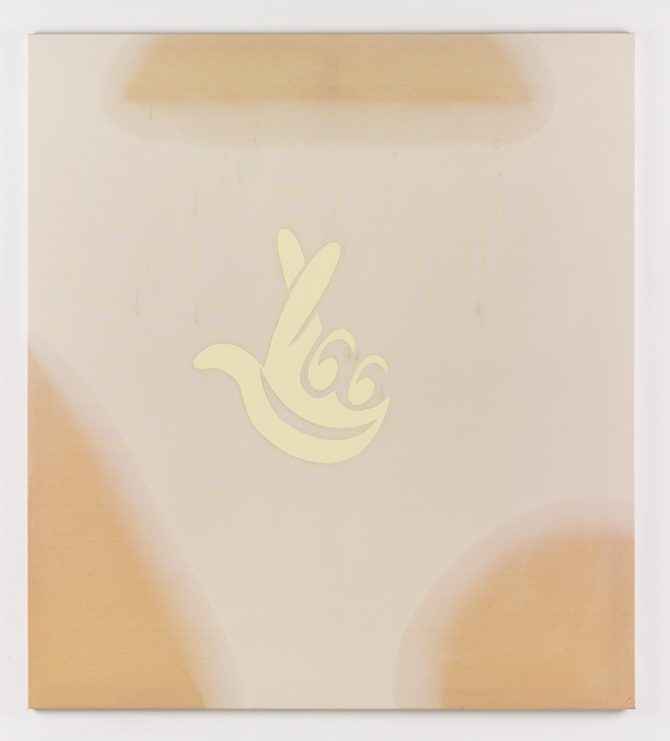

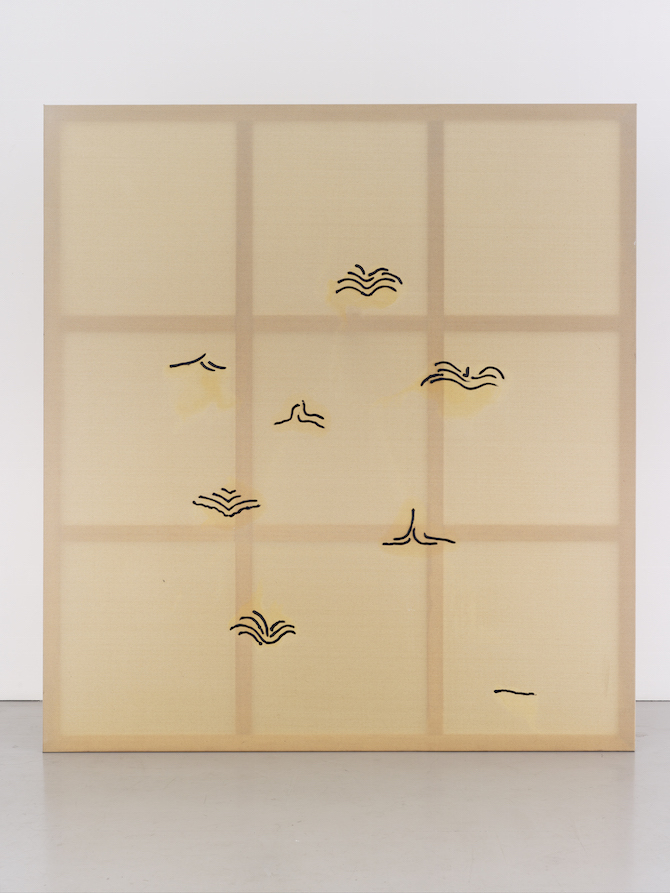

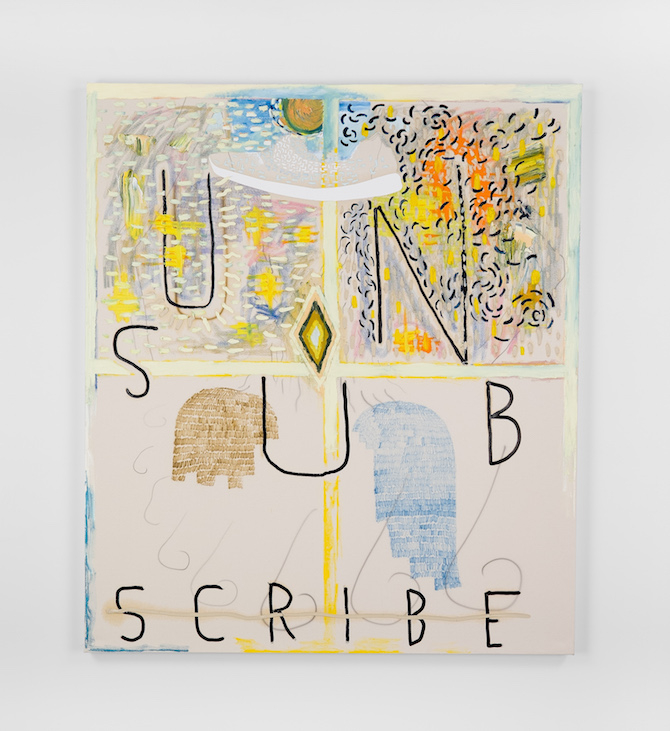

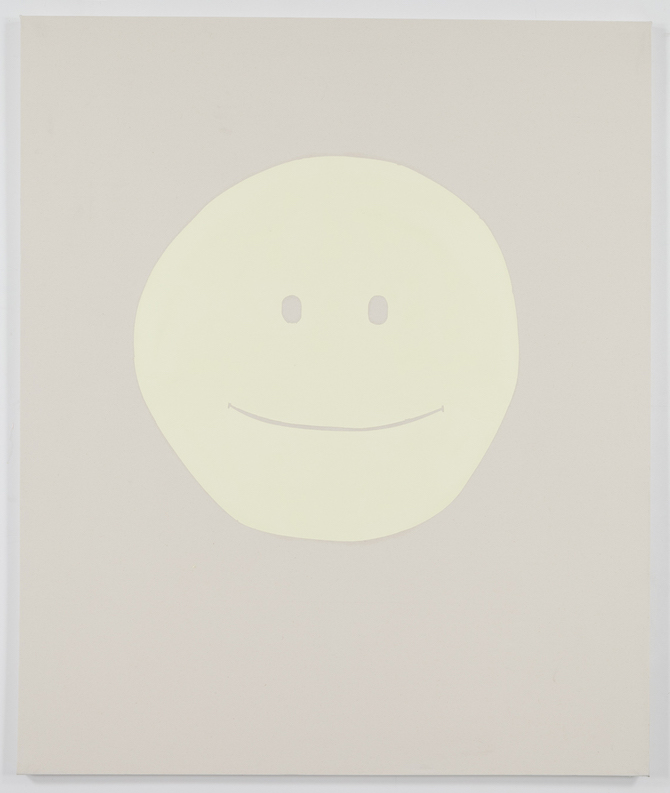

all images: works by Florian Meisenberg, © Florian Meisenberg, courtesy the artist, Kassler Kunstverein and his galleries Wentrup, Berlin; Simone Subal, NYC; Mendes Wood, Sau Paulo; photos by Joerg Lohse, NY; Sebastian Bach, NY; Anna Arca, London; Trevor Good, Berlin; Nils Klinger, Kassel; Bruno Leão, São Paulo; Gui Gomes, São Paulo

all images: works by Florian Meisenberg, © Florian Meisenberg, courtesy the artist, Kassler Kunstverein and his galleries Wentrup, Berlin; Simone Subal, NYC; Mendes Wood, Sau Paulo; photos by Joerg Lohse, NY; Sebastian Bach, NY; Anna Arca, London; Trevor Good, Berlin; Nils Klinger, Kassel; Bruno Leão, São Paulo; Gui Gomes, São Paulo

The offline and the online world merge with German artist Florian Meisenberg. Using the media of paint, performance, installation and video, his work reflects the variety of skills that he experienced throughout his life: Florian first studied media design, until he eventually entered the art academy in Düsseldorf and studied with Peter Doig. Whilst being intensely sincere about formal and critical concepts behind his work, he openly discusses what moves and motivates him.

