. It’s a cheap and theoretical way of building material. You can make a sculpture in a 3D render program, and you wouldn't have access to the material or wouldn't need to build it physically. In 2011 Timur Si-Qin did this project called 'Chrystal Gallery', in which he asked people to send him 3D objects and he rendered them inside of a real looking gallery. On photos you couldn't tell that it was rendered. A couple of years later a collector called me and asked if that piece was still available. And I said no, but that I could produce it, which I did. So it is actually on display in Dublin now at his space Ellis King.

ALW: You were in several collectives.

BR: Yeah, we had surf clubs and collaborative blogs with Petra Cortright, Travess Smalley, Eric Mack or Hayley Silverman. The blog is still there but it really slowed down since tumblr was invented. We did physical exhibitions as well, finding out about the digital art world through that. It was all about meeting people. At one point I felt like I could travel to any major city in the world and I would have a random friend from there.

ALW: Do you consider online communication a positive development?

BR: I think its exciting, like developing a language almost. You are part of a new form of communication and you get to define it as you go. Texting has all these parallels to spoken language. Like, LOL – it’s an emphatic pause. Purposeful mistakes, misspellings, and so on. I am more expressive in emails. Right now, when I speak, I am surprised to have words come out of my mouth. I don't really know what I am saying.

ALW: Really?

BR: Yeah! I remember getting really mad at a professor once, when I had a conflict with him. We had to have a debate and I thought it was unfair that we couldn't do it by email, where I could collect my thoughts and defend myself. I though it was unfair to speak in person in real time.

ALW: What's your favourite form to communicate online?

BR: The group chat. My own little private social network. Its much more fluid and honest.

ALW: Are you sometimes sceptical about the Internet?

BR: I am not so dystopic when it comes to the Internet. I think there is a need to be; there should be a backlash against it so things don't get out of hand. But I am not providing that. I was frustrated for a while that I couldn't find a non-dystopic sci-fi scenario. When 'Avatar' came out, I just wanted National Geographic to go to Pandora – this is obviously an amazing world. But I don't want these characters, this narrative. I just want to be in there. But I might have found one recently with 'First and last men'. I didn't realise before that there is a genre called future histories. It was written in 1931, describing the world's scenario in the future.

ALW: You once worked for DIS magazine...

BR:... I did an internship. For a while a thought that was the best thing in the world.

ALW: Until you realised that there was no money in it?

BR: No, I thought that's what is great about it. I was able to make money programming on the side for a long time. With extra time, energy and resources, I felt like I could donate that to a cause that you were interested in. Like: 'I support you. I want to give you my resources and skills.' I also worked for Cory Arcangel and Rhizome. It was never about money.

ALW: And yet, you have now stopped to make digital art and changed to physical art. Where did that come from?

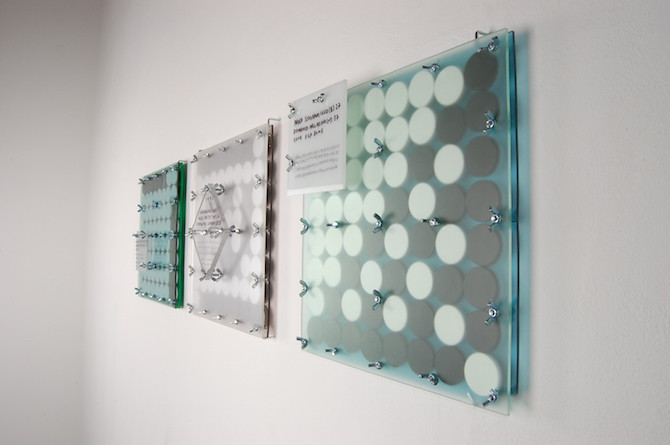

BR: I think that came for a few different reasons. One being the community of the Internet art world expanded to a point where I didn't really feel like I knew everyone anymore. Also other artists were maturing in their practice, having a desire to make something physical. Since I was programming for money, it felt weird to program for art. I had this mental separation. I wanted to be more physical when being creative, so I transferred this interest in systems, structures and software or rule-based world making. It came from video games; it’s a kind of miniature world with your own set of rules. I was wondering about these rules, creating them and wondering what would happen if you would break them, so I applied that same logic to the physical game, physical interaction, and sports. It seemed like a seamless transition. As if the sports were like a physical version of software. A set of rules manifested in the physical world. So it was a combination: A loss of touch with what felt like an intimate community as it expanded and a desire to be physical. My works fulfil a physical desire; I want to touch these things. I have to make the object, so I can be with it. It’s really satisfying to be able to touch it afterwards.

