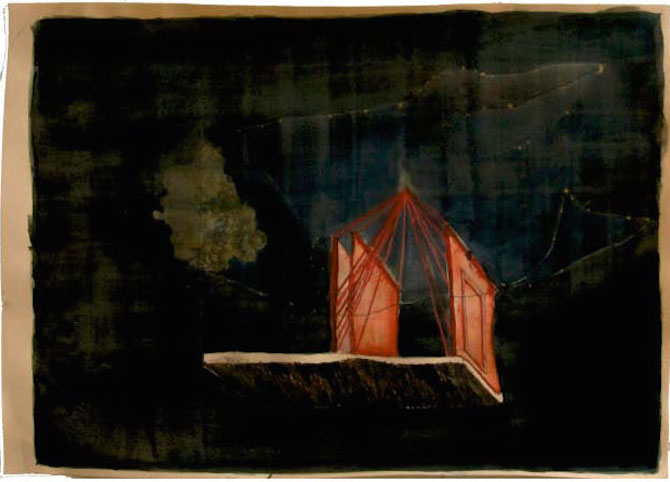

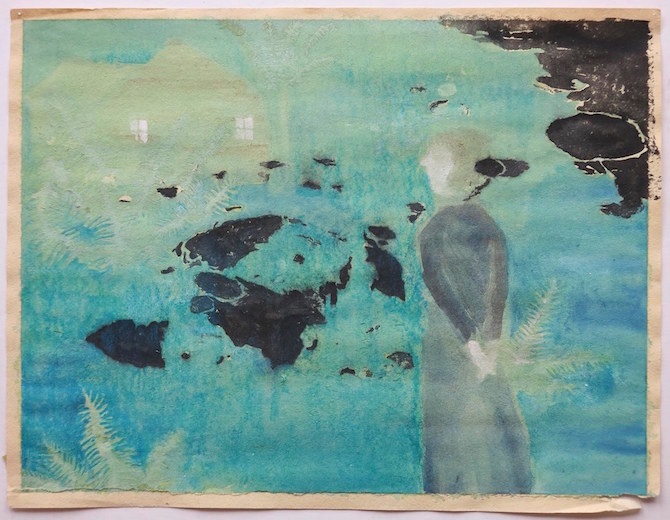

work by Anders Dickson, courtesy the artist

Anders Dickson is a 1988 American-born artist who has been based in Germany for the past five years. Having previously studied Philosophy in The States, he is now a student of Monika Baer and Amy Silman at The Städelschule Frankfurt. While Dickson works in several mediums, his dreamlike subjects and unique use of colour make his pieces pervade a sense of the supernal. Inspired by elements of American culture; from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, to the Native American figure of the ‘Trickster’, the artist balances elements of mythology, philosophy and nature in order to confront the mystery of human identity in contemporary society. Dickson’s work is currently on view as part of a group show ‘Der zweite Blick’ at Galerie Scharmann & Laskowski in Cologne.

Frederica Miller: You work in various mediums. Is there a particular one in which you feel most at home?

Anders Dickson: Drawing. It was my drawings that lead me both to painting, sculpture and installation. Drawing goes hand in hand with thought, and because of that I feel far more at home and closer to my thoughts within the realm of drawing.

Frederica: Your work contains symbolic and spiritual elements that bring to mind the theories of Carl Jung. As a former philosophy student, what was it that made you switch to art?

Anders Dickson: I studied philosophy for three years, but I had also been drawing and painting since I was a kid. Throughout my time at the universities in Duluth and Minneapolis questions were constantly posed and few answers were provided. There's also a tendency amongst philosophers to make their biographies the guidelines upon which they build up their philosophies. I felt eventually that I ought to follow that which brings me into moments of time, loss and enjoyment and furthermore that led me to try and create my own path.

Frederica: You have previously mentioned Rupert Sheldrake’s controversial parapsychological theory of ‘Morphic Resonance’ in relation to your work. Do you believe in his notion of ‘collective instinctive memory’?

Anders: I totally believe in collective instinctive memory. To feel that every object has it's own stored collective memory falls in line with my own insights to the nature of my reality and as far as it goes with my artistic practice I think that it is conducive to a process of "novice-alchemical" interactions. I believe that the materials I use are already imbedded with a certain history and story. Like humans, they have developed over time and this history is stored amongst not the individual but amongst the whole of them.

Frederica: You list Herman Melville’s ‘Moby Dick’ amongst your influences. What is it about this book that particularly inspires you?