Originally born in Berlin in 1980, Florian moved to New York in 2010 with his girlfriend and collaborator Anna K.E., who also studied at the art academy in Düsseldorf, since then sharing a studio in Bushwick. Not only a team in private life, Anna and Florian often create work together and approach each others practice both aesthetically and conceptually. But also from a more general perspective, the subject of intimacy is a coherent theme in Florian’s work, expressed in both physical and digital relations of beings and objects. While his unique instalments and performances, for example at Kassler Kunstverein or Kölnischer Kunstverein, often relate to the composition of screens, appropriating a digital aesthetic of pop-up windows, manuals and simultaneous data-streams, his videos incorporate corporeal affection.

Over the course of half a year, Florian and I messaged each other questions and answers, discussing his practice between the digital and the analogue, his fascination for the Internet, for exchange and for digital jet-legs.

Anna-Lena Werner: Florian, I saw almost all of your vimeo-videos during the last days. Would you say that I know you better now?

Florian Meisenberg:

ALW: When you graduated at the art academy in Düsseldorf in the class of Peter Doig you were a painter. Why did you start to incorporate video art in your practice?

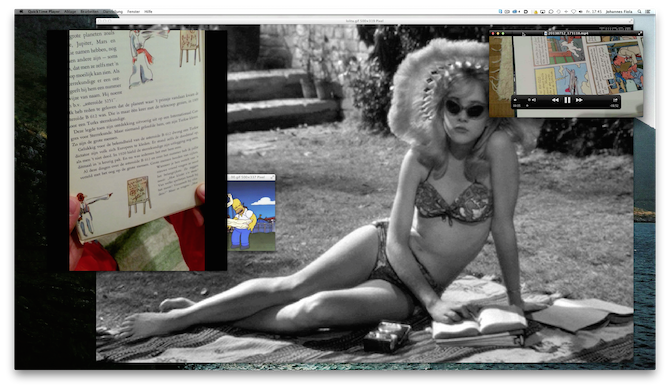

FM: The medium film fascinates me, as it allows me to capture everything that comes to my mind, instantaneous and without big preparations. From the beginning on it also served as a tool to involve and question the creative process as such. This fascination, to expose the process – to promote it into a self- sufficient artwork – never let me go. While I slowly transitioned from sites and readymade environmental sets, as a stage for my performances to the digital sphere, the computer desktop and screen capture program became the tools and stage of my choice. The very first film I ever did was shot in a residency at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine (rejected application for a professorship at the academy of professional conceptualism) – actually still during my time at the academy in 2009. Here are more recent examples:

and

and

ALW: You refer to your paintings as 'screens' and your exhibition installations sometimes remind of the composition of a computer desktop. How do you differentiate the digital and the analogue in your art? Is there a hierarchy in their relevance?

FM: In my painting practice, I attempt to utilise all capacities of the medium painting in its full spectrum. Painting engaged over centuries with an abstract existential philosophy communicated in hundreds of different self-developed languages and served simultaneously as a black box for our entire human history. Thus, the medium of painting appears to me as the ultimate human agent, to evaluate contemporary conditions with a focus on the virtual and digital sphere. Especially now, in times where we seem to loose sight of ourselves and the very basic necessities of being human - hypnotised by the digital revolution and the unstoppable advancement of technological based western capitalist progress.

A blank screen can serve as a mirror. Once the screen ceases to stream this infinite amount of information and images, and we eventually see our face reflected in the dark, blank screen of our smartphones - we finally become aware of its qualities as a mirror reflecting ourselves. I think that we are mesmerised and kind of hypnotised by the tremendous amount of phenomena the screen is transmitting to us or rather, that we are able to choose from. As we are users now, not simply viewers anymore, we seem to forget to engage with some very basic existential features of active self-reflection and criticism. Also, I feel the internet already serves as a temporary memory extension but almost none of the data will eventually be processed, to become part of our minds. Reflecting on that, we already live in a kind of hybrid exchange with the network.

