all images: works by Elizabeth Willing, at Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, © and courtesy Elizabeth Willing

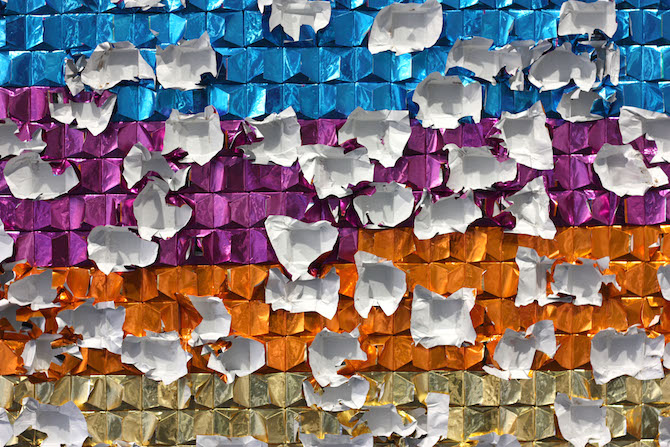

On a distance, the wall object looks like an abstract version of a David Hockney landscape painting. But closer inspection reveals: it is 3000 pieces of chocolate, the type of creamy and cold tasting German Eiskonfekt, wrapped in differently coloured shiny papers. This work, like many other pieces from Australian artist Elizabeth Willing, may be eaten by gallery visitors. Usually based in her hometown Brisbane, where she finished her fine art studies, 1988-born Elizabeth came to Germany and worked with Thomas Rentmeister

for a few months until she began her

one-year artist residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. Her sculptural work is mostly made of food or it is related to food products, eating and cooking habits. While usually ephemeral, the objects perform their own fleeting process either through their consumption or through their evident, limited sustainability. Strong smells of food, such as cheese, are paired with materials, interfering the perception of other pieces through multi-sensory manipulation and thus sabotaging the common anticipation. Elizabeth stages food as as solid material, but, always with a wink, she also wittily reveals our complicate relationship to the moral politics and the ethics of food.

Anna-Lena Werner: Elizabeth, what did you have for dinner last night?

Elizabeth Willing: An orange, tomato and cheese on bread. The orange was not on the bread. It was radically boring.

Anna-Lena: Most of your sculptures are made of food. Why is it so interesting to you?

Elizabeth: When I first began using food I was fascinated by baking, specifically how scientific it was. I liked that you could whip, knead, cream, and rub fats and sugars together in so many ways and each gave a different result. Now though, I would say my and other people’s anxieties around food and eating are a major drive for my work. Eating right, eating ethically, is such a big deal, and it causes so much anxiety for me and other people I can see. I think about food and my own decisions quite a lot. We have various problems with food in my family. I love watching food fads come in and out, seeing what amazing development occur in molecular gastronomy, how extremely pretentious people can get with their food choices.

Anna-Lena: You just spent one year in Berlin at the residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien. What did you learn about German food?

Elizabeth: I was a little underwhelmed. I used a lot of Turkish food, because I am in a very Turkish area here in Kreuzberg. It is exciting how open the German food industry is to outside influence and experimentation, it results in interesting new concept restaurants and creative food projects. I like the ‘small fridge’ thing you guys have going, because in Australia we only have small fridges in dorm rooms at university. The small fridge and small freezer is a positive thing, because food should be eaten fresh for maximum taste. I am truly shocked to find this jelly aspic stuff rampant throughout the cold meat section. And, although my citizenship will be revoked for saying this, I think the Germans really know how to BBQ. They are on par if not better then the Aussies and it helps that they find a way of doing it almost anywhere.

Anna-Lena: What quality in food elevates it to be a useful artistic material?

Elizabeth: I think a quality that is really good to have is the right shelf-life. A kind of food that will retain all its qualities for at least the three weeks of an exhibition – that way all the viewers are getting the same experience of the work. If the work is interactive or edible, I want it to be safe to eat three weeks into the show. I am not so interested in revisiting the idea of revulsion or vanitas, which inevitably comes up when using fresh products. A material either needs to perform in some way, or it allows me to tell a story through my interaction with the material.

Anna-Lena: How do you test a new material?