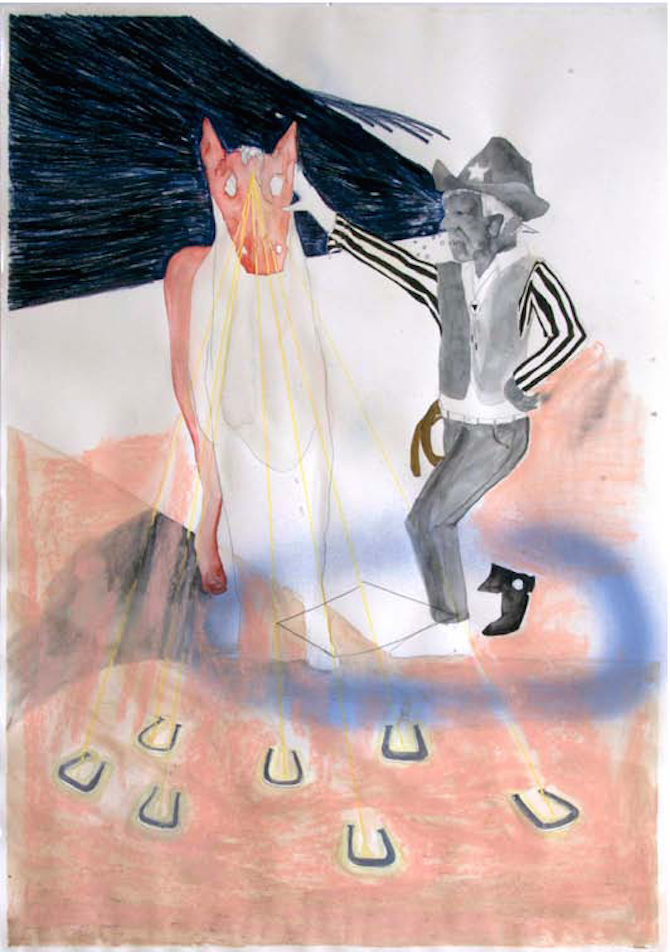

Anders: Moby Dick is amazing. There are so many beautiful moments where Melville’s writing seems to be contemporaneous with the stream of consciousness style that I love in writers like Kerouac; particularly the moment when Pip, the cabin boy, experiences an almost psychedelic communion with god when he is left drifting in the waters after falling out of the boat during a whale chase. I also love Moby Dick in light of Deleuzes's idea of "becoming": Captain Ahab loses his leg to a whale, afterwards he takes a whales' bone as a peg-leg. Ahab also begins to exhibit characteristics of whales: he adapts the migratory path of the whales, he rarely comes to the surface to interact with his crew and he spends most of his time in the dark. Moby Dick is referred to as if he was human and becomes Ahab’s obsession. This morphing of human to animal, animal to human is really interesting to me.

Frederica: Some of your work deals with contemporary American culture. In particular ‘O.T’ – a watercolour painting that depicts a young boy cradling a gun while his torso-less, mother stands over him. Do you see art as an effective tool for political change?

Anders: Sure, art can be used as an effective tool and catalyst for change. I guess it ultimately depends a lot more on the intention of the artist though, whether it is actually a political tool or not. Works can be picked up by people and used to support their agenda but then it empties the work of it's original value, it kind of rapes it of it's own autonomy and vibration. I don't intend to engage with the political discourse in my works, but, yeah, in the particular watercolour you're referring to it can be read as extremely American. We're all obsessed with guns. I don't pay attention so much to the politics shown in the media, but I think I have my own maybe made-up ideas of political figures in relation to this world I’m inventing for myself.

Frederica: How intrinsic is your American nationality to your work?

Anders: The fact that I’m American plays a large role in my work. Many of my themes are based and rooted in American culture and history: the ‘Trickster’ figure of the Native Americans, Basketball or Hippy-nature. This is something I've more recently started thinking about how to locate myself in the art context. It's strange, because I don't feel like an American artist. Since living in Germany now for more than five years I have attended art schools and I’ve been raised in the context of German art. This for me throws light unto the strange nature of the artist operating as a vampire or jester or trickster in society. My nationality inevitably pokes through the works in moments, but it's not my focus to make American art.

Frederica: You just mentioned the figure of the ‘Trickster’; ‘a mischievous spirit or anthropomorphic animal who possesses secret knowledge, plays tricks and disobeys conventional behaviour’. How do you, as an artist, identify yourself as a ‘Trickster’?