Myself included, I am specifically fascinated by the idea of the Internet being an ultra collaborative machine. I am interested to explore existing and to create new utopian architectures of collaboration. In my installations, I tend to set up a sort of experimental testing ground, a hybrid space, dislocated between the digital and analogue. They are two entirely different spaces: Firstly, my studio, a highly private and intimate place of dense subjective time, sensual and psychological and energetically transformations. As opposed to, secondly, the vast open-ness, the chaos, the hyper-frequented interconnectivity and the seemingly endless possibilities of networks in the digital world. I like to observe how these different spheres stare at each other, threaten each other, how they collide and intertwine. It is seeing how data or images are altered between the spheres, sometimes becoming obsolete and sometimes more meaningful.

ALW: How significant is the material of paint to you?

FM: Oil paint literally represents human substance, not only as a concept, but also within the history of being and becoming. Historically, oil paint was invented to imitate the haptic and albedo of the human skin in early portrait paintings. For me, it never lost this reference. This proximity to us enables the medium of painting to summon an incredible gravity, which re-joins with the infantile energy inscribed into the memories of our first attempts to communicate.

ALW: Your videos show you wanking to an iPhone commercial, singing, quoting or holding a lecture about Nietzsche in front of some cows. A girl's naked toes keep on reappearing. How are philosophy, poetry and sexuality related in your work?

FM: Once the metamorphosis of becoming commenced, independent fields of notions disappear and there remains only one unknown horizon:

ALW: What does intimacy mean to you?

FM: I would say that intimacy is mostly a human feature, or it mostly exists in a human context as a construction or projection in our minds. I would suggest that intimacy occurs in the constellation of different parameters and their relation to each other, like time, space, sensuality, sensibility and tangibility. These features mostly resonate between two subjects – like human to human, or human to animal – or subject to object – like human to car, jewellery, cell phone or computer. So, the shift of paradigms that we are experiencing from the industrial to the digital revolution, moves from the classic form of intimacy between two subjects to a predominant and almost fetishised intimacy of subject to object. And the future already started to introduce other forms like object to subject – robot loves us – or object to object – robot love. I would say that intimacy is an important aspect and simultaneously a proof of any sort of human relation and engagement with the world, but also with conceptions.

Since most of these features are abandoned or exists only under completely different terms digitally, I feel we have not been able to discover or even simulate adequate structures of intimacy in the digital sphere, causing several symptoms: Besides our temporary memory extension via the internet, there is a vacuum of trust created by the absence of intimacy within the internet. As trust is one of the premises for any sort of exchange – of course, social exchange, but also business and any sort of creative exchange, it is hindering a more open and transparent usage of creative forms in the internet. This is cutting off its powers of serving as an open and shared mind, fed and used by all simultaneously: clouds of man and machine, beyond regular, worldly and physical limitations.

ALW: For the Liste Art Fair in Basel you recently created a number of collaborative works with your girlfriend Anna K.E. How does real-life intimacy affect your creative process?

FM: Anna and me share a studio since we moved to New York five years ago. In many ways our creative processes are intertwined, reflect and complement each other - like an infinite mirrored mental space, that we share life and work in. It is very beautiful, some times really intense but always very fruitful.

This situation became the ground for our recent collaboration, the project "Late Checkout", with Simone Subal for Liste Art Fair in Basel. We conceived the concept and worked on it together from the beginning to the end. For "Late Checkout" we did several paintings together: digital sketches, collected from my phone, and translated to bed-sheet like fabrics. We also created a series of new films, all shot in different luxury high-rise Hotels across NYC. Always confronted with the same setup: a small, isolated room in a new condo building, with one gigantic wall of windows. Trapped behind a 'screen', in a vacuum of a room, we manage to get almost enough space between us, to conduct a choreography of intimacy via the screen - as the camera that I control is wirelessly connected to the smartphone Anna is keeping. Broadcasted in a live-stream, she sees what I see, classical roles are overcome and we melt into voyeurs of ourselves – via the screens, ultimately connected but always apart, we become silent actors, enacting a muted script to the rhythm of the unimpeachable air-condition.