Elizabeth: I bring it to the studio and try a whole bunch of things out with it: making it stick to itself in various ways, building with it, squashing it, using it as a stamp, essentially pushing the structural limitations of it. But I also try possibilities for it to have a dialogue with my body, or with the act of consumption.

Anna-Lena: The act of consumption was a big part of the wall object “Afternoon pick-me-up” that you just exhibited at Künstlerhaus Bethanien. It looked like a landscape painting, but actually consisted of more than 3000 wrapped chocolate pieces that visitors were allowed to eat. Is it easy for you to transfer the responsibility of the work to strangers?

Elizabeth: When planning the work I make guesses about how the work will be interacted with, and in those planning stages I have a false sense of control. So when I do hand over the responsibility to the audience I panic, because inevitably people make up their own rules. I am trying to get better at predicting peoples movements, or at least to relax about the resulting chaos. In other words, no its not easy, but I keep doing it because I enjoy making these huge interactive pieces.

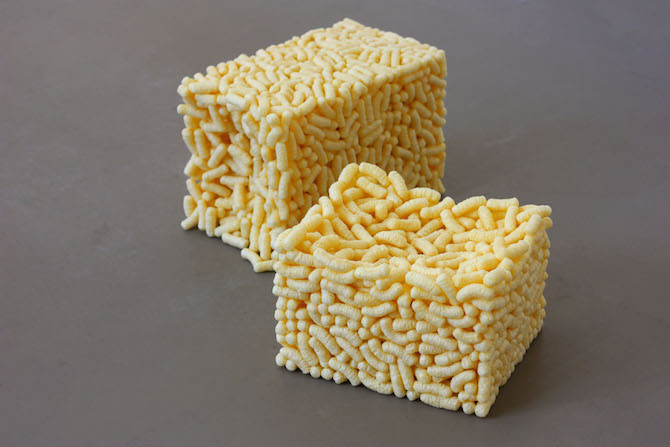

Anna-Lena: The show’s title “Shades of Yellow” referred to cheese that you used. Do you keep these works after dismounting the show, even when they stink?

Elizabeth: The ones I like I did, but lots go in the bin. The older ones are actually more bearable, they have already leeched all their fats and so they are mostly smell free after a few months. Its the new ones that are the worst to deal with.

Anna-Lena: You said that you have a show coming up in a commercial gallery in your home town Brisbane this year. How can you sell your work, if it begins to rot or stink within a couple of weeks?

