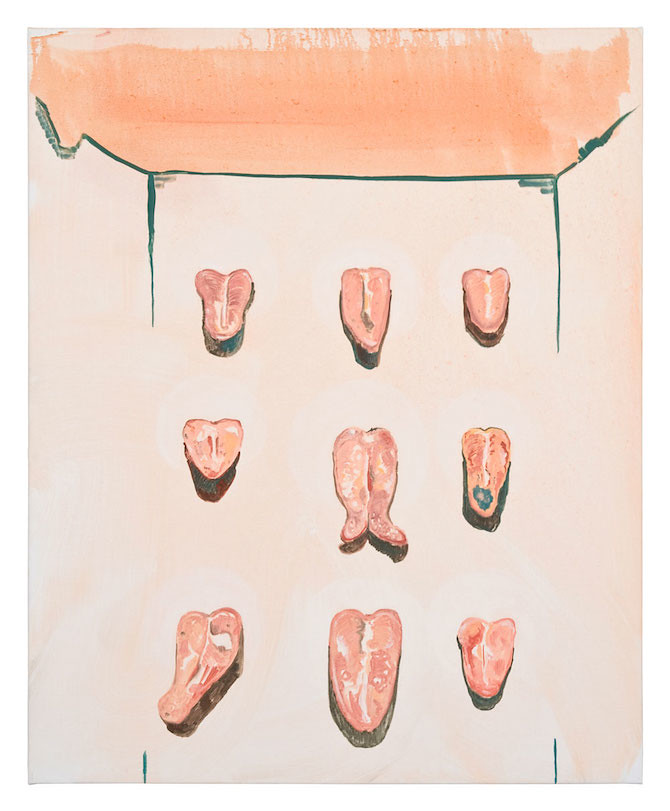

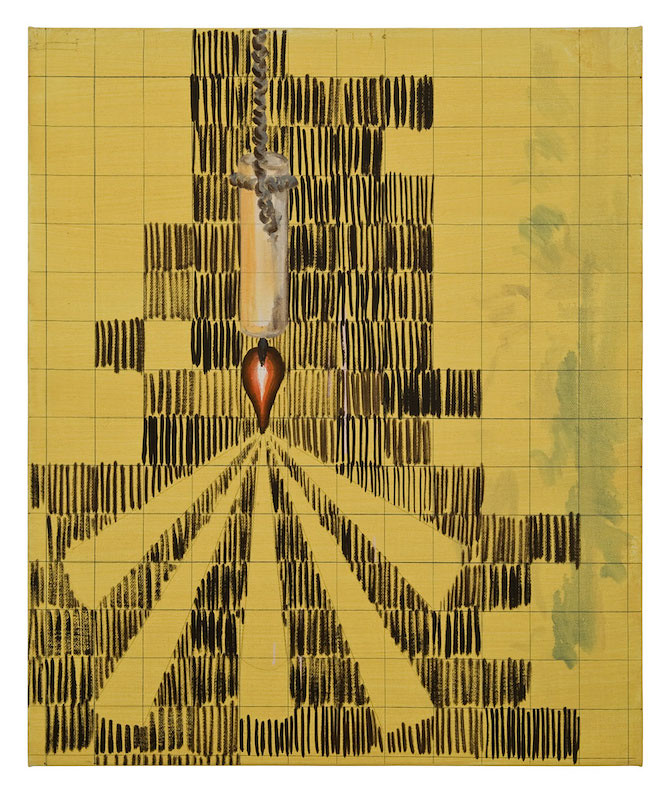

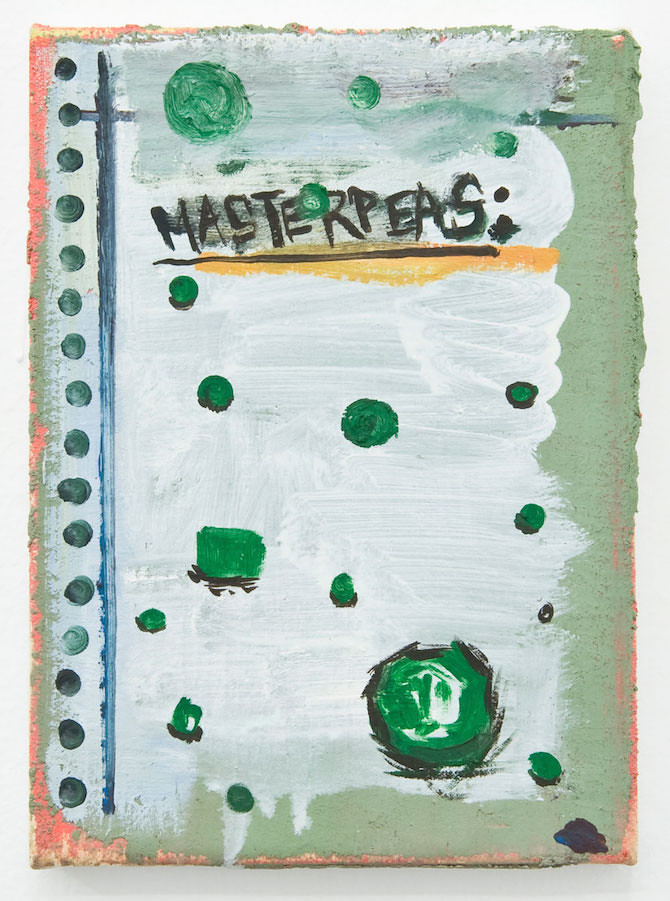

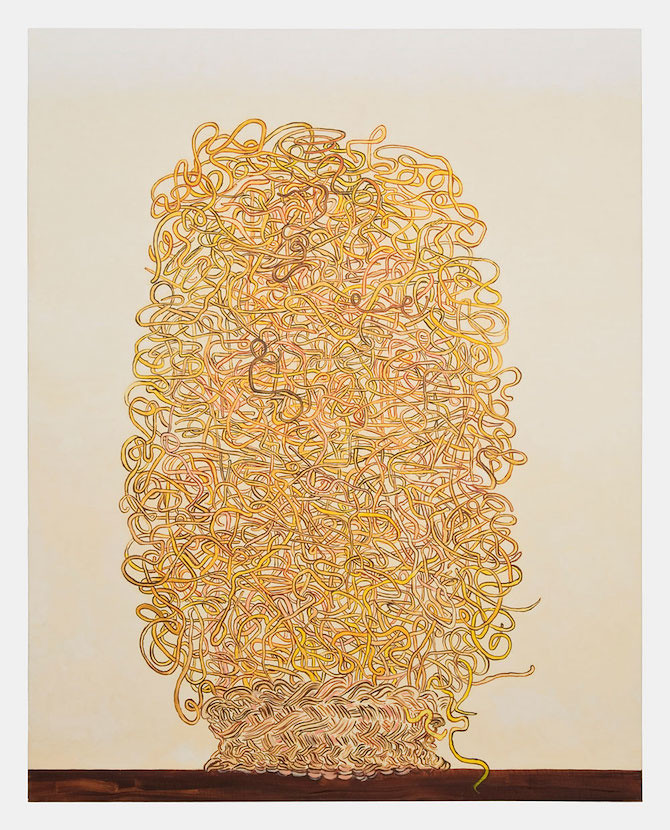

all works by Rasmus Nilausen at Traneudstillingen, Copenhagen, courtesy and © Rasmus Nilausen

all works by Rasmus Nilausen at Traneudstillingen, Copenhagen, courtesy and © Rasmus Nilausen

There is something boy'ish about the way Rasmus Nilausen smiles. Its like a small blink. As if he knew a funny thing that he decided not to share. And it is a very similar misteriousness that can be found in his paintings: each holding a story that is suggested through symbolic references, the paintings' visual appearance often guides in a completely different direction. Sometimes funny, sometimes tragic and sometimes just absurd. Based in Barcelona for more than a decade, the a 35-year old Danish painter uses his exhibitions to reformulate and, specifically, to re-invent the way we look at paintings. He tracks down the process of painting – unfolds it to its very basic techniques – and finds a new literalness to tell their stories. Rasmus explores the recipe of historical masterpieces and proceeds hoping that, as he has stated in a previous interview in 2011, "the perfect painting is always the one that I am about to paint – the next one." Having shown his works in art institutions, such as the ICA in London and Fundació Tàpies in Barcelona, Salvatore, his current exhibition at Traneudstillingen in Copenhagen is his first show in Denmark.

Anna-Lena: Rasmus, many of your paintings are closely linked to a specific story. Could you have been a writer, too?

Rasmus:

When I was younger I was keen on becoming a writer, but I am not sure if I would be able to deal with this constant possibility of editing, which is an essential part of writing. There are only so-many layers a painting can physically hold. You reach a point where it becomes redundant and impossible to re-work it. I really like that, because it either forces me to start over or to abandon the idea completely. In my paintings there are stories, but they are not necessarily visible for the viewer. There is this unarticulated potential waiting to be discovered.

Anna-Lena: Salvatore refers to a character from an Umberto Eco novel, while the exhibition space is located inside a Danish library. How much do books influence your practice?

Anna-Lena: Salvatore refers to a character from an Umberto Eco novel, while the exhibition space is located inside a Danish library. How much do books influence your practice?

Rasmus: The novel The Name of the Rose takes place in a fictional monastery. The books and the library are key elements to the plot – that is why I thought of ‘Salvatore’ to be such a good fit in the first place. Obviously, books are important to me and I get many ideas from reading. But it doesn’t necessarily have to be an entire text – it can be just a short phrase that seems ambiguous, allowing me to elaborate. Actually, I am not quite sure how one gets ideas. Rather than theoretical texts, images or conversations, links and misunderstandings in language can trigger really good works.

