It’s Monday the 14th of March - one day before the big opening of "Oppenheimer's Garden' at Thomas William's Gallery at Old Bond Street in London. We are walking up the stairs to the first floor where Norwegian artist and playwright Lars Elling gives us a warm welcome and introduces us to the new gallery space and his amazing, large-scale paintings. It’s his first solo-show in London. Before we start recording, Lars checks his mobile phone – his second child could be born any minute. He seems remarkably balanced and open-minded; mentions American collectors, Moby Dick and Velazquez. He is an incredibly well read and pensive family guy, who loves secrets, jazz and books – and who tries to avoid clichés by all means, yet they keep on hunting him. You will find more photos and the interview by clicking on the headline, or one of the photos below.

Anna-Lena Werner: Are you both, a painter and a playwright?

Lars Elling: I am basically a painter, but I do other little things by the side. Sometimes I have ideas that I cannot use in a painting and that’s when I write something instead. I usually work with another writer. He is more professional than me. And sometimes we manage to get produced.

AW: Can you tell me a bit about the time when you decided to become an artist?

LE: It’s a very clichéd- story: I was the little asthmatic kid, who spends too much time inside the house. I started painting around the age of five, but never really realised that painting is a job until I went to the academy. We have this National Military Service in Norway. I spend 15 months in the air force and that was by far the most stupid experience I have ever had in my life. Just realizing the incredible mediocrity of life and of people. I didn’t occur to me before. So that’s when I decided to be a painter. It seemed like the easy way out – I just continued what I always did.

AW: Do you still remember your first exhibition?

LE: I made series of apes from the zoo in Copenhagen – that was my first show. I didn’t sell anything and it was not a good gallery, but it got one really good review by one of the ‘good’ critics. That encouraged me.

AW: How important is the audience’s reaction to you?

LE: I spend 300 days a year by myself – making this – and when I finally decide to show it to someone it means a lot to me. I think everyone who denies the audiences importance is a liar or a very contrary person. Its not important while I work, but once the paintings are up on the wall it is. And I would never chance it anymore.

Lars Elling: I am basically a painter, but I do other little things by the side. Sometimes I have ideas that I cannot use in a painting and that’s when I write something instead. I usually work with another writer. He is more professional than me. And sometimes we manage to get produced.

AW: Can you tell me a bit about the time when you decided to become an artist?

LE: It’s a very clichéd- story: I was the little asthmatic kid, who spends too much time inside the house. I started painting around the age of five, but never really realised that painting is a job until I went to the academy. We have this National Military Service in Norway. I spend 15 months in the air force and that was by far the most stupid experience I have ever had in my life. Just realizing the incredible mediocrity of life and of people. I didn’t occur to me before. So that’s when I decided to be a painter. It seemed like the easy way out – I just continued what I always did.

AW: Do you still remember your first exhibition?

LE: I made series of apes from the zoo in Copenhagen – that was my first show. I didn’t sell anything and it was not a good gallery, but it got one really good review by one of the ‘good’ critics. That encouraged me.

AW: How important is the audience’s reaction to you?

LE: I spend 300 days a year by myself – making this – and when I finally decide to show it to someone it means a lot to me. I think everyone who denies the audiences importance is a liar or a very contrary person. Its not important while I work, but once the paintings are up on the wall it is. And I would never chance it anymore.

AW: Is the audience’s reaction very different when you compare Oslo and New York?

LE: Very different! The American’s are very factual and direct. Very experienced collectors with massive collections of de Kooning’s and Basquiat’s say things like “So? How do you do this?” They touch the paintings and just walk into it– it’s brilliant. I like that. They are very self-confident and they give you very unsophisticated, factual questions.

AW: And in Oslo?

LE: Well, first of all I know people in Oslo. It’s a small city. There are good artworks and many artists who are very intelligent, but there is a lack of self-confidence. Any debate can be killed if someone says: “This debate is so pretentious – this would never happen in Berlin, or in New York.” No one disagrees; everyone is fairly respectful of the outside world.

AW: What’s your favourite place in Oslo?

LE: My log cabin in the woods. It’s just outside the city-centre. I often take my family and friends there. We don’t have electricity there and we get water from the stream. It’s really in the middle of the woods-

AW: Did you ever consider moving to New York?

LE: I have been there quite a lot, but my family situation prevents it. I am very stationary and obsessed with my studio space. It’s quite large and it’s always the same unless I change it. If I could transport that space somewhere else I could work anywhere. I hate that feeling of having to change everything – that would take years from my life. I do like to travel, but I like the working surroundings to be predictable, because the work in itself has no predictability.

AW: When you start a painting you don’t know how the outcome will be?