In the fall of 2016 we will have a collaborative show at Signal Gallery in Brooklyn, extending 'Late Checkout' into a full scale installative environment.

ALW: For the Liste Art Fair in Basel you recently created a number of collaborative works with your girlfriend Anna K.E. How does real-life intimacy affect your creative process?

FM: Anna and me share a studio since we moved to New York five years ago. In many ways our creative processes are intertwined, reflect and complement each other - like an infinite mirrored mental space, that we share life and work in. It is very beautiful, some times really intense but always very fruitful.

This situation became the ground for our recent collaboration, the project "Late Checkout", with Simone Subal for Liste Art Fair in Basel. We conceived the concept and worked on it together from the beginning to the end. For "Late Checkout" we did several paintings together: digital sketches, collected from my phone, and translated to bed-sheet like fabrics. We also created a series of new films, all shot in different luxury high-rise Hotels across NYC. Always confronted with the same setup: a small, isolated room in a new condo building, with one gigantic wall of windows. Trapped behind a 'screen', in a vacuum of a room, we manage to get almost enough space between us, to conduct a choreography of intimacy via the screen - as the camera that I control is wirelessly connected to the smartphone Anna is keeping. Broadcasted in a live-stream, she sees what I see, classical roles are overcome and we melt into voyeurs of ourselves – via the screens, ultimately connected but always apart, we become silent actors, enacting a muted script to the rhythm of the unimpeachable air-condition.

In the fall of 2016 we will have a collaborative show at Signal Gallery in Brooklyn, extending 'Late Checkout' into a full scale installative environment.

ALW: In one video called "You are certainly entitled to this opinion" you try to have a decent conversation with Apple's AI Siri, who fails to continue the dialogue. In contrast, the slow-motion video showing dogs licking their owner's face, demonstrates a succeeding relation and honest feelings between two creatures. Do you think the digital world threatens existential emotions and relations?

FM: There is something deeply disturbing and equally fascinating about the video "Furthermore, all the windows looked onto the courtyard and - from scarcely any distance - onto other windows of the same style, behind which could be glimpsed the stately outline of new windows opening onto a second courtyard". We all are these dogs and their owners. This extraordinary act of mutual self- affirmation is such a divine comedy of liking, sharing and following, subscribing, participating and aspiring. And while the tongues of the dogs become alien-like creatures, tenderly mapping the facial geography of their owners, the awareness drips homoeopathically into our consciousness, that it is not possible to actually ask Siri something essential. Within the digital sphere, I can’t help but feel the same sort of phantom pain that an amputated extremity would cause – whether it is watching a CGI animated character in a movie, listen to the voice of the robotic GPS device, or simply while surfing the WWW. It always feels like something is absent.

For me, this missing part is the human feature that I have previously mentioned. Something that provides a material, an inner necessity and cause; it is the symbiosis of substance and meaning, manifested in a physical body. An example of this is the discussion and, eventually, the refusal to digitally generate Philip Seymour Hoffman post mortem, in order to finish the missing parts of the movie "The Hunger Games". The symbiosis is symbolised by the wrinkles on Philip Seymour Hoffman's forehead, which were shaped throughout his entire life, caused by all experienced emotions and memories and their according facial expressions. A CGI software specialist simply wouldn’t be able to reanimate the actor in all his detail without insight and knowledge of his very nature, inner organisation and composition. This allegory can be stretched back to painting, as exactly those folds and wrinkles of paint are what I am trying to carve out on the canvas. Abstractly, I would ascribe all those missing human features of the digital sphere to the medium of painting, which specifically allows it to graduate into that of a human agent. And this is precisely, why the medium of painting is such a wonderful antagonist to the digital sphere for me.