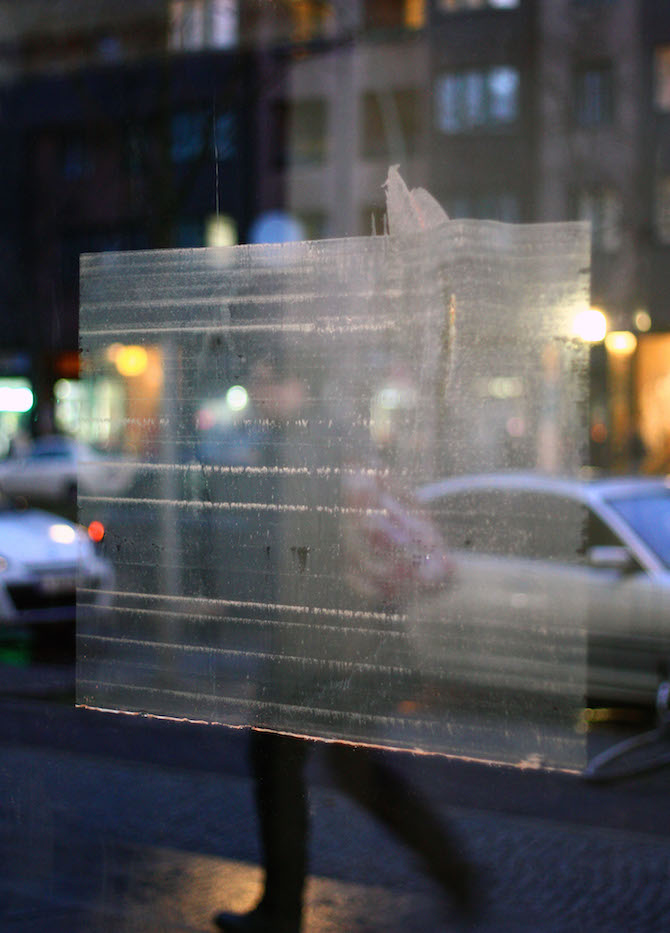

Elizabeth: I can’t sell that stuff. At least not to the kind of collectors that Australia has. They are more conservative. The show will be made up of collage, drawings, and printmaking. There will also be a few ephemeral and performance pieces to contextualise the rest of the work. I love stinking up the gallery with artworks. It makes it multi sensory, especially when it bleeds over to other artworks, like the cheese smell with the meat-plate collage at Künstlerhaus Bethanien.

Anna-Lena: The smell is really invasive. I think it manipulates the choreography of walking through your works.

Elizabeth: Sometimes it is an accident that occurs during install, very rarely I have a concrete idea of what and where things will go in an exhibition space. Pairings of works and smells just get stuck and complicate each other, or distract from each other. Also, since I often manipulate the material beyond recognition, I like to have the smell to give hints to what the material is. The cheese for example is quite an ambiguous material, but perhaps the smell can give clues.

Anna-Lena: How is the cheese ambiguous?

Elizabeth: On first inspection many people think it is some kind of plastic. It has a hard glazed look when its dry. When its fresh, it is like a fine clay — it has the ability to be joined very easily. I am at this point not interested in using it outside its readymade form of a square though. The cheese needs to keep its processed shape.

Anna-Lena: Movements related to food have a strong focus in your work.

Elizabeth: The act of cooking and eating has a beautiful choreography to it. I used to focus on my body, when I would do something monotonous like packing strawberries at an old job I used to have on a farm. The body repeats actions in such a mechanical way. I like the phrase of ‘muscle memory’.

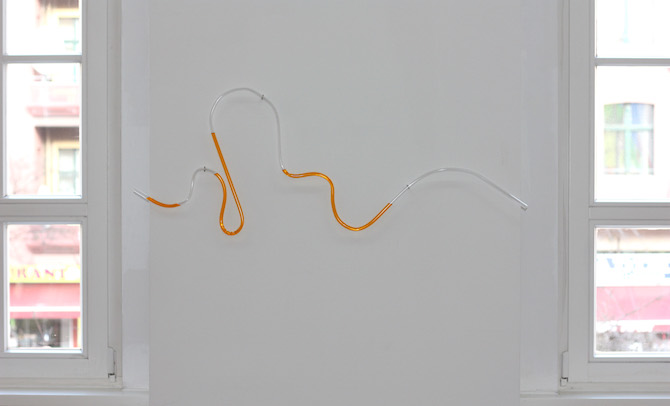

Anna-Lena: Your sculpture “Measure, pinch, roll, check, knead” shows five suspended, cut-out hands that you initially found in cookbooks. Is this work also related to movements?

Elizabeth: I have been thinking about the hand as our most sophisticated tool for cooking, the way it retains the complex actions of cooking and eating and repeat them daily. Our hands have all these abilities that go beyond language, and that is what art like dance does: to communicate without language. I like the moment when you try to explain the process in a recipe and words fail you, when we say words like ‘a bit’ ‘a pinch’ or ‘roll’ – these need to be seen and repeated to be understood. And then we have the knowledge in our hands. That is where the work comes from. I tried to emphasise the movement and rhythm of a recipe through the spinning hands, allow them to overlap with each other and create new combinations of movements. It comes back to learning from our parents, our mothers mostly, and to how much can we really learn from a still image in a cookbook.

Anna-Lena: Your next stop is a short residency in Helsinki. What will you be doing there?

Elizabeth: I am going to Helsinki to look into foraging culture, which I am fascinated by. I am extremely curious about this for two reasons, firstly it is something we do not do in Australia, and secondly it is becoming very fashionable in Haute Cuisine. A return to local, foraged food is the philosophy of a handful of the top restaurants in the world. I am curious about the cycle of western food culture, the way it uses all the technology and recourses at its disposal to deliver all varieties of food all year round, a luxury goods market, and then the scale tips and fashionable people take a back-to-basics approach of living off the land.

all images: works by Elizabeth Willing, at Künstlerhaus Bethanien Berlin, © and courtesy Elizabeth Willing