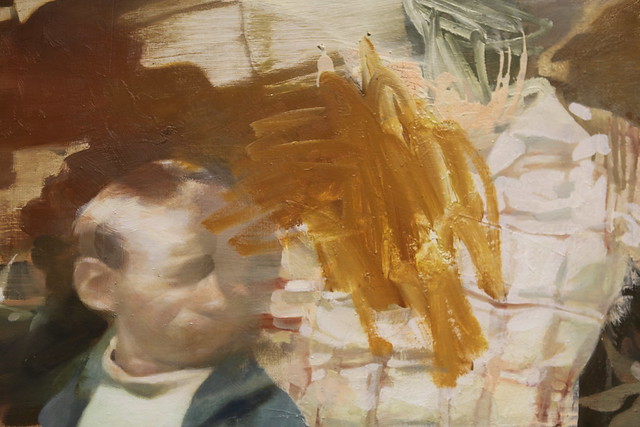

LE: I don’t sketch. Every painting contains layers of other figures that disappear. The composition changes gradually. If I manage to keep the painting alive for a long time then eventually it will turn into something interesting.

AW: Do you ever show unfinished works to your friends, or family?

LE: I do, sometimes. I have a couple of painter-friends, who work in styles very different from my own. But I only show unfinished works to people who like my projects and like me. In these moments I need a lot of support and little criticism, not the other way around. It’s a fragile process –why would you challenge that? It is difficult enough as it is. I don’t punish myself by asking people who hate painting.

AW: How would you describe a normal working day in your life in Oslo?

LE: I am a family man, with one child and another one in the making. It is fairly regular. I rarely work nights anymore. These long stretches were you work beyond exhaustion – when the whole painting is wet and in movement – that’s when interesting stuff and big changes can happen. I am always searching for what doesn’t look like a cliché to me, like a little invention that I can enjoy.

AW: Do you hate clichés that much?

LE: I do. Though, my subject matters are sometimes born on clichés. They can be interesting as well. There is a language there, but when it becomes repeated and banal then its not interesting anymore. You have to show them in a different way and give clichés a twist.

AW: Do you read while you are in phases of painting?

LE: I have always read an incredible amount – around 50 to 60 volumes a year.

AW: What music do you listen to while painting?

LE: I mainly listen to jazz.

AW: Does that influence your work?

LE: Very much. For my previous show I listened to Maiden Voyage by Herbie Hancock, Love Supreme by John Coltrane and In a Silent Way by Miles Davis. Only those three albums for one whole year. I know every note and I got completely bored. For this exhibition I only listened to audio books. A lot of Moby Dick, two books on the history of the CIA and academic texts on the phenomenon of secrecy and how states regard their secrets. I like this feeling of secrecy and I think there is a lot of secrecy in these paintings as well. I guess some of the brushstroke’s freedom is influenced by Jazz and some of the subtext might come from listening to these books about the CIA.

AW: That’s very theatrical.

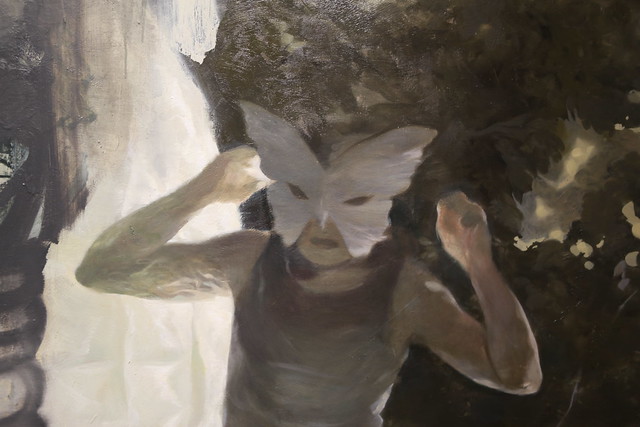

LE: It is. I try to stage things. Making a stage with interesting props and elements and then chase the characters into that stage – freeze-frame them a while. You know it’s interesting when you think about what’s happing in Japan right now: ‘Oppenheimer’s Garden’ shows J. Robert Oppenheimer jumping in the front – that was a snapshot from his lectures – and car wracks in the background. I thought about a sort of vegetation while painting it. But now the newspapers are full with those images of broken landscapes. Hence the title: Oppenheimer’s garden – the combination is interesting, with ‘garden’ as something peaceful and Oppenheimer’s work being the opposite.

AW: Is this person in back of your work ‘Mother’s day’ committing suicide?

LE: No, it’s rather like an S&M thing – she is tied up.

AW: So she is still alive?

LE: I hope so.