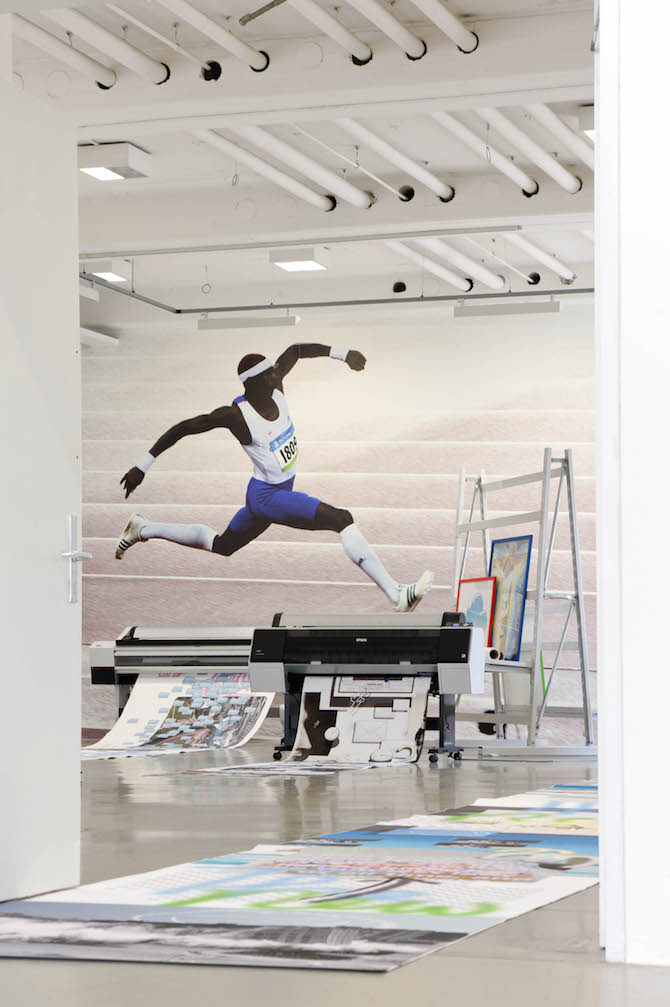

ALW: The use of online printers, receiving documents from friends, often adds a participatory aspect to your exhibitions. How do you envisage the role of the spectator?

FM: I am interested in revealing or creating structures and choreographies of collaboration around digital and analogue spheres. With its many-to-many concept of communication the Internet allows everyone to be an artist, actor and spectator, while simultaneously being a participant, a subscriber, a friend, a follower, and collaborator. Generally and philosophically there is equally as much upload as download. All roles naturally embrace the idea of a permanent flux. I would like the spectator to become those wrinkles on the forehead of the young Philip Seymour Hoffman: Defined and extravagant, but barely visible, I then might enjoy to redraw and emphasise the wrinkles with a black marker, after the spectator fell asleep after too many cocktails on the gallery couch, during the after opening party. Finally, I would probably take a lot of pictures of the spectator, alone and together with me and then post them on Instagram and maybe on Facebook.

FM: I am interested in revealing or creating structures and choreographies of collaboration around digital and analogue spheres. With its many-to-many concept of communication the Internet allows everyone to be an artist, actor and spectator, while simultaneously being a participant, a subscriber, a friend, a follower, and collaborator. Generally and philosophically there is equally as much upload as download. All roles naturally embrace the idea of a permanent flux. I would like the spectator to become those wrinkles on the forehead of the young Philip Seymour Hoffman: Defined and extravagant, but barely visible, I then might enjoy to redraw and emphasise the wrinkles with a black marker, after the spectator fell asleep after too many cocktails on the gallery couch, during the after opening party. Finally, I would probably take a lot of pictures of the spectator, alone and together with me and then post them on Instagram and maybe on Facebook.