ALW: I am sure that this is a kind of object-based fetishism that many artists are driven by. The product from a handcraft. Is that missing in the Internet?

BR: Well, I'd say that programming is very much like a craft-based work. But if there is a digital object, there is still this desire to touch it. It becomes heightened: the sexier the object looks while it’s physically out of your grasp. It’s an ideal version of a thing. That almost makes it more exciting.

ALW: I find the emphasis on materiality striking in your new work. For example, the one in which you stretched basketball material on a frame.

BR: That one really makes me want to touch it. It looks like a pregnant belly and the title is TBA, to be announced.

ALW: Where is the material from?

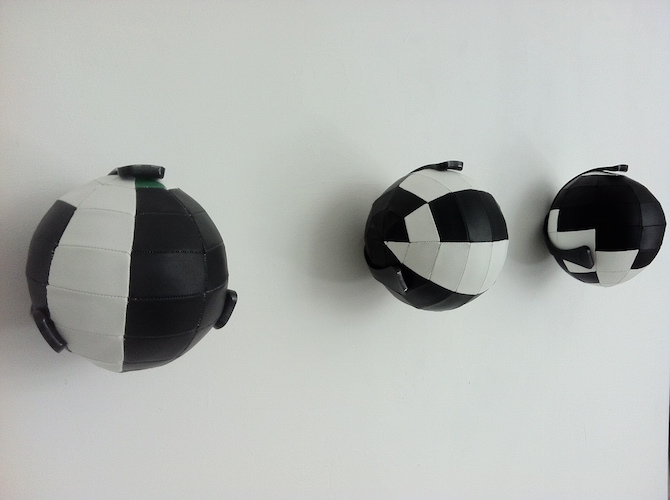

BR: I get it from a distributor in LA; they produce it to make furniture out of it. For children’s bedrooms, for example. These are synthetic, but the black and white ones are leather.

ALW: Do you encourage the audience to touch your objects?

BR: I guess they could, but I hate the idea of people touching them, because I don't really know who they are. Whenever you have public art or interactive theatre, it makes me cringe. It’s kind of cheesy.

ALW: Why such a focus on sport materials?

BR: They are super functional. They are chosen because they are abstracted to a point, it’s easy to understand, easy to use. They have a friction to them. They have solid, primary colours. All of these things are really functional with sports, because they make boundaries apparent. It’s beautiful to have so much function in an object, to reflect that. They represent this boundary between the physical and the ideal of a rule-based world. Super sensitive objects. They are made to be touched, so there is this fetish part as well.

ALW: Why is there dirt on the black and white wall-object?

BR: I stitched it together and used it as a sled on a hill. Messed it up. The inevitable failure of physical work coming from a digital perspective. Whenever you make it physically, its obviously not going to be as perfect as it was in your 3D-file. I wanted to embrace that fact and push that aspect, by physically pushing it around.

ALW: Do you mostly focus on Basketball, Polo, Rugby and Soccer?

BR: No, I feel like I collect sports. I collect shapes and ideas that are interesting. And later they might even fit together.

ALW: What about board games?