Anders: I think the artist has a very interesting role in society and as far as I understand the Trickster, I can notice and draw many parallels between the two. The Trickster acts first and asks questions later; as portrayed in a lot of Native American mythologies, it's the tricksters to whom credit is given for the discovery of truths, and the establishment of certain codes. He is responsible for first realising that tobacco can be smoked, that the bear gives his meat to humans for food, and even for something as strange as for the current length of the human penis. He operates on his own intention; he's not inside of society but in front of it, and I think that as artists we are allowed also to step outside of society and discover our own rules, truths, logic and morals. I’m fine with acting and later realising I'm an idiot or fool, but through that I learn something

Frederica: Many of your works feature animals or are set in rural surroundings; what is it about the natural world that interests you?

Anders: That has a lot to do with how I grew up: I was raised in the woods of the Midwest. In Minnesota and Wisconsin our family moved around and we always were living in the forest somehow, and naturally as a part of that I was just constantly in contact with animals either by way of going along on hunting trips, walking around, camping…. I am also influenced by things like Disney movies and cartoons, since I grew up watching all these strange children's show's in which animals are the main characters. This also pairs up with a fascination in Native American Culture and Mythology; the animals are brothers and are personified like humans.

Frederica: Why so many cats?

Anders: Last year at some point I began drawing pictures of cats, more or less unconsciously. As time went on it became more like an obsession and I couldn't stop, eventually I felt myself trying to avoid cats as a subject matter and as that came I made a work to end this obsession. It was an aluminium cast of cat heads piled up on top of each other like a totem pole. Then I thought it was over, my cat obsession was through, but alas, the cat popped back into the works again. I think I adore it as an image affiliated with superstition, paranormal and the night. I'm more a dog fan than a cat fan, but as far as it is a symbol I like to implement it in my work as a loaded hint towards the paranormal.

Frederica: You are not afraid to mix mediums and often combine several motives in one piece; do you work instinctively or do you have a clear plan of the piece that you want to create before you begin?

Anders: This is something I've sought to find a proper middle ground between, because I feel like both styles of working have their merit. In the past year I’ve began working way more instinctively. It's fascinating to set out on a path and be constantly responsive to the material and spontaneity of the works. In many cases I’ll have a vague idea of what I want to make, either as a sculpture or drawing, and with that image in mind I'll set out to execute it. I don't often make sketches or plans for the works, but allow them to be their own. The engagement with an object or image is not a one-way relationship, rather it's more of a conversation: the work is screaming at you to finish it. This is what I mean by being responsive to the work, we are constantly talking with our pieces.

Frederica: The conversations that you have with your pieces often seem to be playful. Do you think that it’s important for art to have a sense of humour?

Anders: Recently I saw a show in Berlin, which dealt with the topic of humour. Something that stuck in my mind from that show was the statement that humour has to do with self-reflectivity. As far as it is an issue of taste I think it's good when work has a sense of humour, although I don't know if it was actually the artists' intention that the work should be read as funny: For example, I think Donald Judd’s works are pretty humorous. I think my works are playful and I like that they read as playful and warm. I've been wondering more about cynicism lately and whether works ought to have a hint of the cynical in them?

Frederica: Do you think they need to be cynical, as that would prove their self-reflectivity?

Anders: I’ve been thinking about this, whether a work needs to somehow poke itself in the ribs in order to test it's own strength? This hard self-reflectiveness can be a way of closing and proving a work’s invulnerability. I think my own works are pretty open and receptive. They are warm and adding an aspect of cynicism to them would feel contrary to my own aims. While some artwork benefits from cynicism, I don't think it's necessary. Self-reflectiveness is important though, and it's interesting to be able to step away and watch yourself in the studio, and to see how the response formulated from the act of objectifying your practice can be either cynical or positive.

Current exhibition

Der zweite Blick

with Anders Dickson, Hervé Garcia und Vladimír Houdek

Scharmann-Laskowski

Schaafenstr. 10

50676 Cologne

Oening Hours: Wed-Fr 14-18h, Sat 12-16h

Current exhibition

Der zweite Blick

with Anders Dickson, Hervé Garcia und Vladimír Houdek

Scharmann-Laskowski

Schaafenstr. 10

50676 Cologne

Oening Hours: Wed-Fr 14-18h, Sat 12-16h

work by Anders Dickson, courtesy the artist // last image © photo credit: Tamara Lorenz.

work by Anders Dickson, courtesy the artist // last image © photo credit: Tamara Lorenz.