For my show Somewhere sideways, down at an angle, but very close, last year at Wentrup Gallery, I created an environment resembling a virtual server room: It was full of floating images and data, comprising paintings that were installed on a wallpaper of the Photoshop transparency grid, videos on two huge flat screens and a network of cloud printers installed under the ceiling, for which I had asked friends, artist, curators, writers, musicians to send in postings from all over the world. It was a global live-feed choreography, printed in real-time, whenever the postings were sent. It was a concert, at times an intimate melody, and sometimes a cacophony of falling posts, all adding to the growing layers of paper on the floor. By exposing the postings to the physical world, they abandon the high-frequented realm of the Internet and its hyper-social apps, in order to be 'eternally' or tragically banned with ink on paper. They were exposed to corrosion and to the spectators. They stepped on them, left marks and traces on the papers or, in some cases, stole them or threw them away. They also introduced concepts of morality and censorship by turning posts with ‘inappropriate’ imagery face down. Thus, in many ways, the spectators graduated into a force of alteration for the show, questioning the contemporary qualities, limitations and conditions of being a user. All postings are already scanned and re-digitalised and will be printed out again, archived and published in a magazine format. There is also a tumblr that I am gradually feeding with images: somewheresideways.tumblr.com

ALW: Your paintings play with the aesthetic of stains; your videos are hardly processed. Are these strategies referring to a notion of authenticity, as opposed to perfection?

FM: The notions of authenticity and perfection are interesting in regard to the digital and analogue. Something that is too perfect is naturally suspect to us. In 3D modelling or CGI it is thus all about creating and integrating little imperfections or flaws to create the perfect illusion. Still, computers are not really good in simulating imperfection; they are much better in working perfect. Error remains a human domain.

FM: The notions of authenticity and perfection are interesting in regard to the digital and analogue. Something that is too perfect is naturally suspect to us. In 3D modelling or CGI it is thus all about creating and integrating little imperfections or flaws to create the perfect illusion. Still, computers are not really good in simulating imperfection; they are much better in working perfect. Error remains a human domain.

Since I started painting in 2004, I was mostly using unprimed canvas, in order to allow the organic components to merge: the oil paint, the oil and the canvas. In my paintings, the canvas warmly embraces the oil and the pigments, and it absorbs them to join into an almost eternal symbiosis. Here the oil stains are out of my reach, they bleed out as much their pretentiousness allows. They are one choice of imperfection, in a mostly pedantically controlled and preconceived process. Where I sometimes foresee every gesture and step a hundred times, not rarely over a timespan of months, until I might feel able to grasp the final choreography of my extremities, in order to leave the right traces at the right spot. The oil bleedings become stains of consciousness – a memory, indicating that something had happened here. Like blood on a carpet – maybe less direct, but definitely a transgression of a certain kind. The oil transgresses the canvas and makes it translucent - it changes the canvas' colour and the way that it deflects light, as light will simply shine through. I often emphasise this transgression by installing the paintings in the space rather than plain on the wall, referring to the space beyond and literally behind the canvas.

This is even more so, since I started to paint with pure linseed oil, depicting shapes, forms and objects without any pigment and started imprinting parts of my body onto the canvas, like my arms, my butt or my feet. Here, I am not referring to Yves Kline's attempt to revive the act of painting and expose its processuality by the use of ‘human brushes’, but rather to enact immaterial gestures within a medium embracing the material. Ghostly human traces, an afterglow of being – like the shroud of Turin is attempting to proof the existence of Christ, but instead it might just depict the grease of some Jesus, while simultaneously the grease is being swiped and pinched across the screens of our smartphones. These afterglows of human existence left on the screens of our devices, the digital screens of our phones, computers and of my canvases, emphasise the existence of one ultimate membrane, which I try to perforate.

ALW: What are you currently reading?

FM: Tolstoy: Selection of Short essays; Gia Edzgveradze: On some worn out notions; J.P. Sartre: Notebooks on a Phoney war, 1939-1940; J.P. Sartre: Nausea; My old emails from 2004; Antonin Artaud: Biography; Boris Groys: On the New; Netflix 1 star reviews

ALW: Some of your work's titles embrace entire cultural phenomena, such as "Guernica, mon amour, give all and get something (Postmodern Trauma)" or "Post Modernistic Traumas In Glittering Colors". How would you describe a Postmodern Trauma?