AW: You juxtapose quite opposing and extreme elements in your paintings ‘Mother’s Day’.

LE: (laughs) It could be like a bizarre birthday party from hell. I like to insert little enigmas and puzzles into each painting, pointing to something where it’s hard to guess the context. For instance, a sign like the Saint Andrew’s cross, with the magpie in the corner. I got that magpie from Goya’s portrait of the son of the conde de Altamira - that little boy in the red suit. Especially early renaissance art always had these little codes and secrets, and I am sure that in their time they were readable. We still have the keys nowadays, but we don’t have the doors anymore. The stories are lost, but the signs are still left there.

AW: You really do have a lot of art historical references and signs in your paintings.

LE: I do. If you go to the Prado in Madrid and you look at six or seven of the major Velazquez paintings, you’d be confident by that. You would see that this work travels through time, that it’s very accessible, very vibrant, very demanding. You would have the same experience with works by Jackson Pollock or Francis Bacon. You would be very relieved that art actually exists – that it’s not contrived. It was there, long before theory. I have been obsessed with Diego Velazquez, German art from the 1980’s, the American abstract expressionists, like Jackson Pollock; and of course the British, like Francis Bacon. But now I am only looking at really old art, like 16th century painting. I used to think of those as antiques and didn’t see their relevance. But it was just a question of maturity, I can see that clearly now.

AW: From where do you get your images?

LE: Some are my own family snapshots – but I mix it with everything. I am really just looking for an interesting composition, or a juxtaposition that doesn’t seem contrived, because my paintings are not collages. Its not footage on painting, rather it has to look natural. I also want the paint to show and I want it to be clear that it is just paint. One shouldn’t make the mistake of confusing the image with reality. You have to remember that it’s a fiction.

AW: How is your view on reality then? Do you try to avoid it in your works?

LE: I believe that fiction is very close to reality. Reality is a very dodgy word. Reality is very evasive – you don’t see it. I am not keen on documenting what I see in contemporary life. Everything in my paintings comes out of an experience – everything means something – but it has changed on the way. I have always preferred good storytellers, who would speak in a subdued voice that makes me lean back and listen to it. If art’s assignment is to reflect society, then you could only reflect the hubbub and the noise. If you bring all that noise into the gallery then you have only mirrored things. It’s very hard to see that as art. It’s so much more interesting to try showing some kind of excellence instead of showing that life is shit. That’s such a banal truth – if it’s a truth at all.

AW: Why do you blur your character’s faces?

LE: That has to do with clichés again. A lot of cliché lies in the portrait. It grabs the eye right away. I think when you can leave out the face you can be very articulate about an arm or a hand instead. Giving them equal importance, I can avoid the cliché of painting someone who looks sad perhaps, or happy. It’s a way of confusing the issue. But there are accurately painted faces behind each blurred face. I first paint it and then break it down.

AW: Why do you do that?

LE: It’s an interesting painterly process. It’s fun to paint accurately, but I don’t like the result.

AW: Would you say that your paintings have changed a lot in the past ten years?

LE: I think I am leaving some painterly flourishes behind for the sake of clarity. Some of the painterly tricks that I have used I got tired of – I think of them as clichés now. Some brushstrokes are more clichés than they are paint. I am trying to get close to the core of things.

AW: Did the compositions change?

LE: I think my compositions are very classical. They have the diagonals, the way they are compartmentalized. I have always been obsessed with compositions, but the colour had to work along with it. It took me quite a while to make colour speak with its own voice.

AW: Each of your paintings seems to me like a little novel.

LE: Yeah, I think of my each painting as a one-act play.

AW: Is it important for you that your paintings are beautiful?

LE: It is. I think it would be a big problem if they were pretty. If you want to trick someone getting into this universe of a picture you have to, as David Lynch does it, make it really attractive. I like the combination of what pleases the eye and what repels the eye. Or maybe pleases the eye and repels the mind.

AW: This is quite extreme in your work ‘Broken landscape,’ isn't it? The scene happening in the front of the painting looks like a rape.

LE: It looks like a rape but it’s not. It’s actually a physician instructing a policewoman how to revive a victim after drowning. It’s from an instructional film about how you do that. But once you freeze-frame it, it looks like someone is being attacked. I thought that was funny. And the juxtaposition with this broken landscape in the back – the bay of Naples – and this ridiculous activity of golf. This is how we live – the world is burning and we play golf.

AW: Do you have a favourite picture in this exhibition?

LE: It changes all the time. It’s probably ‘Oppenheimer’s Garden’ and ‘Mother’s Day’. I started on ‘Mother’s Day’ very early and that was very encouraging for me. Because usually the stuff to begin with is all crap and a few months before the exhibition the good work starts coming. But I could comfort myself with that one.