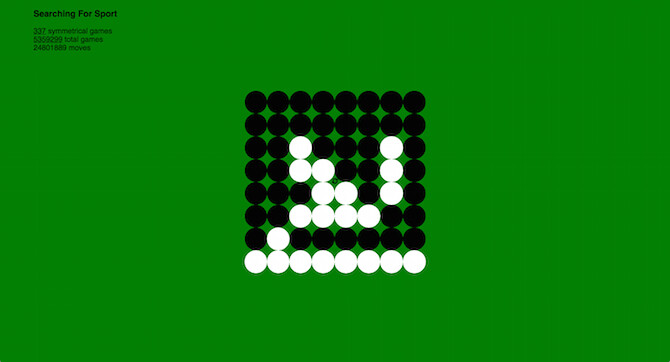

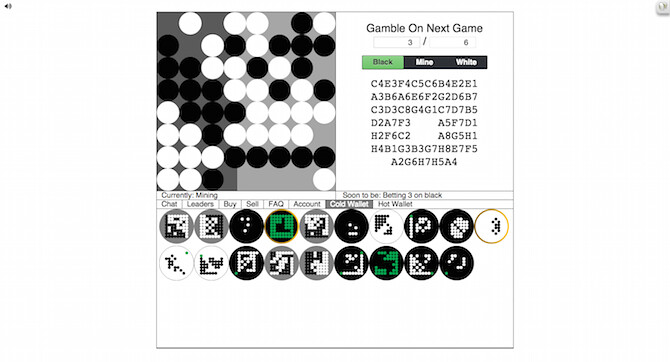

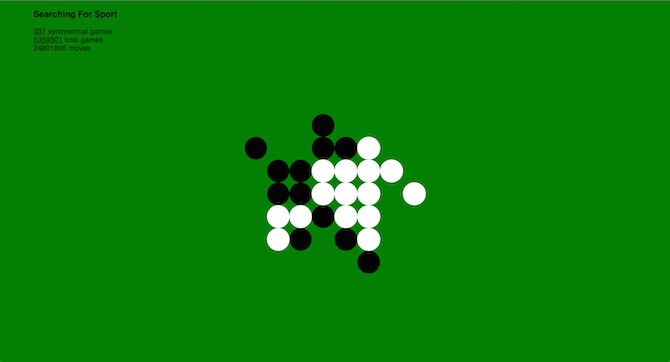

BR: Also. Specifically the game Othello. It came from school, where I took this cognitive science class. One of the assignments was to build a game that had a computer player. So you design a set of rules and heuristics for the computer while it’s playing against you, so that it will win. The computer looks at all the possible moves and sees which one is most beneficial. There are different methods to improve that. I wanted to find out if its possible to play the game so that the final board state would be symmetrical, which ended up being really difficult. The game tree is gigantic it would take forever. I had it run for a long time and found six or seven of these symmetrical games. It became this hobby of mine to find symmetrical boards.

ALW: This project is kind of complex, don't you think?

BR: I think of it as my artistic dad-basement-project. I don't even know if I look at it as art work or not.

ALW: Its design looks really great.

BR: My whole interest in the game is visual. It’s a really beautiful game.

ALW: Are you good in playing Othello?

BR: I was playing a lot, trying to be good at it. But you have to memorise a lot of things. It’s really big in Japan. Every town has their own tournaments; it’s a big deal. The French players are traditionally really good but the Netherlands have been winning the big tournaments recently. I reached out to the head of the German team a while ago, Matthias Berg, who had just moved to Berlin. He was excited to have someone in Berlin interested in the game and convinced me to come to some meet ups and tournaments. He was really amazing because he’s been the German champion for 10 years or something so knows all the great players and introduced me to them. I played in the German national tournament, and due to scheduling conflicts of the other players I ranked high enough to compete at the World Championship in Stockholm. I love running across names of players I met in real life when I’m parsing tournament records for the project.

ALW: What are the hands about?

BR: They are collages of different sports logos from professional American teams. It was a similar desire to work with the logos as it was with Basketball or Football. I feel attracted to them physically or visually. I was able to get these vector images, which are a scalable version of an image. The hands are based on a format of the foam hand. I went through and made 32 of them, which is every possible combination of having a hand with different fingers up. It’s like a math teacher's thing to show you how to count in binary. I like the idea of exhaustive search. The fact that I have access to the digital SVG file means that I can go through every possible configuration. Digital storage is cheap, so you can store every possible scenario.

ALW: You are not so much into sports, as you are into games?

BR: I'd like to think that am into brains! Computers are a nice way of using brains, an extension or a facility. Sports are where it bubbles up to the surface.

ALW: I have to think about muscle memory when looking at your work, like a coherent choreography. Its absent or reduced in non-physical, digital activities, as opposed to its presence in sports.

BR: Yeah, I think that’s how brains work. They create patterns of events or connections, and if they are stable, they reinforce them over and over again. But what I really love is when they break. Jeff Hawkins, a brain researcher and also the inventor of the Palm Pilot, has this model of the brain called the memory-prediction framework. Not only do you build pathways and patterns, but also you rely on them, in a way that you ignore the world around you. You predict what's there, because you expect it to be there. There are different versions of this, like, when you walk, you expect the ground to be there. The only time when you notice the ground is when its not there, when you fall. Then you have to think about the floor and rebuild your model of the world, instead of predicting it at every moment. That’s when you make a new neuro-pathway. Then you have to update your model of the world and you'll get a more accurate version of it. Disasters also change perception. I think people can get addicted to the “new” like that.

ALW: How important are the sport's figures, like the fans and the players for your practice?

BR: The players are important as material in the game, they are like idealised and streamlined versions of humans. I would potentially work with them in that manner, because I think they are beautiful. Fanwise, I like the idea of fans creating gravity around and towards the sport, and also as materials. They are necessary but always on the outside of the magic circle. They even elevate that magic circle.

billyrennekamp.com

billyrennekamp.com

all works © Billy Rennekamp