FM: One symptom of our age is the jet leg of meaning in the Internet: As information is rapidly shared with a focus on visual appearance, instantaneously, the meaning and inner necessity appears to be left behind – jet lagged, so to speak. There is an incredible short half-life, data falls apart and becomes uninteresting in the very same moment, as it is created. It seems that there is simply no time, and there might be no need for the inner necessity of things or phenomena.

FM: One symptom of our age is the jet leg of meaning in the Internet: As information is rapidly shared with a focus on visual appearance, instantaneously, the meaning and inner necessity appears to be left behind – jet lagged, so to speak. There is an incredible short half-life, data falls apart and becomes uninteresting in the very same moment, as it is created. It seems that there is simply no time, and there might be no need for the inner necessity of things or phenomena.

This leads to another contemporary condition – the state of hyper-synchronised-mimesis: For my show Delivery to the following recipients failed permanently at Simone Subal in NYC I developed a real-time-interactive-fluid-simulation together with Harvest Works NY. There were two screens, occupying the main axis of the show with each Plexiglas screen on either end of the gallery, depicting a dark animated liquid that floats in front of self designed skyboxes, back-dropping historic scenes in a zero-gravity atmosphere.

We connected the program with several 3D free sharing databases, for example from Universities or the NASA. Both liquids actively searched those databases for random 3D models, to integrate them via a live- feed into their stages, and to eventually absorb them after a short dance. We programmed the liquids for them to would register each other’s activity, thus influencing each other's choices. If one liquid was downloading a 3D model, of, say, a red car, there was an increased chance that the other liquid would search for something in the same category of a similar shape, fashion, colour or size. This caused a permanent hyper-synchronised-mimesis of up and download between the two, reflecting our contemporary user condition, which is and will be endlessly fed by the infinite and constantly updated digital ready-mades of the Internet.

ALW: You recently had a show at Kasseler Kunstverein called "The New World Hotel". Is this hotel in the future, or already in the now?

FM: The New World Hotel actually exist: in China Town, NY as the Hotel receiving by far the worst reviews by customers of all NYC hotels. But it was also the emulation of another version - this bed bug infested reality - post apocalyptic, but highly utopian.

FM: The New World Hotel actually exist: in China Town, NY as the Hotel receiving by far the worst reviews by customers of all NYC hotels. But it was also the emulation of another version - this bed bug infested reality - post apocalyptic, but highly utopian.

ALW: How do you feel about the future?

FM: Oh, can I download it for free?

Florian Meisenberg on vimeo: vimeo.com/florianmeisenberg

and on YouTube: youtube.com/user/floopister

UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS

FLORIAN MEISENBERG

Why we expect more from technology and less from each other, (Verena Dengler, Florian Meisenberg, David Renggli, Gabriele de Santis), Wentrup, Berlin, Germany, Opening 10 September 2015, Exhibition 11 September – 21 October 2015

Save the Data! Kunstpalais Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany, Opening 26 September 2015,

Exhibition 27 September – 15 November 2015, curated by Amely Deiss

Casual Gestures (with Claudia Djabbari, Bruce McLean, Gregoire Motte, Luke McCreadie, Philip Ewe and Laurence Payot), Standpoint Gallery, London, Great Britain, 07 November – 06 December 2015, curated by Flore Nove-Josserand & Thorbjorn Andersen

curated by Martina Weinhart

Solo show at Murias Centeno, Lisbon, Portugal, 2016

Anna K.E. & Florian Meisenberg at Signal, Brooklyn, NY

ANNA K.E.

Teen Factory (Berlin - NY), Barbara Thumm, Berlin, Opening 10th of September, Simone Subal, NY, Opening 12th of Septmeber

all images: works by Florian Meisenberg, © Florian Meisenberg, courtesy the artist, Kassler Kunstverein and his galleries Wentrup, Berlin; Simone Subal, NYC; Mendes Wood, Sau Paulo; photos by Joerg Lohse, NY; Sebastian Bach, NY; Anna Arca, London; Trevor Good, Berlin; Nils Klinger, Kassel; Bruno Leão, São Paulo; Gui Gomes, São Paulo