AW: How long time do you need for one painting?

LE: For instance ‘What game shall we play’ took me seven weeks. I like that one now, but I used to hate it. I thought it was too busy – too much going on – it seemed really contrived. The title is based on an old song by Chick Chorea.

AW: How important are titles for you?

LE: The title can be a sign, or a pointer. At other times it can be confusing, make the viewer stumble. I like titles – they all mean something. It gives you something more to do, something more to think about. The title for the painting ‘Director’s Cut,’ for example, refers to the first FBI director John Edgar Hoover, who is quite off the screen. He monitored the secret life of every important American, like John F. Kennedy, or Nixon for 35 years. Everything is on tape in the FBI archives. But they have this ‘Espionage Act of 1917’ – so after 30 years they let it all go. Now you can read everything. You can tell when people have been lying.

AW: The composition of this painting seems very non-classical to me.

LE: True, it’s very non-classic. It does have some classic elements though – linked to Fragonard.

AW: In this show you exhibit two Fragonard studies. Do you often paint studies of old masterpieces?

LE: Well, I have been doing it for a while. I made some studies of Vemeer and of Velazquez. It’s kind of comforting and it usually doesn’t become a painting that I show; it rather becomes a training exercise. Sometimes it can go a little beyond that, like an interpretation.

AW: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

LE: I would definitely be a painter. And I hope that my work travels well; that I can show in different spaces and that I would have a dedicated audience. Most of all, I hope that the work itself evolves.

AW: Where would you like to see your work the most, country-wise?

LE: Berlin would be great.

AW: Is it important for you that your paintings are beautiful?

LE: It is. I think it would be a big problem if they were pretty. If you want to trick someone getting into this universe of a picture you have to, as David Lynch does it, make it really attractive. I like the combination of what pleases the eye and what repels the eye. Or maybe pleases the eye and repels the mind.

AW: This is quite extreme in your work ‘Broken landscape,’ isn't it? The scene happening in the front of the painting looks like a rape.

LE: It looks like a rape but it’s not. It’s actually a physician instructing a policewoman how to revive a victim after drowning. It’s from an instructional film about how you do that. But once you freeze-frame it, it looks like someone is being attacked. I thought that was funny. And the juxtaposition with this broken landscape in the back – the bay of Naples – and this ridiculous activity of golf. This is how we live – the world is burning and we play golf.

AW: Do you have a favourite picture in this exhibition?

LE: It changes all the time. It’s probably ‘Oppenheimer’s Garden’ and ‘Mother’s Day’. I started on ‘Mother’s Day’ very early and that was very encouraging for me. Because usually the stuff to begin with is all crap and a few months before the exhibition the good work starts coming. But I could comfort myself with that one.

AW: How long time do you need for one painting?

LE: For instance ‘What game shall we play’ took me seven weeks. I like that one now, but I used to hate it. I thought it was too busy – too much going on – it seemed really contrived. The title is based on an old song by Chick Chorea.

AW: How important are titles for you?

LE: The title can be a sign, or a pointer. At other times it can be confusing, make the viewer stumble. I like titles – they all mean something. It gives you something more to do, something more to think about. The title for the painting ‘Director’s Cut,’ for example, refers to the first FBI director John Edgar Hoover, who is quite off the screen. He monitored the secret life of every important American, like John F. Kennedy, or Nixon for 35 years. Everything is on tape in the FBI archives. But they have this ‘Espionage Act of 1917’ – so after 30 years they let it all go. Now you can read everything. You can tell when people have been lying.

AW: The composition of this painting seems very non-classical to me.

LE: True, it’s very non-classic. It does have some classic elements though – linked to Fragonard.

AW: In this show you exhibit two Fragonard studies. Do you often paint studies of old masterpieces?

LE: Well, I have been doing it for a while. I made some studies of Vemeer and of Velazquez. It’s kind of comforting and it usually doesn’t become a painting that I show; it rather becomes a training exercise. Sometimes it can go a little beyond that, like an interpretation.

AW: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

LE: I would definitely be a painter. And I hope that my work travels well; that I can show in different spaces and that I would have a dedicated audience. Most of all, I hope that the work itself evolves.

AW: Where would you like to see your work the most, country-wise?

LE: Berlin would be great.

www.larselling.no

Interview and text by Anna-Lena Werner

Photography by Lars Bjerre

LARS ELLING 'OPPENHEIMER'S GARDEN'

16th of March - 28th of April 2011

Thomas Williams Fine Art Ltd.

22 Old Bond Street

W1S 4PY, London

Open from: Monday-Friday, 10am-6pm