Anna-Lena: Is there a recent misunderstanding that comes to your mind?

Anna-Lena: Is there a recent misunderstanding that comes to your mind?

Rasmus: It is like this game I play, where I pretend to hear something that sounds like something else and then rephrase it as a question. I just finished a work called Nature Morte, which is the French translation of Still Life. Basically it is just a picture of a tomb with the word Nature written over it.

Anna-Lena: Can you tell me about your work Museum of Tongues? What is it about?

Anna-Lena: Can you tell me about your work Museum of Tongues? What is it about?

Rasmus:

I find the idea of language as imagery fascinating. Language can also be understood as tongues – hence the saying, to be speaking in tongues. I enjoy translating spoken language in a literal way. Just in front of my old studio in Barcelona, there were these huge abandoned old factory buildings, which the city had planned to turn into what they called “The Museum of Tongues”. The project was never realised, because of the economical recession. Also it made me think of my own day-to-day, where I speak Danish with my daughter, Catalan with her mother, read most things in English and also tend to speak Spanish quite a lot. Somehow it is complicated to remain the same person across several languages. Like when Salvatore speaks all languages and at the same time none.

Anna-Lena: Light – often as a candle or a light bulb – is a reappearing motif in your work. Does it function like an allegory for the practice of painting, referring to basic light and shadow techniques?

Anna-Lena: Light – often as a candle or a light bulb – is a reappearing motif in your work. Does it function like an allegory for the practice of painting, referring to basic light and shadow techniques?

Rasmus: Yes. It is quite banal, actually. This has something to do with what I call the Technology of Painting. Summed-up by three very basic elements: Light, object and shadow. Combined, they are all you need in order to create the illusion of what we call painterly space. The candle halfway burned down is the allegory of our lifetime in Baroque painting. But in 20th Century interior paintings by, let’s say Francis Bacon or Philip Guston, the lonely light bulb is often the only visible source of illumination in a work.

Anna-Lena: You installed the painting The Light Bulb very high, on the wall of the library’s interior balcony. There is an awkwardness about this placing, although the motif – again, referring to illumination – makes a lot of sense there. Do you often integrate site-specific elements in your exhibitions?

Anna-Lena: You installed the painting The Light Bulb very high, on the wall of the library’s interior balcony. There is an awkwardness about this placing, although the motif – again, referring to illumination – makes a lot of sense there. Do you often integrate site-specific elements in your exhibitions?

Rasmus:

I do, because I have a lot of fun with that sort of thing. At times even too much fun. For Salvatore I painted one of the columns as if it was made of marble, just like the space’s flooring – creating a parallelism between the two. It is a very subtle, but also a clumsy installation. Quite easily overlooked, but once you see it, you realise how badly made it really is. I like it when painting reveals itself.

Anna-Lena: Another symbolism, also referring to the act of painting, is represented by green dots, which appear in a painting of yours that says "The Masterpeas" The so-called masterpiece has become something like a myth – do you believe that it could exist?

Anna-Lena: Another symbolism, also referring to the act of painting, is represented by green dots, which appear in a painting of yours that says "The Masterpeas" The so-called masterpiece has become something like a myth – do you believe that it could exist?

Rasmus: The dots, or circles are from a classical point of view the perfect shape. It is the shape of omnipotence. The peas reveal my feeling of the perfect work or the perfect painting, as something that can only exist as long as it remains unfinished. This is originally an idea formulated by Honoré de Balzac in his book The Unknown Masterpiece...

Anna-Lena: What is a myth to you?

Anna-Lena: What is a myth to you?

Rasmus: To me, a myth is a story. More importantly, it is about belief. It has something to do with how we perceive things that we hear or see. It is about trusting the messenger I suppose. The myth of Zeuxis and Parrhasius, the myth of the origin of painting and Trompe l’oeil as a consequence are some of my favourite tales.

this interview initially appeared in a longer version on kopenhagen.dk

Salvatore

From 13.12.2014 to 08.02.2015

Gentofte Hovedbibliotek

Ahlmanns Allé 6

2900 Hellerup, Denmark

Opening Hours: Mon - Fri 10-8h, Sat 11-4h, Sun 11-4h

Form is What Happens (group)

10.01 - 28.02.2015

Spinnerei archiv massiv

Spinnereistraße 7, Haus 20 A

04179 Leipzig, Germany

Ahlmanns Allé 6

2900 Hellerup, Denmark

Opening Hours: Mon - Fri 10-8h, Sat 11-4h, Sun 11-4h

Form is What Happens (group)

10.01 - 28.02.2015

Spinnerei archiv massiv

Spinnereistraße 7, Haus 20 A

04179 Leipzig, Germany

Opening Hours: Tue–Sat 11—18h

all works by Rasmus Nilausen at Traneudstillingen, Copenhagen, courtesy and © Rasmus Nilausen

all works by Rasmus Nilausen at Traneudstillingen, Copenhagen, courtesy and © Rasmus Nilausen